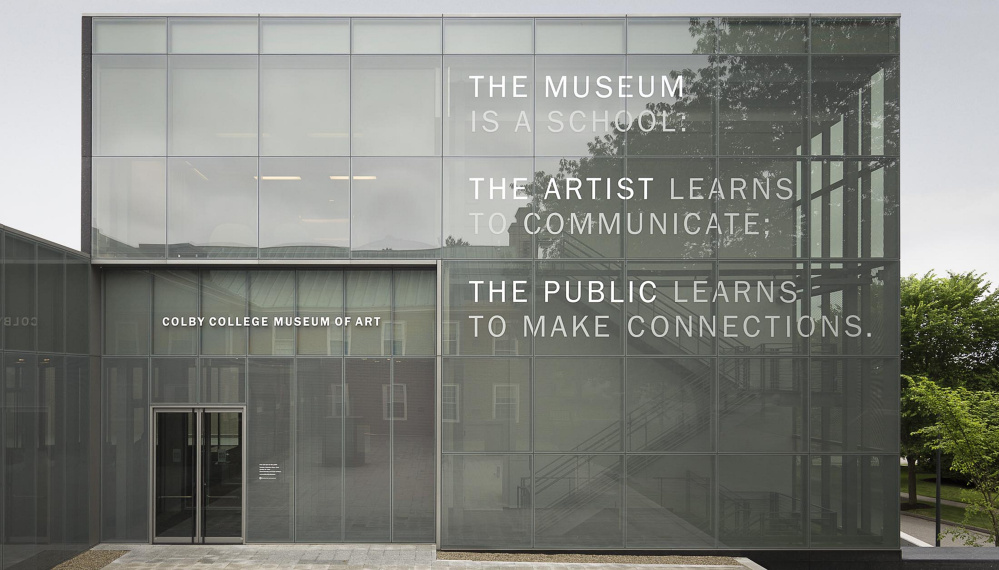

The two buildings Frederick Fisher designed for the Colby College Museum of Art are both among Maine’s best structures: the colonial-minimalist Georgian gem of the Lunder Wing and the sleek, glass-curtain-walled Alfond-Lunder Family Pavilion. Only one thing about this latter building that bothers me: The huge-lettered quote by Luis Camnitzer chiseled into the window over the entry yard that shouts: “THE MUSEUM IS A SCHOOL. THE ARTIST LEARNS TO COMMUNICATE. THE PUBLIC LEARNS TO MAKE CONNECTIONS.”

A college museum as a school: That’s fine. It’s a bit condescending to act like the museum is where the public learns to make connections – as though the public didn’t know why they went to the museum until they got there. But if you mentally change “public” to “student body,” it’s not so bad. But the idea that a museum (typically not an emerging artist launch pad) is the vehicle by which the artist learns to communicate is just weird. Most of the artists on view at the museum, after all, didn’t learn to do what they do at a museum. And is that actually the mission of a museum – to teach artists? Or is the mission to display, study and safely house worthy work in perpetuity?

This phrase seems intentionally buried between two less inconvenient statements, neither premise nor punctuation. But while it had first struck me as a morally corrupt pronouncement, I now think there’s more to it when you consider it in light of the museum’s status as a cultural leader.

First, let’s remember that the Colby College Museum of Art is not only Maine’s biggest and best museum but it is top among the most significant and largest college art museums in the United States. Secondly, we need to consider that Colby’s cultural conversations aren’t primarily local, but from the head of the class. Colby’s cultural peers comprise the international academic community. When we switch gears from seeing Colby as one of Maine’s many art venues to considering it in light of its cultural leadership role, we should expect some chiseled heft in it mission pronouncements. The building about which we’re talking, after all, happened under former Colby president William Adams, who left in 2014 to become President Obama’s director of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Because culture plays a bigger role in shaping our values and critical abilities in a democracy, cultural leadership is fundamentally important in a republic. Culture in a despotic state can only be propaganda or kitsch, since what it only truly reveals are the shape of the hegemonic filters. But in a free state, culture can reflect who we are and what we believe. In America, art is our moral mirror, our societal selfie.

Because we don’t have an infrastructure of intellectuals like, say, France, we look to our artists. Because of our market orientation, Americans tend to look at the “most successful” artists, and so “Hollywood” has become the opponent-created stand-in term for the societal heft of leading American culture-makers, but among them we should include writers like Stephen King and Dave Eggers, musicians like Madonna and David Byrne and – in the world of Governor Schwarzenegger, Governor Ventura, Senator Franken and President-elect Trump – television personalities.

The most obvious quality of Fisher’s Alfond Lunder Pavilion is the street-facing glass wall facade with the giant Sol Lewitt wall mural that glows at night with an art presence beyond anything else in the state. The best part of the building, however, is the foyer. With stylish couches and cafe tables, it’s a warm, low-barrier welcome mat for the public. But it’s also arguably the best art space in Maine.

Colby’s leading exhibition now is more interactive than didactic. In some ways, it’s the opposite of what we expect from art: Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander has taken pages from comic novels and removed the images and the statements. What is left are dozens of comic image blocks with empty dialogue and thought bubbles painted on the walls of the museum foyer. Neuenschwander has provided chalk for the visitors to fill in the images and dialogue themselves.

The denuded comics originally depicted Zé Carioca, a gruff, rascally, soccer fanatic of a cigar-smoking jitterbird who has been no less of a sensation in Brazil than Charlie Brown has been in America. So what does it mean for an artist to turn the canvas and brushes over to the audience? Neuenschwander has the spotlight in one of America’s leading museums and yet chooses to turn the stage over to the visitors. That is a statement.

Just a few feet away is a group of artist Barbara Gallucci’s artificial-turf colored bean bag chairs – literally on pedestals, but probably only more fun and welcoming nonetheless. The challenge to the audience is the dare to dissolve the imaged barrier, the fourth wall of art. While the private collection of weathervanes and installation of highlights from Colby’s folk art collection just came down from the nearby changing exhibition galleries, they represent one aspect of what we can typically see at Colby: folk art objects from our practical past. Weathervanes, quilts and fire screens were arts and crafts objects found at typical homes and they were interactive art objects.

From an institutional standpoint, Colby’s messaging seems clearly geared toward empowering the public. Art is who we are, it whispers. It represents our needs, our priorities, our values.

Authentic cultural leadership requires vision and the courage to take a risk in doing what is right. Anyone with money in America can put forth propaganda. And there is a fine line between propagandandistic kitsch and art: Michelangelo, after all, was forced against his will by Pope Julius to paint the Sistine Chapel – and within strictly filtered guidelines. But, unlike Michelangelo, we live in a republic whose society has valued individual freedom over institutional ideologies.

What I don’t like about the “MUSEUM IS A SCHOOL” pronouncement is mostly the propagandistic tone with its sense of close-minded ideological blinders. But what I see inside of Maine’s leading art institution inspires moral clarity, a fully American sense of righteousness with open eyes to our communities, our past and our world. If you want to see cultural leadership in action, go to the Colby College Museum of Art: It’s free for everyone.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at dankany@gmail.com.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.