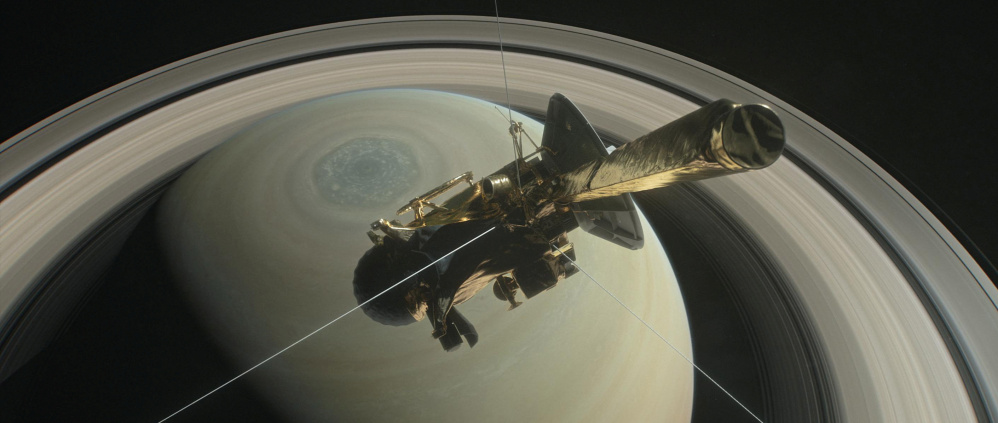

LOS ANGELES — After 13 years of observing Saturn, its rings and its myriad moons, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is less than three weeks away from a fiery, brutal end.

Early in the morning on Sept. 15 the aging spacecraft will hurl itself into Saturn’s atmosphere at speeds of more than 75,000 mph.

It’s a deliberate death plunge from which it has no hope of returning.

Within three minutes of diving into Saturn’s tenuous upper layers, the two-story-tall spacecraft will be torn apart.

Then it will melt.

Then it will vaporize.

In the end, Cassini will become part of the very planet it has studied for more than a decade.

“I like to say it’s going out in a blaze of glory,” said Linda Spilker of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Canada Flintridge, the project scientist for the mission. “It will be trailblazing until the very last second.”

Earth-bound astronomers will keep a close eye on the planet at the moment of Cassini’s death to see whether they can detect a small flare as the spacecraft burns up like a meteor in the Saturnian sky.

But they don’t expect to see much.

“The mass of Cassini is so small compared to the mass of the planet,” Spilker said. “And the plunge is happening on Saturn’s day side.”

She added that there is no fear that Cassini’s death dive will contaminate the ringed giant. Molecules from the spacecraft will quickly spread out across the planet, which is big enough to hold more than 700 Earths.

Still, Cassini’s suicide mission is not all gloom and doom. The spacecraft will venture deeper into Saturn’s atmosphere than ever before, collecting new data and beaming it back to Earth up until the last seconds of its life.

“We are reconfiguring the spacecraft and turning Cassini into an atmospheric probe,” said Earl Maize, the mission’s program manager, who also works at JPL.

Cassini could make it as far as 120 miles into the Saturnian atmosphere before all its instruments cease to function, mission engineers said.

“I find great comfort that Cassini will continue teaching us until the very last second on Sept. 15,” said Curt Niebur, Cassini program scientist based at NASA’s headquarters in Washington.

The flagship mission launched in 1997 and entered the Saturnian system in 2004.

Over the last 13 years it has discovered plumes of water ice on the moon Enceladus, confirmed the presence of methane and ethane lakes and rivers on Titan, watched the seasons change on Saturn, discovered six new moons and revealed complexities in the planet’s rings that had never been seen before.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.