William Manning and Frederick Lynch are doyens of Maine painting. Both have been abstract painters of extraordinary ethic and energy for more than 50 years.

And while they comprise a notable pairing with shared forms, concerns and visual vocabulary, it is probably better their two shows occupy separate floors of Icon Contemporary. Each has such a powerful presence that it is hard to imagine Manning’s and Lynch’s new works hanging in the same room.

Manning works in acrylic on masonite (an appropriately old-school support that is becoming more and more common as panels have finally overtaken canvas).

In fact, Manning leaves at least a masonite margin on each work to play up the idea of painting as field and shape. He works largely in hard edge forms in a bold but organic palette. The shape/surface relation is often dynamic to the point of dizzying: Tilted rectangles and forms twist and contort the shape of the panel as it relates to the margin and frame to such an extent that Manning’s paintings almost never look straight once you engage with the image.

But this happens in real time, so it doesn’t interfere with their handsome posture as art objects; they just happen to resist expectations much like, say, a teenager resists parental authority.

This sense of resistance is why these are ultimately modernist paintings. Moving beyond push/pull formalism, the most satisfying modernist paintings have a pushback attitude.

The key is the conflict about whether the painting is actually independent of the viewer or not. How the viewer or artist resolves this question with any given work just may be the fundamental narrative of abstract painting over the last 100 years.

Abstraction, in other words, is about attitude and disposition.

Manning matches his attitude with intelligence. His colors and shapes question themselves as much as the viewer and invite the viewer to join in and experience the ride for her/himself. Corners, margins, shapes, design, composition, edges and how they relate to create a painting are all put in play.

All you have to do is follow your eyes and Manning’s works give you a lesson in the language of painting. Because of their dynamism, your perspective becomes the gathering point for your observations and experience. Instead of making you follow their internal logic like a rebus, Manning’s paintings present themselves for you to unravel so that the experience of visual intelligence lies with you.

Spending a few minutes with any of Manning’s paintings is extraordinarily satisfying. And there are no wrong turns.

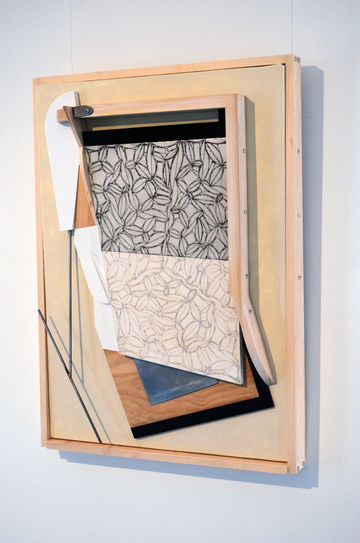

A particularly important quality of Manning’s paintings for this show is his use of collage: He paints on watercolor paper and uses these as swatches in his compositions.

These bits often act like brushy paintings or complete phrases; but sometimes, they simply serve to motivate Manning’s gestured steps and wind up invisible under so many other smartly placed layers of paint.

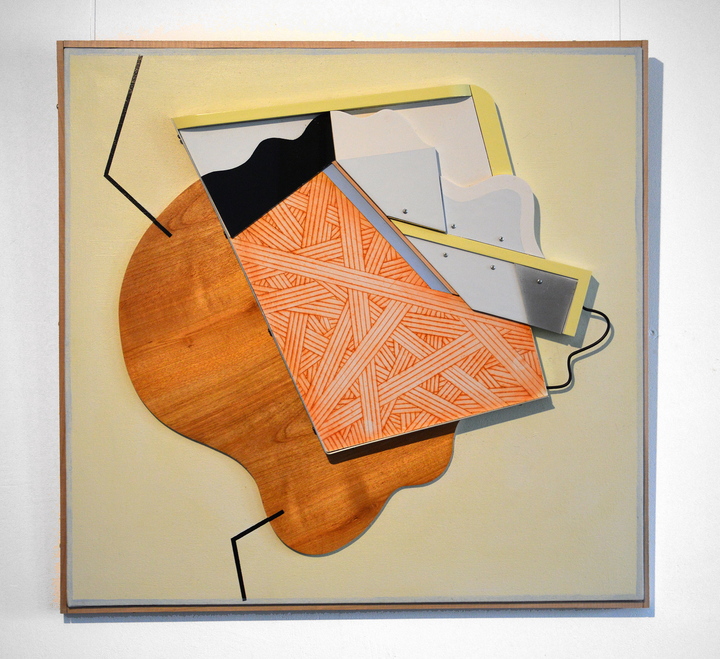

LYNCH’S RELIEF sculptures are in fact directly geared to the fundamentally important moment of modernism known as Synthetic Cubism, during which Braque invented collage while he and his partner, Picasso, expansively explored the possibilities of painting.

A bit of newspaper came to stand for a newspaper, a scrap of wallpaper became the caning of a chair, a faux finish comb made wood or hair and so on.

Lynch visits the language of Cubism as the language of possibility in painting. But he takes it in the direction of painting as object by playing with frames, supports, painting surfaces, color, different types of paint and then the languages of shapes and styles.

From an art history standpoint, it’s like a body of work intended to illustrate the relationship between abstract Constructivism and Cubism. (This matters because Tatlin’s abstract Constructivism came from his direct experience of masterpieces of Picasso’s Cubism on view in Russia – and Cubism never actually became totally abstract.)

But while Lynch bows in respect to the artists whose language he borrows (Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Tatlin, Malevich, Jasper Johns, etc.), he never drops their names or relies on the viewer getting the reference in order to understand the work.

And this is precisely what makes Lynch’s work modernist rather than post-modern: The success of the work is based on internal structures and content that are put into play by the viewer’s experience rather than by required external knowledge.

Post-modernism has infused so much irony and snide parody into the language of art that we often hesitate to trust our sensibilities and instincts.

But both Lynch’s and Manning’s works are made to be seen in good faith. No ironic references have to be parsed in order to understand it.

And it is fundamentally geared to the viewer’s here-and-now experience. (Lynch’s witty references to gallerist Duane Paluska’s constructions are warmly – even lovingly – inclusive of his dealer, not parodic or ironical.)

The key word here is “faith.” Manning and Lynch cut their artistic teeth at a time when no one doubted painting was important. Audiences assumed integrity from artists who, in turn, assumed integrity on the part of the audience.

Manning and Lynch are extraordinary and accomplished artists whose work hasn’t faded one iota over the years.

Their works stand as tall reminders that our personal experience of intelligent or spiritually compelling art doesn’t have to be lorded over by bombastic pretense or self-aggrandizing theatricality.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.