PARIS — Ever since Donald Trump proved last November that anything is possible in the topsy-turvy new world of Western politics, May 7 has been circled on European calendars with a mix of giddy anticipation and existential dread.

To right-wing populists, the presidential election in France – a country scarred by unemployment and terrorism – seemed to offer the next big opportunity to remake the postwar global order in their own nationalist, nativist and protectionist image.

To the mainstream, it looked like a possible third strike after Trump and Brexit – one with the potential to doom the European Union, NATO and other pillars of the trans–Atlantic alliance.

But as tens of millions of French voters prepare to cast ballots Sunday, indicators suggest that the populist wave is likely to bypass Gallic shores.

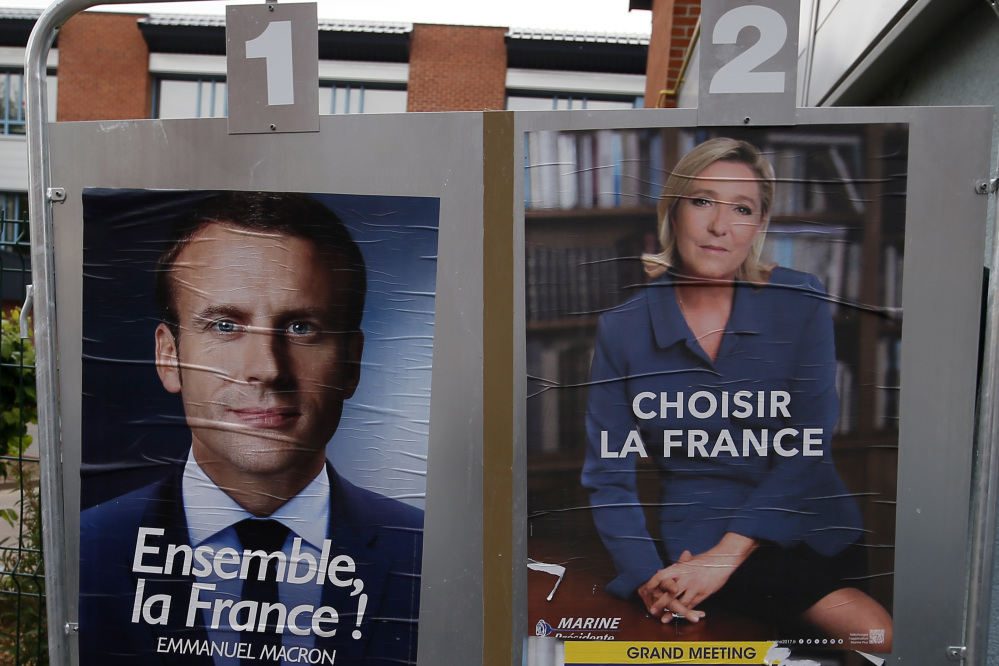

In final pre-election polling, independent centrist Emmanuel Macron held an overwhelming advantage of around 25 points over far–right challenger Marine Le Pen – up from 20 points days earlier. Even with the last-minute release of thousands of hacked Macron campaign documents, analysts said the scale of his lead gave Le Pen little hope of eking out a victory.

‘Chances are very weak’

“Her chances are very weak,” said Olivier Rouquan, a political analyst at Pantheon-Assas II University.

A Le Pen loss, however, will hardly be a knockout blow for populism – or a ringing vindication of the establishment.

If anything, the French campaign has solidified the new fracture lines in modern politics, which bear little relation to the relatively modest differences marking the old left-right divide. Instead, the choice voters face on Sunday illustrates the profound new chasm in the West: between those who favor open, globalized societies and others who prefer closed, nationalized ones.

“What’s the common ground between Macron and Le Pen? There is none. What we’re seeing is historic: a choice between two completely different modes of organizing a society,” said Madani Cheurfa, a professor of politics at Paris’s Sciences Po. “The world is focused on France because France has managed to encapsulate – almost to the point of caricature – the debate underway across the world.”

Already knocked out of the presidential race are the two mainstream parties, the Socialists and the Republicans, which have led France for much of its recent history. Both allowed their messages to get muddled and strained as they attempted to straddle the new divide.

The candidates who are left are unapologetic champions of their respective camps. They rarely try to reach across to those in the other. Their supporters see the world in ways that often seem diametrically opposed.

Dismantling the EU

Macron, a 39–year–old former banker and economy minister, celebrates immigration as a cultural and economic force for good. Flags with the EU’s blue field and gold stars are a common sight at his rallies, and he enthusiastically endorses the bloc as the continent’s best guarantor of peace. His supporters tend to be educated, urban and optimistic.

Le Pen, the 48-year-old leader of a far-right party that her father founded in the 1970s, rails against the evils of mass immigration and warns that France is losing its identity amid a tide of mostly Muslim newcomers. She has called for the dismantling of the EU, threatened to take France out of NATO and heaped praise on Russian President Vladimir Putin. Her backers tend to be rural, white, less educated and, without a radical shift in direction, gloomy about France’s future.

Until recently, the option embodied by Le Pen wasn’t even on the ballot for votes like the one Sunday. When it was – her father, convicted Holocaust denier Jean-Marie Le Pen, made the final round of the French presidential vote in 2002 – it was defeated by a massive margin.

But Marine Le Pen has kept this year’s contest reasonably competitive until its final days, and is on track to more than double her father’s vote share from 15 years ago.

That trend explains why, even if Macron claims the presidency on Sunday, his supporters say they will be more relieved than exultant.

“If we win, we have five years to do something with it,” said Aurélie Quartier, a former elementary school teacher who was handing out Macron fliers near a subway stop in a working–class neighborhood of eastern Paris this past week. “Otherwise Le Pen will be elected in the first round in 2022.”

Quartier, 38, said she had never been involved in politics until this year, when she realized that Le Pen’s National Front could actually take hold of the Élysee Palace. The thought chilled her, and galvanized her.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.