ROCKPORT — The Center for Furniture Craftsmanship smells like a bakery. Peter Korn, the center’s founder and executive director, is a weekend baker, although his pursuit of the leaven arts often blends into the work week.

Just as the smell of wood fills the workshops here, the aroma of baking bread fills the offices.

Korn, who turns 62 this month, has been a dedicated baker since college. He loves the simplicity of the craft: Mixing ingredients, working them and adding a personal touch. The result is a thing of beauty.

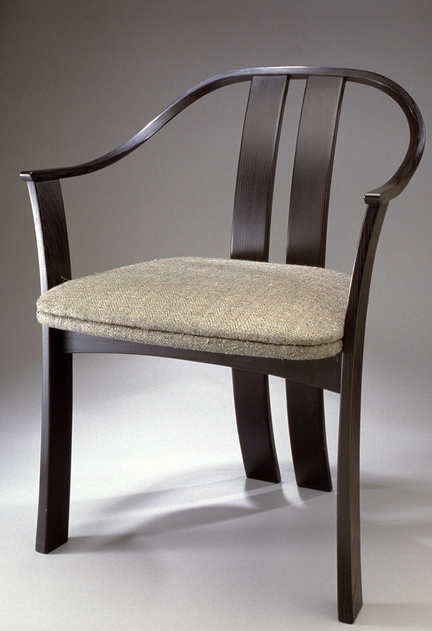

It’s a similar satisfaction that he enjoys when designing and making a beautiful desk or chair.

Korn explores the nature and reward of the creative process in a new book, “Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman.”

A master wood worker, Korn has written how-to books in the past. “Why We Make Things and Why It Matters” feels more like a memoir. Korn writes about his personal journey in pursuit of his craft and the satisfaction of being a successful creator, of making and shaping an object with one’s hands and mind.

He asks, how does the making of an object shape our identities? How does creative work inform society? What does the process of making say about us as individuals and as a society?

More personally, the book is a conversation about what it means to be human, what a good life is and how work fits into that. He writes about his two bouts with cancer, and how surviving Hodgkin’s disease informed and motivated his interests.

In many ways, Korn is an unlikely creator.

“I had no role models for doing anything with my hands growing up,” he said.

He was raised in a Philadelphia family that stressed intellectual pursuits. His father expected his son to become a doctor or lawyer. Korn studied history at the University of Pennsylvania.

The first time he worked with his hands was as a summer carpenter on Nantucket in the 1970s. He liked the physical work, and felt satisfied making things well.

Friends of his were having a baby, the first of his contemporaries to have a child. Korn bought materials three days before the baby was due, and spent the next 72 hours making a cradle from his will and intent.

The event changed his life.

It set him on a path as a self-sustaining furniture maker, leading him first to New York City, where he sold his work, to Anderson Ranch in Colorado, where he taught, and eventually to Rockport in 1993, where he opened the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship.

He directs the nonprofit school, which has a budget of about $1.2 million. Each year, the school teaches about 400 students how to design and make beautiful things with their hands from wood. Some are functional pieces of furniture, others are more sculptural in their approach.

At any given time, 30 to 50 students are on campus, filling the workshops with energy, sawdust and, ultimately, art.

Some pay $1,300 for a two-week basic wood working class. Others pay nearly $19,000 for a nine-month intensive that culminates with a group exhibition in the school’s Messler Gallery on campus.

While the outcome of the student experience at the school is a tangible object, Korn is really teaching what it means to live a satisfied life. Four decades of creativity have revealed to him that the satisfaction of being creative is not necessarily the finished piece, but the act of making.

“The world is not begging for another chair or another desk,” he said. “When we go into the studio to create these things, we feel that by going through the process we will emerge at the other end as a different person.”

Creative work is a source of fulfillment, Korn said, “but only while we’re doing the work.”

Korn still makes furniture, on average one piece a year. He chooses his projects carefully, often a gift for a friend. The last thing he built was a dining room table in 2012.

Surviving Hodgkin’s disease twice – the first time when he was 27 and again when he was 46 – taught him to cherish his time and fill it with worthy endeavor.

The first time he got sick, he was given slightly better than 50-50 odds at survival. He was young, and certainly didn’t want to lose his life. But he accepted death as a possibility. The second time, his odds were much worse: 15 percent.

By then, in middle age, he very much wanted to live. He had found his purpose and passion, and wanted the chance for continued fulfillment.

Today, Korn mostly teaches. And writes.

He’s an avid reader, and has always enjoyed writing. But until “Why We Make Things and Why It Matters,” he focused his writing on how-to books. This one is different.

He began writing it in 2005. Daunted by the task of a more personal story, he vowed to write incrementally. He had been thinking of these themes for years, so his concept was well entrenched. But the act of writing challenged him.

Including edits and rewrites, he averaged 30 words a day.

Writing well is hard work, he said, calling attention to a cartoon hanging in his office at the school. In the cartoon, a prisoner is tied to the rack. The executioner admonishes, “Don’t talk to me about suffering – in my spare time, I’m a writer.”

He hopes that people who read this book share an appreciation for the value of work well done, for a focused effort.

In this case, value is not monetary, he said.

“You can have all the money in the world, but there’s not a person who has all the money in the world who says their fulfillment comes from the money,” he said.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be reached at 791-6457 or:bkeyes@pressherald.comTwitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.