Bates College Museum of Art in Lewiston is offering three shows; two of which I would call traditional. The third is so nontraditional that it challenges my expectations.

To add weight to its novelty, a portion of that third — “Color at the Center” by Fransje Killaars — is not presented in the museum itself, but is instead sited on the second floor of Mill #1, a great chamber in the historic Bates Mill Complex in another part of Lewiston.

Killaars works in Amsterdam, and is widely recognized in Europe as a premier installation artist. Her textiles have a soft visual elegance, but serve primarily as vehicles for the colors that infuse them.

Those colors are often raised to the broiling point. Some are superintended by simple geometric grids; others inhabit the grids themselves and, when fluorescent, are barely under control. The juxtaposition between intensities may be so violent that a piece can drift toward surrealism (except perhaps in India). These textiles are not resting places for the eye.

While Killaars is an installation artist, a textile hung on a wall and presented as a painting has an apologetic quality. It is not a painting; it was made for another purpose and looks awkward.

Killaars, on the other hand, presents her textiles as components in large forms. As such, they interact with one another within the form. They do not appear for their own values; they are not individual performers and they offer no narrative meaning. They don’t in themselves tell stories.

There are three principal installations in that great mill room. Relieved of the once endless lines of looms, the flow of space in the now vacant chamber is interrupted solely by a march of thin columns. Space is allowed to enter as an element.

Tucked amongt that embrace of space are the site-specific “24 Hours No. 2” and “Maine Mill Figures,” as well as “Figure,” a sculpture that has appeared in other venues

“24 Hours No. 2” is an abstraction of a textile-covered bed attended by a lone draped figure. “Maine Mill Figures” combines a number of draped figures attending horizontal forms that have been covered by old Bates bedspreads. The chamber in which this takes place is the room in which the bedspreads were woven.

The interaction between the extravagance of Killaars’ draped figures and the birthplace of the very sedate spreads is almost shattering. The figures seem elegiacally involved in the material culture of the community. They mourn for the days of its textiles.

Killaars does not assign a narrative meaning to her work. It is non-specific. Each piece and the place in which it stands will have the meaning that the viewer brings to it. I wouldn’t expect viewers from textile communities to bring with them the same thoughts as those from communities that had no mills.

In entering that magnificent building, climbing the heavy staircase to the second floor and then being confronted by the vastness of the chamber and Killaars’ installations in spatially distant locations within it, you sense that space and the objects Killaars has provided have combined to create the work. It takes a place such as Mill #1 to make the point a reality.

My instincts tell me you will never have an opportunity like this again. This portion of the event was jointly achieved by the Bates Museum and Museum L-A, a remarkably vital Lewiston-Auburn museum that charts the work and life in Maine’s second-largest community.

Its premises adjoin that of the show, and its combining with Bates in an event of this size is a significant community effort. I dare not say that a partnership such as this is unique in Maine, but considering its scale, it might be.

The other half of the Killaars exhibition is at the Bates Museum itself. It continues the artist’s effort to place color at the center of art in the form of rich cultural statements.

In “Figures,” an installation that pretty much absorbs the upper gallery, the color-draped forms and textile lengths that were presented in Mill #1 reappear, but contrasted with 33 white or lightly toned antique garments.

The color-draped forms flow in an easy sequence from the entrance of the gallery. When the line ends, the viewer is required to turn, and in doing so faces a long vertical arrangement of the essentially colorless women’s and children’s garments.

Those articles, drained of their life force, seem to be surrogates for their former wearers who, like them, are drained of their life force. In this environment, color is at the center of life.

This ambitious exhibition is Killaars’ first large solo exhibition in the United States, and Maine is fortunate to have it.

ALSO OPENING US to the great “out there” are two additional shows at Bates.

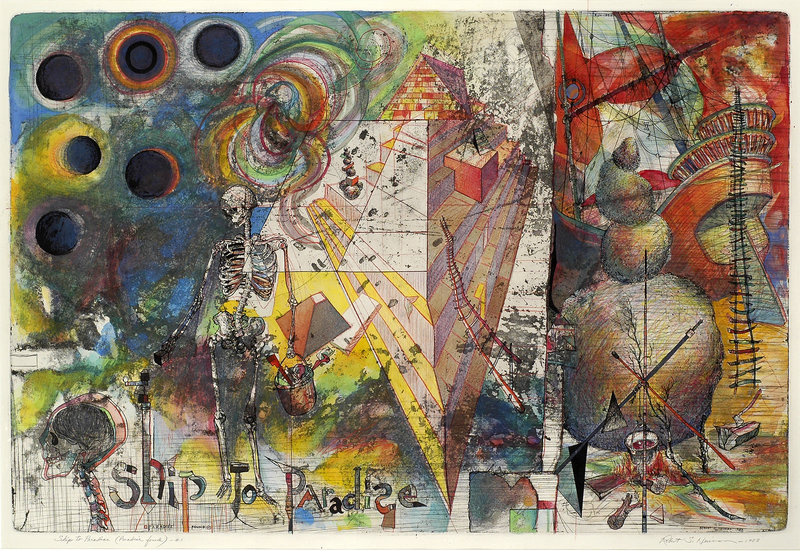

One is Robert S. Neuman’s “Ship to Paradise”; the other is Max Klinger’s “The Intermezzi Portfolio.” Both artists were previously unknown to me, and are fascinating.

Neuman’s work is a contemporary commentary on the human condition prompted by Sebastian Brandt’s “Shyp of Fooles,” a 15th-century satire illustrated by Albrecht Durer. In various print media, Neuman takes us through the construction, voyage and ignominious end of a vessel unsuited for its ambition.

His draftsmanship is elegant, infinitely complex and crowded with references drawn from more sources than I can, or be expected to, know, and are richly gratifying. Neuman’s fantasies are sophisticated kindly ambulations through time and cultures.

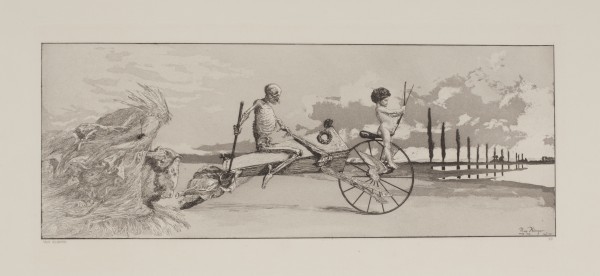

Max Klinger’s (1857-1920) “Intermezzi” is a wistful assembly of etchings and aquatints embracing such themes as desire, fantasy and, of course, death. They are extremely beautiful and insistent.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.