PORTLAND — Will Barnet spent many of his summers painting in Maine. Considering the artist turns 100 this month, we’re talking about a lot of summers and very deep roots.

To celebrate Barnet’s milestone, the Portland Museum of Art has mounted a disappointingly limited but nonetheless delightful little show, “Will Barnet at 100.”

Barnet is easy to recognize and even easier to misunderstand. His work is so graceful and so locked into seemingly simple design-oriented compositions that your eye is comfortable with them almost immediately.

If you only pass by his work, you might think Barnet is a decorative lightweight.

But you would be wrong. Very wrong, actually.

Barnet has always been obsessive and deeply sophisticated. To capture apparently simple scenes, he has often kept his work in his studio for years until confident of achieving the highest level of perfection possible without even the faintest wisp of fussiness.

Barnet’s painting “Winter Sky” (1985) reveals why it’s so easy to underestimate him. In the horizontal snowy seascape, the ocean lies absolutely still and flat on the horizon. Two cloaked female figures stand looking out to sea. Eleven black crows populate the white-snow ground.

The women are highly stylized: monochrome outfits and black hair tied in tight round buns. The crepuscular sky shimmers down evenly from gray-blue to teal to pink. The paint is so thin, it reveals the texture of the canvas.

Yet, from very close up, we see the lines are surprisingly soft and un-sharp considering the insistent geometrical logic of all the forms. To our surprise, we see (as in many of his paintings) that Barnet’s underlying pencil marks deliver much of the descriptive detail in the work.

What looked so smooth and perfected from a distance is almost painfully simplified from a couple of feet away. The lack of slick lines reveals that the intellectual Barnet is deeply engaged with slowing down the viewer’s eyes. He wants to showcase the forms not as individual shapes but as supremely balanced geometrical components of his virtuoso compositions.

The left figure is seen in profile, and her blue shirt’s lines are softly smeared. Barnet could simply have painted a pair of white lines in two strokes over the flat blue, but instead took a great deal of time to build up these soft little forms. Hidden within her almost monochromatic gray-plum tunic is a set of curving drapery lines that would have made Cimabue green with envy.

While “Will Barnet at 100” is disappointingly thin (three paintings, one drawing, one abstraction and six other prints), it encourages you to linger — which makes all the difference with Barnet.

And linger I did with the surprisingly mysterious “Mantle,” which I love. An old woman stands facing the viewer, but with her head turned in profile. The space is sculpted by rectangular forms: a bookcase, the mantle, a pair of door frames through which you see a window and a boxy clock on a cabinet.

The clock form is echoed by 10 rectangles on the mantle — maybe cards from a holiday. Her hands reach up toward her face, surprised by the time. The far clock’s hands show 4 p.m., and the object on the left side of the mantle echoes the form of the square clock with the round face. A rectangular painting of a chicken hangs above the mantle, humorously veiling her fear of old age.

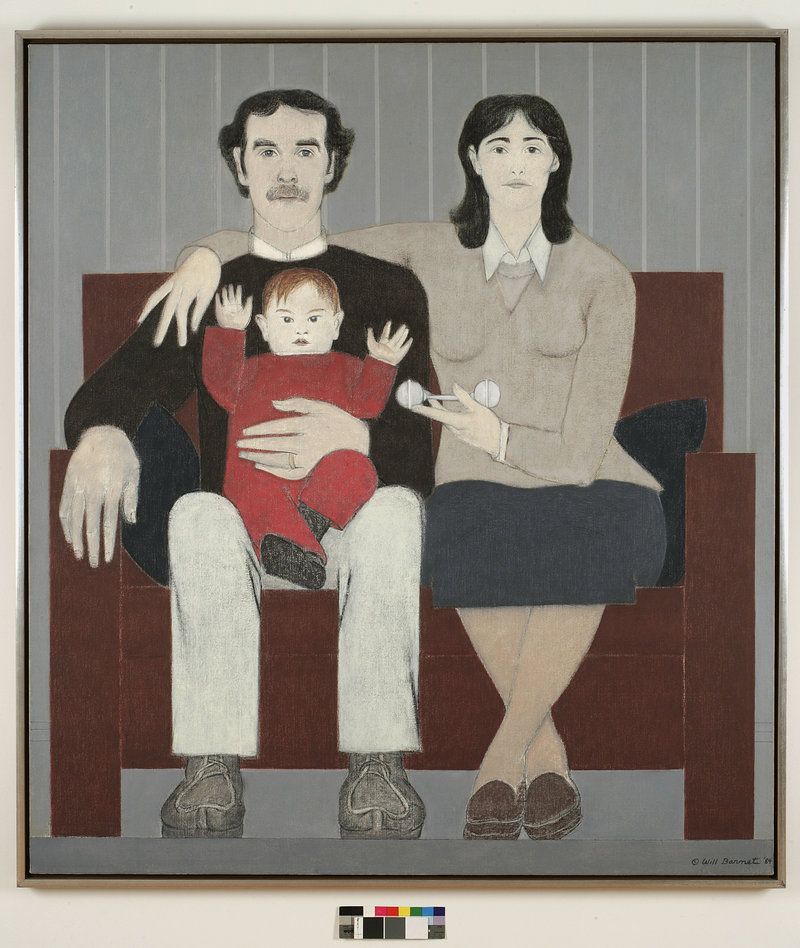

While each of the three paintings is worth a long look, we most often associate Barnet with his graphics, as they so perfectly match his attractively elegant and stylized images of his pretty wife. Most often, we see her as a brooding sea wife — waiting dutifully in the well-experienced poses of over-practiced and feigned patience.

With the loving eye of the long-overdue Odysseus, Barnet dreamily stands by his patient Penelope. (The classical themes apparent in the titles of Barnet’s graphic works — “Persephone” and “Ariadne,” for example — accidentally vaunt his quiet obsession with timelessness.)

Although echoing the slender curves of Art Deco with the body of a real woman, Barnet’s distilled forms reach for the ages rather than the quickened legibility of passing seconds. His gestures toward idealized forms are his attempts to stay time. His obsessive picturing, he seems to believe, will hold his loved ones here forever. Barnet’s faith — effective or not — is to our shared, if quiet, delight.

Barnet’s earliest works in the show prove he could draw brilliantly (“The Nurse”) and that his abstractions (the dancy and deliriously delicious eight-color print “Wine, Women & Song”) might have been his best work, but patience with his later (if un-hip) works proves most worthy.

“Will Barnet at 100” is hardly the full celebration the artist deserves. But this sliver of cake delivers beyond its cold, white icing.

One of America’s greatest artists, Barnet’s genius lies in his reserve rather than his bravado.

Maybe Barnet should get more from Maine on his 100th birthday, but this party is for all of us, and it’s not to be missed.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.