The yearlong Canterbury, N.H., project aimed to make sure all the town’s vets are remembered.

CONCORD, N.H. — A New Hampshire town has finished a yearlong project among its 34 cemeteries to identify the graves of its military veterans – from the pre-Revolutionary War era to Vietnam.

Canterbury is one of at least several towns that have taken on such a project in recent years, using cemeteries to learn about local history and to make sure those in the military are remembered. Gilmanton and Bow also have been identifying veterans’ graves.

John Goegel, a cemetery trustee in Canterbury, said the town has identified 122 veterans.

The Revolutionary War-era ones include six brothers: one who served under Gen. Benedict Arnold before Arnold defected to the British, and another who was a slave given his freedom and land after the war.

American flags usually are placed at veterans’ gravesites. But for Goegel and other researchers, that caused some confusion. Some veterans’ graves had flags; some didn’t. And some non-veterans’ graves had flags.

“Some people just put flags out for their loved ones, not knowing that there’s a certain connection between a flag and a cemetery and military service. That was one of our problems,” he said.

The cemetery trustees’ research referenced local sources, such as James Lyford’s “History of Canterbury,” and the “History of the Twelfth Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion.”

Their research shows that one veteran, Asa Foster, who died in 1861 at age 96, enlisted in the Continental Army on July 4, 1780, at age 15. He was sent to West Point, New York, under Arnold’s command and was one of his bodyguards before Arnold defected to the British. Another veteran, Sampson Battis, a slave living in Canterbury, was freed and received 100 acres from his owner after his Revolutionary War service.

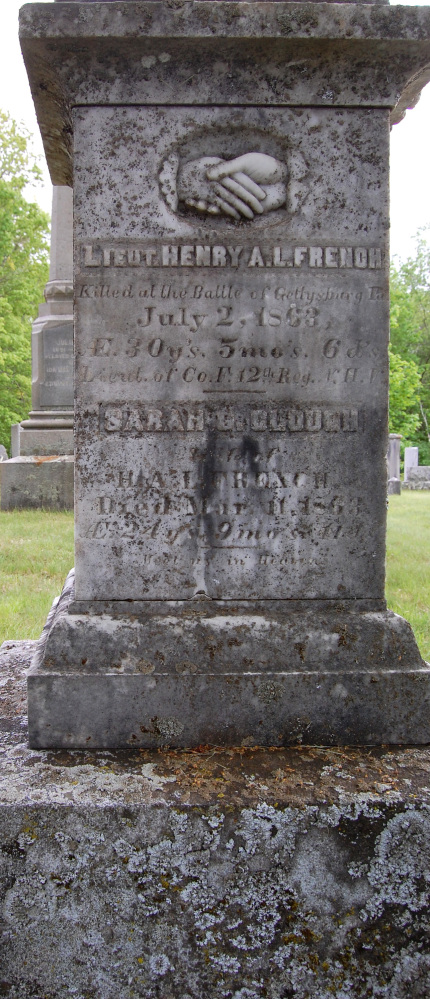

Goegel said some of Canterbury’s veterans died in their military service and that while the government issued headstones placed in the town’s cemeteries, the bodies of Civil War combatants, for example, may have been buried on the battlefields. One of them, Lt. Henry French, was killed July 2, 1863, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, nine months after the birth of his only child and four months after the death of his wife.

In Gilmanton, the American Legion Auxiliary Ellis-Geddes-Levitt Unit No. 102 published a book about its 365 veterans. The oldest on record died in 1778. Evelyn Sanville, the group’s historian, said her main obstacle was in finding all of the 34 cemeteries and burial grounds.

“Many are family cemeteries that long ago were closed,” she said. “Many are only accessible by foot or over private property. … There are at least two that I have yet to visit personally because I don’t know exactly where they are.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.