The original Maine Mariners made their debut the same year – 1977 – as a movie about minor-league hockey called “Slap Shot.”

A raunchy comedy lampooning the notion of violence as entertainment, the film became a cult classic and left an impression that, at least in the lower levels of professional hockey, fists mattered more than finesse.

You remember that old Rodney Dangerfield one-liner: “I went to a fight the other night and a hockey game broke out.”

Is that still true? Was it ever the case?

Portland is a year away from the return of pro hockey, in the form of an ECHL franchise. Also named the Maine Mariners, the ECHL club will fill the void left at Cross Insurance Arena by the 2016 departure of the Portland Pirates, an American Hockey League club now renamed and operating in Springfield, Massachusetts.

So will dropping down a level in hockey’s minors mean the Mariners 2.0 will be dropping their gloves more than their predecessors?

One former Pirates executive thinks so.

“Portland fans will see a little more fighting at the ECHL level,” predicted Brian Petrovek, former chief executive officer of the Pirates who now holds that same title with the Calgary Flames’ AHL affiliate in Stockton, California. “Anecdotally, the ECHL still has more fighting at that level than at the American League level.”

Petrovek has seen both leagues up close. After leaving Maine in 2014, he assumed control of the Adirondack Flames in Glens Falls, New York. A year later, Adirondack dropped down one rung on the minor-league ladder, joining the ECHL as the Adirondack Thunder.

The numbers from Adirondack seem to contradict Petrovek’s perception, however.

According to hockeyfights.com, the Flames were involved in 70 fights in the 2014-15 season. The Thunder, with Petrovek continuing in his role as president, registered 50 fights in their first ECHL season and only 41 last winter.

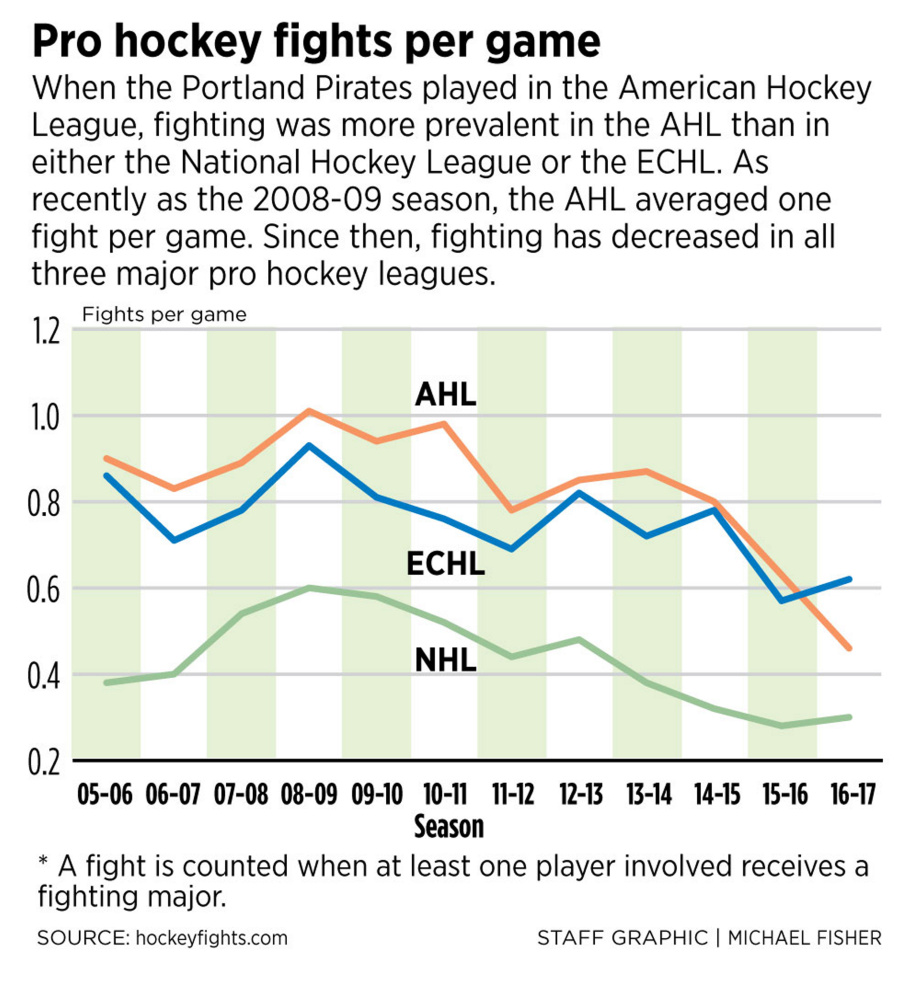

The notion that fighting is more prevalent in the lower levels of pro hockey than at the upper echelon has some truth to it. National Hockey League fights happen, on average, only once every four games. The AHL, as recently as 2009, had more fights than games. The ECHL, one step below the AHL, consistently lagged slightly behind – until last season.

In 2016, the AHL adopted new rules designed to curb fighting – automatic ejection for players who square off before or immediately after a faceoff, and a one-game suspension upon incurring a 10th fighting major during the season (and a suspension for each subsequent fight). The result? There were nearly 200 fewer fights last season. In six years, the AHL cut its brawls by more than 50 percent, from 1,178 to 509.

“They’re phasing us out,” said Trevor Gillies, the Pirates’ career leader in fights. Now 38, he still plays the role of enforcer, in his 19th season of pro hockey, for the South Carolina Stingrays of the ECHL.

“I think I’m the last of the dinosaurs,” he said. “I feel like it’s a shame for the other young tough guys out there.”

Fans in Portland voted Gillies their favorite Pirate when he played here from 2005-07, as much for his gentle demeanor in the community as for his tough-guy persona on the ice.

Similar rules have yet to be imposed in the ECHL, but Gillies can see the handwriting on the wall.

“I think it’s a shame what they’re trying to do to hockey, an absolute travesty,” said Gillies, speaking by phone from his offseason home in Augusta, Georgia. “I believe in a big brother mentality, a family atmosphere where we stick up for each other. I know Portland’s fans, and of course they like skill, but they like that hard-working, blue-collar hockey of banging bodies and energy. If you have a soft team in Portland and they’re not going to compete every night, (fans) are not going to support you.”

An examination of 12 years worth of data on fighting in pro hockey (compiled by hockeyfights.com) revealed Portland as a place where fisticuffs were slightly more common than in the rest of the AHL. The Pirates averaged 0.94 fights per game in their 427 home dates since 2005. Over the same period, the entire AHL averaged 0.83 fights per game in 13,636 contests.

Contrary to the perception of the ECHL as more of a fighting league, the average at the lower level was 0.75 fights per game for the 12-year period. Only in the 2016-17 season did fighting in the ECHL (0.62 per game) surpass that of the AHL (0.46).

“I think to the average person, they remember the cartoonish ECHL, which was basically a bunch of thugs back when the AHL was a bunch of thugs,” said Andrew Hart of South Portland, a longtime Pirates fan. “But the days of Trevor Gillies-style players are long gone. Usually, people who are pretty prolific at fighting in the ECHL don’t tend to move up.”

Although fighting may be on the wane, it seems in no danger of disappearing.

“Next to a goal, it’s probably the one thing in hockey that does capture everyone’s attention,” Hart said. “Everybody likes to see a fight. Let’s be honest. In racing, everybody likes to see a crash. Anybody who would tell you different is being dishonest.”

Brian McKenna is commissioner of the ECHL, which formed in 1988 with five teams in four states but has grown into 27 teams in 21 states and one Canadian province. Sixty-six former ECHL players opened this season on NHL rosters, as did 40 coaches.

McKenna acknowledged a pugilistic bent to the ECHL’s early years, but said teams have focused much more on skill and finesse over the past decade.

“We only dress 16 skaters, so you don’t have the opportunity to have that extra one or two guys on your roster that are there simply for that purpose,” he said of the enforcer role. “If you’re in the lineup in the ECHL, you’re there to play, and play regular shifts.”

Danny Briere, vice president of hockey operations for the Mariners and a former Philadelphia Flyer, said the team is still building its front office and he hasn’t given much thought to its roster makeup.

“I don’t know the statistics, but if I look at junior hockey in Canada, the fighting is down,” he said. “In the American League, the fighting is down. My feeling is the ECHL will follow the same route.”

If it doesn’t, Briere said he will prepare for that as well.

“You look around the league,” he said. “If there’s a lot of fighting, you’ll want to protect your players. If there’s less fighting, you’re going to take that into account as well.”

Adam Goldberg, the Mariners’ vice president of business operations, worked in the front office of the AHL’s Hartford Wolfpack from 2006 to 2009.

“We had at least two fighters on the roster at all times,” he said. “It has been part of the game, and the history, but now that it’s starting to phase out, you see a lot more puck-handling skills and speed on the ice, and maybe some players who wouldn’t have survived in the ’70s and ’80s.”

Longtime observers of pro hockey in Portland understand the role of enforcers and instigators, of the need to protect highly skilled players from cheap shots. Such elements aren’t likely to disappear entirely.

“We’ll still see it,” said Kathy Hooper of Biddeford, “but I don’t think we’ll see more of it here.”

Scott Prue, also of Biddeford, said the main attraction remains the fast-paced, fluid action on the ice.

“Hockey is hockey,” he said. “The fighting is just an added bonus to get everybody riled up. I don’t look forward to it, but if we’re getting outscored and there’s not a lot to cheer for and a guy gets into a little scuffle with another player, then you get up and cheer.”

Glenn Jordan can be contacted at 791-6425 or

Twitter: GlennJordanPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.