In the opening pages of her stunning and brutal new book, “The Last of Her: A Forensic Memoir,” Kim Dana Kupperman recounts the 19-page suicide note her mother, Dolores Buxton, left in 1989. It cataloged, among other things, instructions for the renovation of her Manhattan apartment, the marketing of her makeup line, and which lie to tell which attorney. This last bit of subterfuge was the toxic thread that her mother wove through a lifetime of scams and schemes, drug addiction and abuse.

Buried among the mountain of particulars were a mere five lines directed to the book’s author, who was Buxton’s sole daughter and next of kin, apologizing for the situation.

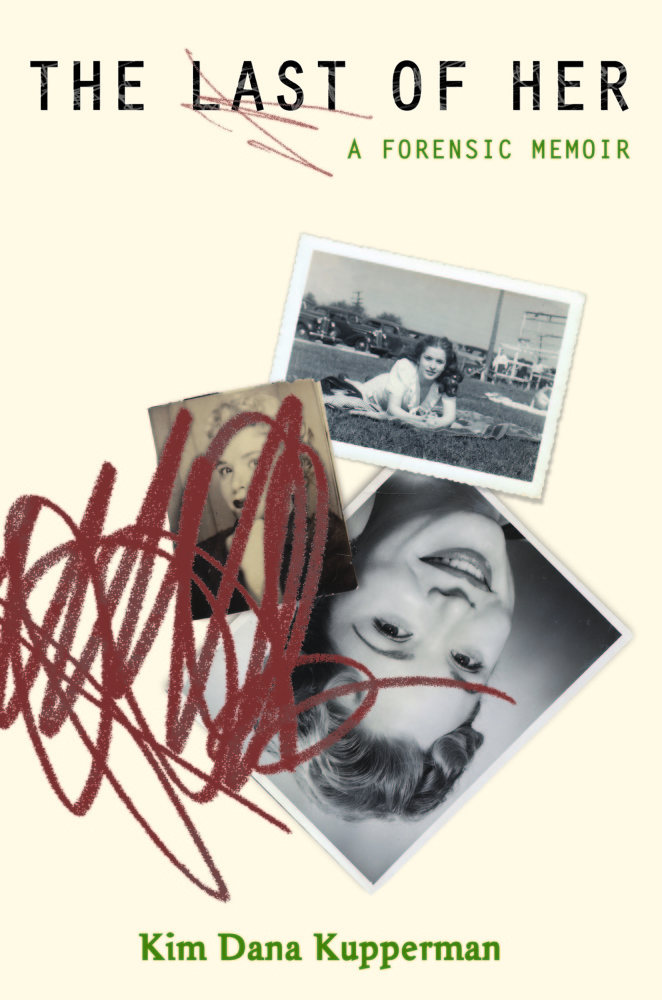

So begins Kupperman’s inquiry into her mother’s life and unraveling, and their complicated mother-daughter relationship. Kupperman has written a book that is variously a detective story, noir tale and courtroom drama. That the principal player was a head-turning beauty and diva adds color to a story that’s already replete with cinematic detail.

Buxton was almost 60 when she took her life. Chronic pain from spina bifida, subsequent surgeries and eventual drug addiction were among the reasons for her steady decline.

The author, then 31, had severed ties with her mother two months before the suicide, on the advice of an attorney. Over the years, Dolores committed crimes both large and small. In 1958, she was indicted for assaulting a pregnant woman with a hammer. The woman in question was the wife of a former lover. More recently, she had engaged in insurance fraud, imploring her daughter to lie under oath on her behalf. (Kupperman refused.)

Dolores was also an identity thief, renting out the back room of her apartment to tenants whose Social Security numbers she would then steal. At the time of her death, she had amassed eight Social Security cards with different names, plus three passports. Significantly, the passports all featured Dolores in various disguises, differently coiffed and made-up. One of the phony passports was put in Kupperman’s name.

“I recalled the feeling that I might wake up one morning with my identity erased, trapped as a pretend character my mother wanted me to play in her real-life dramas,” Kupperman says. Then later: “It didn’t occur to me that Dolores’ need to shape identity – by theft, with lies, through a variety of invented narratives – was her vocation.”

Among her many fictions was the notion that Dolores was fit for parenting. In an epic court battle, however, she lost custody of her daughter to her ex-husband, who was a compulsive gambler and womanizer. Soon after, the young Kupperman, a scrawny, troubled child who had stopped up the toilets in school and set a fire under her bed, became a visitor in her mother’s home and a tool of her ongoing exploits.

Kupperman’s challenge in this memoir was to exhume her mother’s history and to make sense of the person Dolores became. To that end, she unearthed all manner of legal documents, records and files. Not surprisingly, she found that history repeats itself, sometimes with only slight variation.

Dolores’ father, “Buxie,” was a swindler and con man who used his daughter as a shill in his own schemes. Further, a long line of abandonment preceded Dolores, going back several generations. Which raises the specter of inevitability, a question that looms throughout the book.

How did the author survive the seemingly endless, often jaw-dropping, perils of her upbringing and not devolve into a lowlife herself?

“All I can offer is this tidbit of wisdom from people who work with child victims of violence,” she says. “Resilience depends on books in the home and the presence of at least one caring adult.”

Indeed books and writing were the author’s balm from an early age. By 10, she had discovered that writing could be a form of liberation and a conduit to oneself. “Narratives are always saving us,” she notes, keenly aware that she also inherited the storytelling gene that wreaked havoc before her.

Fortunately for the author and her subsequent readers, Kupperman would go on to become an award-winning writer and teacher, who founded Welcome Table Press, a nonprofit dedicated to the essay, from her Down East Maine home.

Long before the word “post-truth” entered the parlance, Kupperman was waging war against lies and disinformation on her home turf. Not only does her story evoke the collateral damage of suicide, nearly 30 years after the fact. At bottom, this lyrical, probing memoir suggests that knowledge is rarely sufficient and reconciliation is an inside job.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews. Her work has appeared in The Christian Science Monitor, Chicago Tribune and Dallas Morning News.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.