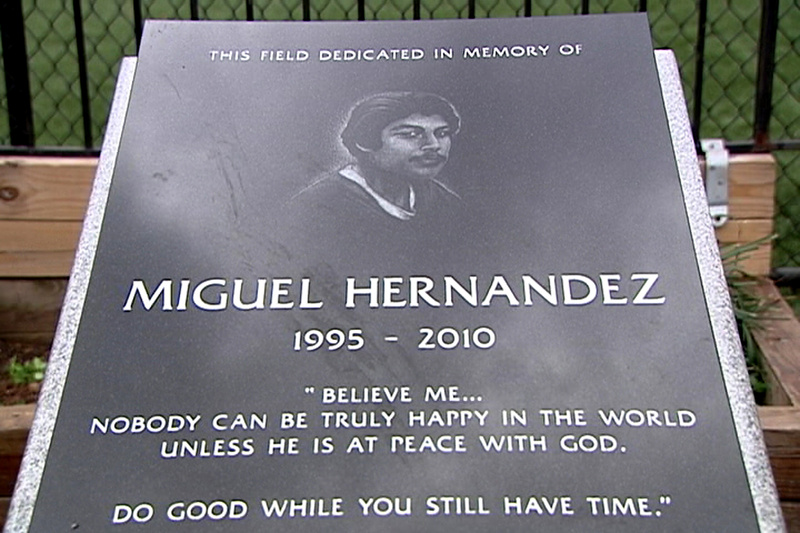

MANASSAS, Va. — Sitting a few steps away from a black marble memorial to his friend Mickey, who was stabbed to death two years ago at age 15, Ronald Ramos looks bewildered when asked why he didn’t take the SAT, seek financial aid and apply to college after graduating from high school.

“Parents don’t know what the system is here,” he says in an interview at Georgetown South, a Latino neighborhood in Manassas. “We don’t know what to do.”

Hispanics such as Ramos are the fastest-growing component of America’s work force. The country will need their taxes to help pay the Social Security benefits of retirees and their skills to fill jobs of baby boomers leaving the labor force.

Today, Ramos, who is 18 and of Mexican descent, is looking for temporary work to help pay for college. If he fails, he risks joining the more than 80 percent of Latinos ages 25 and older who don’t have a bachelor’s degree.

ONE IN 10 UNEMPLOYED

The lack of educational attainment among Hispanics is one of the biggest crises in the American labor force with far-reaching implications for the economy. Without more education, Hispanics won’t be able to fill higher-paying jobs, contributing to the already widening U.S. income disparity.

Without higher incomes, they won’t join the consumers that propel the earnings of U.S. companies ranging from Ford to Verizon Communications. The unemployment rate for Hispanics was 10 percent in October, compared with 7.9 percent nationally.

“You can’t meet our national goals and our work force needs without having a tactical plan for Latinos,” says Deborah Santiago, vice president of policy and research for Excelencia in Education, a Washington research organization that focuses on education of Hispanics. “This is just a factual statement given what the current population numbers are.”

Only 14 percent of Hispanics ages 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2011 compared with 51 percent for Asians, 20 percent for African-Americans and 34 percent for whites, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Hispanics were crucial to President Obama’s re-election Nov. 6, giving 71 percent of their votes to him according to an exit poll by Edison Research of Somerville, N.J., and published by The New York Times. They played a role in his victories in states including Florida, Colorado, Nevada and Virginia.

The president authorized a program in June that shields from deportation undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States before age 16 and are no older than 30 so they can attend U.S. schools or apply for work permits. By contrast, the Republican platform opposed amnesty for illegal immigrants, urged them to leave voluntarily and supported workplace verification systems.

Of the 47 million new workers entering the labor force between 2010 and 2050, a projected 37.6 million, or 80 percent, will be Hispanic, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics report in October. Their share of the work force will grow to 18.6 percent by 2020 and to 30 percent in 2050, doubling from 15 percent in 2010, according to the BLS.

That means by the end of the decade, about one in five available workers for companies such as Citigroup, Apple or General Motors will have last names like Ramos, Castillo or Perez.

Immigration trends could change. The net flow of immigrants from Mexico, the largest source of immigration to the U.S., began slowing five years ago, according to the Pew Hispanic Center in Washington.

ONE IN 10 UNEMPLOYED

Still, companies will count on growing Latino household formation to sell their products.

“If you don’t reach out to the Hispanic consumer, you cannot make it,” says Alvaro Cabal, Ford’s manager in charge of Hispanic communications, in Dallas. “From the iPhone to the Android, from cars to houses to sausages, that is the reality. It is going to be a huge population.”

Ford began to see the increase in Hispanic car buyers years ago and structured sales and marketing efforts toward them, he says. It’s paying off.

The Dearborn, Mich.-based automaker’s light-duty vehicle sales volume to Hispanics rose about 25 percent this year through June compared with a 9.7 percent increase in total sales, according to Polk, a Southfield, Mich., auto-marketing research company.

“This population represents the new America,” says Magda Yrizarry, chief talent and diversity officer at Verizon in New York. “Both as an employer, and as a company that is responsible to its shareholders, you have to be able to monitor and gain share” of both their spending and their talent.

Verizon recognized the importance of its Hispanic customers in the 1990s, Yrizarry says. Now, 11 percent of the company’s work force is Hispanic; it markets specifically to Latino consumers and trains its installation and in-store teams to work with them. It targets Hispanics who are proficient in Spanish and those who aren’t, rolling out an ad this year with Jennifer Lopez speaking English in one version and Spanish in another.

Yrizarry says Verizon needs a work force competent in science and engineering and is “concerned broadly” about technology acumen among U.S. students. Low college degree attainment by Hispanics limits the pool of candidates that the company can hire, she says. Verizon is a sponsor of the National Academy Foundation, which promotes industry-focused curricula at the high school level.

“In a growing economy, we will need extra workers,” says Richard Fry, a senior research associate at the Pew Hispanic Center. “And more than half of the new workers employers will work with will be Latino. Without a four-year college degree, they are going to have a difficult time in those upper-echelon managerial jobs.”

Fry’s research shows Hispanics making some gains. The number of 18- to 24-year-olds was a record 16.5 percent share of all college enrollments in 2011 compared with 11 percent in 2006. High-school completion rates reached 76 percent last year, also the highest on record. Associate degrees obtained by Hispanics rose to 112,211 in 2010, up from 97,921 the previous year and 51,563 in 2000, his research shows.

Yet a conversation with Ramos shows the numerous obstacles to getting through high school and into college. Before his friend Miguel “Mickey” Hernandez died of a stab wound to the chest in November 2010, gangs prowled the neighborhoods and their members were also in the schools, he says.

“You had to watch your back. It was really tough,” he says, adding that the violence now seems to have subsided.

OBSTACLES TO HIGHER EDUCATION

He says he lives in a house with seven other people. Finding a place to study was difficult. His brother is a drummer. His sister has two small children. His family doesn’t have Internet service, making his high school studies and any college application, financial aid and job-search process now difficult.

“There wasn’t enough money to pay for it,” Ramos says. “I would stay after school or go to the public library or to a friend’s house” to access class information online.

He didn’t know how to pay for college or even get transportation to attend, which is why he didn’t apply before graduating high school. He says he “never understood anything” about federal student financial-aid programs and the forms are confusing.

The wage benefits that come with higher education aren’t known by him or his friends, he says. Long-range planning and saving are difficult when his parents struggle to pay monthly bills.

“They just break their backs and get upset because they don’t have any money,” he says. His mother is a homemaker, and his father works for a construction company.

Now a few months out of high school, he says his dream is to spend two years at a community college then transfer to a four-year university, studying music and fine arts. He has taken courses in tax preparation and needs a job to help pay for fees and books.

Manassas’ Hispanic population rose to 11,876 in 2010, or 31 percent of the population, more than doubling from 15.1 percent or 5,316 in 2000, according to city figures. The number of Hispanic students grew to 3,629 in the last academic year, about 51 percent of the total, from 27 percent in 2003-2004.

The city’s Southern identity – a Civil War battlefield is close by and streets bear names like Reb Yank Drive – competes with signs of Hispanic influence. Shopping centers host stores such as Video Mexico and Taqueria Tres Reyes, where goat-meat tacos can be purchased with a tall glass of “horchata,” a sweet beverage made with rice milk and almonds.

“One of the first things I asked is how do we speak to people who don’t speak English?” says Catherine Magouyrk, who was appointed superintendent of the city’s schools this year. She spent $15,000 on translation equipment so parents could understand what was going on at back-to-school nights.

The town in May also elected Ilka Chavez to the school board, its first Hispanic member.

“I am here for all the kids,” Chavez says. “But if we can move and engage the Hispanic population, it will stabilize the system across the board.”

The city had 186 Hispanic students in its Class of 2012 cohort, according to state data. Of those, 69 percent graduated on time according to state criteria, while 14.5 percent dropped out. That compares with an 89 percent graduation rate for 202 whites and a dropout rate of 3.5 percent.

Magouyrk, interviewed in her office just a few steps away from the high school, says she is meeting quarterly with all students to hear them out.

“There isn’t just one answer,” she says. “It will take a multifaceted approach to meet the variety of needs of all our students.”

Her aim is to keep information, counseling and goals in front of teens so they remain focused on a career or college path and don’t drop out. She says local churches, which get the word out to parents, are big allies in the effort.

NEEDED: ROLE MODELS, BETTER INFORMATION

The Rev. Ramon Dominguez, a Catholic priest who has worked with more than 200 children in his tutoring program at Georgetown South, says Hispanic teens need role models, better information and more hands-on guidance.

“We are talking about capable American citizens who are born here who are just stuck,” Dominguez says. “A number of them would like to go to college and don’t know if they would be able to afford it.”

“Immigration status is a big obstacle for capable students who can’t access the university system,” he adds.

Obama’s young-immigrant amnesty program doesn’t override the patchwork of in-state tuition policies. Currently, 14 states allow students who meet requirements to pay in-state tuition rates at public colleges regardless of their immigration status, according to Tanya Broder, senior attorney in Oakland, California for the National Immigration Law Center.

Meg Carroll, a former Manassas police officer who speaks Spanish and is now the manager for the Georgetown South community council, says Latinos understand the value of education.

The parents just can’t manage the language or the daily decisions that need to be made to navigate the schools. This year she started a tutoring program. After putting up just a few fliers, 50 parents showed up with their children the first night.

“They hate being not able to help their children” because of language barriers, says Carroll, who plans to double and maybe even triple the number of tutors involved. “They come here saying, ‘We want our children to succeed. We just can’t help them.’ “

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.