A building is an extension of its owner’s persona. I extend that maxim to include the manner in which the owner outfits the building. You can tell a lot about a person by looking at where he or she lives.

That is never more so than in the case of an artist. I read an artist’s home as an accompaniment to his art and a declaration of his values. It doesn’t always work, but I keep looking.

That brings me to Winslow Homer, Prout’s Neck and the Portland Museum of Art. Homer’s studio/home at Prout’s Neck goes back to the early 1880s, and by the time I first got there — the misty 1960s — it was an object of mild curiosity, not the venerated site it has since become. I was looking for the personality of Homer — it might have soaked into the boards — but all I found was the standard account of his life and visual confusion. I was denied a brush with the occult. Homer had fled.

The museum’s recent acquisition and restoration of the studio was heroic. Both concealed and unconcealed, the modifications refresh the old place and suggest spaces in which Homer’s genius could wax.

The efforts have preserved the essence of the studio, made the building comprehensible and reduced some of the mystery that we, through lack of information, have contributed to Homer’s life.

Among the commemorations of its efforts, the museum has sponsored “Between Past and Present: The Homer Studio Photographic Project.” It is an exhibition of photographs relating to the studio and neighboring lands by five distinguished photographers.

They were selected for the accomplishment of their imagery — each is capable of brilliant work — and for the ability to work in one of the historic processes available during Homer’s lifetime (1836-1910). The goals of the project were to record and interpret. The results make up the show, and provide me with considerable pleasure.

“Pleasure” is not a common term of art commentary, but it is particularly apt for this event. The restoration of a notable structure is always a rich cause for comment and concern. This in itself gives the undertakings at the studio a certain fascination.

Further, I am enthusiastic about the preservation and use of arcane photographic processes even when diluted by well-meaning digitalists. The appearance here of several old methods also is fascinating. Add all of this to a number of strong images, and you have a very good show.

The museum’s selectees are Keliy Anderson-Staley, Tillman Crane, Brenton Hamilton, Abelardo Morell and Alan Vlach.

Anderson-Staley is a noted maker of wet-plate collodion tintypes. This, among other things, means that her darkroom travels with her when she works in the field. That effort gives her plein air images a certain enchantment; they tug at the early history of recording visual facts.

Anderson-Staley’s “Winslow Homer’s Studio, Viewed from the Sea Path,” which started life as an 8-by-10-inch wet-plate collodion tintype, is splendid. In it, the old studio is embraced by a landscape that has much in common with the world that drew the Homer family to Prout’s Neck. Of all the work on view, Homer makes his most sustained appearance in Anderson-Staley’s.

Crane’s 10 images range from the architecturally examined “Roof Corner Homer Studio, Scarborough, ME” to staircases, bird’s-eye views of the roof, piazza railings and interiors, and passages of nearby lands. Accomplished in platinum, they are the most comprehensive study of the physical sense of the studio in the show.

Hamilton has brought his eye for capturing visitations from esoteric forms to facts relating to Prout’s Neck. Interpreted in equally esoteric gum bichromate, things and places evoked by thoughts of Homer and his work require the cooperation of the viewer.

Morell is one of the most admired contemporary photographers in the country. I have watched his progress since his student days at Bowdoin College, and am fascinated by the freshness of his subject matter and his remarkable ways of extracting it. His successive bodies of work have been, in their several ways, memorable.

I cannot be as fulsome for “Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of the Sea from Winslow Homer’s Backyard, Prout’s Neck, Maine.” Hamilton’s single entrant, it is an apparently difficult camera obscura achievement, but is either too general or too subtle to enhance my sense of the milieu of the studio.

Vlach works in salted paper, an antique medium involving the production of photo-sensitive silver chromide and a great deal more. It brings a deeply stained roughness to the images, and I find that irresistible. This is photography in one of its earliest and most indelible forms.

Vlach’s print “The Painting Studio” is formidable, as are his several views of Cliff Walk. As to the latter, I wonder whether Vlach had the landscape itself in mind or Homer’s own images of it. Either way, it’s a complement to a fine body of work.

“PRESSING ON II” at June Fitzpatrick Gallery in Portland, curated by Bruce Brown, is a 20-artist event.

Lively and varied, it offers less by way of adventure than it does by way of fine quality. Familiar names — not necessarily in familiar mediums — give it particular interest. There are many names in it that are new to me and worthy of brisk applause.

As its title implies, this is an exhibition of printmaking. As such, it is no surprise to find works by Charlie Hewitt or Tom Hall or a couple of monoprints by John Wissemann.

On the other hand, I did not anticipate prints from Kenny Cole or a lithograph by Alan Bray; I think of both artists as painters.

As to Hewitt, the persuasiveness of “Green Light” represents this formidable artist at a recent and fine point in his career.

Wissemann’s works, in black and white and in geometric formation, provide animated notations about the business of harbors. Piers, trucks, lifts and the like appear, move on and reappear at selected moments.

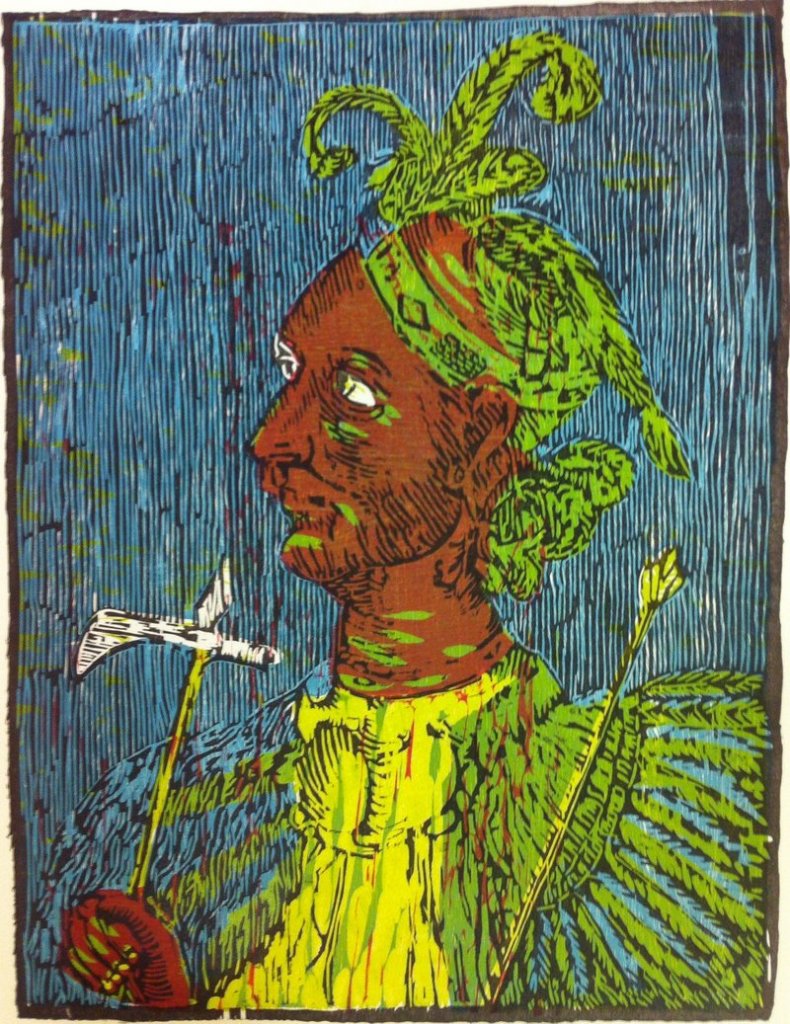

I note two powerful lithographs by David Wolfe: “Chiucco, The Long Warrior” and “Wanahton, a Yankton Chief.” They have a depth and pathos equal to their subject matter, and suggest themselves as units in a series to come.

Cole’s silkscreens follow the paths of the surreal. In “Triumvirate Sky,” three cameras on tripods point at a thinly crescented moon. One records the discovery of an atomic explosion, another depicts a drone warplane, and the third records the finding of a crucifixion group. In his “Evening Sky,” heavy truck tires bounce around a sky channeled with colors that match its title.

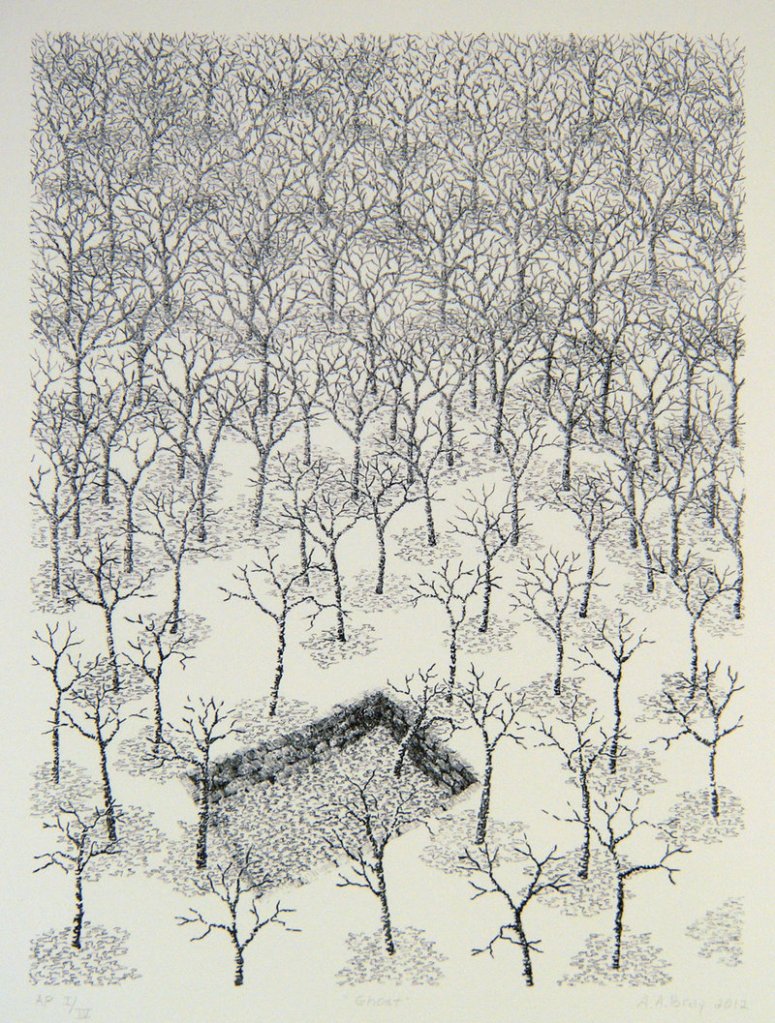

I also note Bray’s lithograph “Ghost.” It tells of an ephemeral forest with one tree that punctures the foundation of a long-gone building. Tim Higbee’s “Islesboro” is a luxurious soak in color.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.