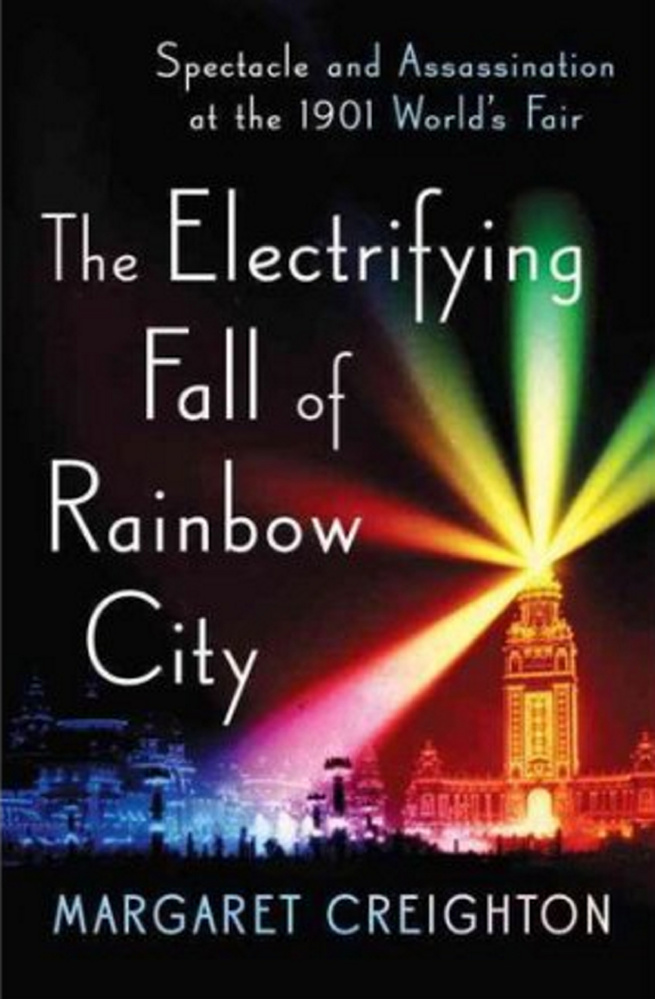

Bates College professor Margaret Creighton continues to prove herself among Maine’s most stalwart historians, with the appearance of “The Electrifying Fall of Rainbow City: Spectacle and Assassination at the 1901 World’s Fair.”

Creighton’s previous volumes, including “Rites & Passages: The Experience of American Whaling” (1995) and “Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History” (2005), were fun to read, fact-packed and full of fresh ways of interpreting events. The author’s fans will not be surprised, then, by a delightful read and an amazing juxtaposition of revelations throughout “The Electrifying Fall.”

In common with the earlier volumes, this one does not focus on Maine, but neatly references our state in context. We learn, for instance, “In Old Town, Maine, nearly half the population was packing its bags” for Buffalo, New York, in 1901, along with impressive contingents throughout the Western Hemisphere.

That’s because the city, then the eighth largest in the United States, was hosting the World’s Fair. This was the age before radio, television and homogeneous entertainment in America’s small towns. World fairs were the in thing and Buffalo was a commercial nexus, with its canals, connection to Canada, and growing steel production powered by the mighty Niagara Falls.

Buffalo’s community leaders, almost exclusively prosperous white males, were proud and anxious to push their city higher in the economic pecking order. America had just won the Spanish-American War, and the astonishing 20th century was on the quick march. Raising funds for such an extravaganza required energy, planning, the appearance of President William McKinley and anything else that could be pulled out of imagination’s star-spangled hat.

What might have proved a garbled stack of events in the hands of a lesser writer springs to bright and understandable life in the words and design of Creighton. Her tour of the World’s Fair is formed by official records, newspaper accounts, a deep knowledge of life and culture, and, most delightfully, by the scrapbook accounts of a young city school teacher, Mabel E. Barnes (1877-1946), who visited the fair 33 times and took exacting notes. Barnes had a grand time during her summer vacation and left an unrivaled description and framework, now in the Buffalo History Museum archives.

Still, even Barnes’ inquiring eyes and mind did not see everything. The American Negro exhibit was billeted on the edges of the midway and, in spite of leading African-American activist Mary Talbert’s effort to promote the notion of progress, the fair promoter chose to spotlight “Darkest Africa and Old Plantations Shows” with “specimens of pygmies and cannibals.” This is what the general public was given and perhaps wanted.

At Talbert’s pavilion, which featured the achievements of Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Dubois and others, the New York Times wrote blandly, “We may as well be entirely frank in the appraisal. Much of it is rubbish. None of it is very great.” In retrospect, one might say visitors, promoters and the press missed the forest for the trees.

They could not miss one tragic event, however, that occurred on Sept. 6, when an obscure assassin shot President McKinley at the Temple of Music. Saved from an additional bullet by quick-thinking James Parker, an African-American standing in line who wrestled the gunman down. McKinley remained upright saying, “Go easy on him.”

It seemed that McKinley would survive, for a short while, in the care of Buffalo’s top physicians, but he died eight days later, ushering in the whirlwind era and the iconic new leader, Theodore Roosevelt. In quick order, the murderer, Leon Czolgosz, whose name the public never learned to pronounce correctly, was tried, convicted and electrocuted.

During this time, the redoubtable middle-aged Annie Edson Taylor became the first person to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel and survive. And there were the ongoing antics of Frank “The Animal King” Bostock, who sought to keep his star performer, “Chiquita, the World’s Smallest Woman,” from running off with her true love, then planned to electrocute the rogue elephant “Jumbo II.” And so went the magical mystery tour.

Anyone who thinks history is dull or useless owes it to themselves, and the rest of us, to read “The Electrifying Fall of Rainbow City.”

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He lives in Portland with his wife, Debra.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.