When the product in question is a highly finished object, the pairing of patience with technique often makes for a curious territory between process-oriented art and fine craft.

This is one reason I don’t think there is ultimately a meaningful distinction between art and craft. As far as I am concerned, they are components of each other, and the real distinction we usually want to make is separating art from kitsch.

Many artists anxiously define themselves with fancy names like “conceptualist” or “process artist,” and that’s fine. But I am far more impressed by the artists who have set out to explore the no-man’s land of craft/process art or maybe even claim it for themselves.

Two such artists are showing together in “Graphite” at Icon in Brunswick: Kate Beck and James Marshall.

Readers who know their work might bristle at the “craft” connection, but showing their art together makes a case: Both work obsessively with graphite and paper through strict and laborious processes, and both make exquisite objects that revel in the physical qualities of graphite and paper.

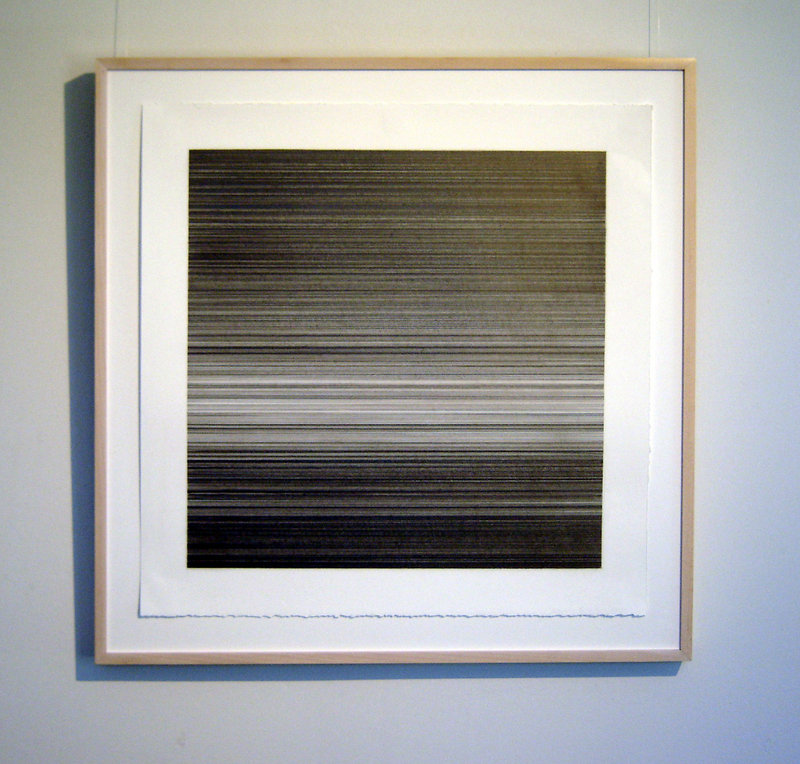

Beck’s new drawings feature horizontal lines in rectangular formats. They are about time, space, intimacy, form and a here-and-now spiritual quality.

Marshall’s drawings feature modular groups of circles of swirling pencil lines made with such rigor, intensity and repetitiveness that the graphite shines brilliantly and the paper support swells as though sore from the obsessive workout. This plays up the drawings’ material, status as objects and even sculptural values, and it forces the idea that repetition has genuine physical effects.

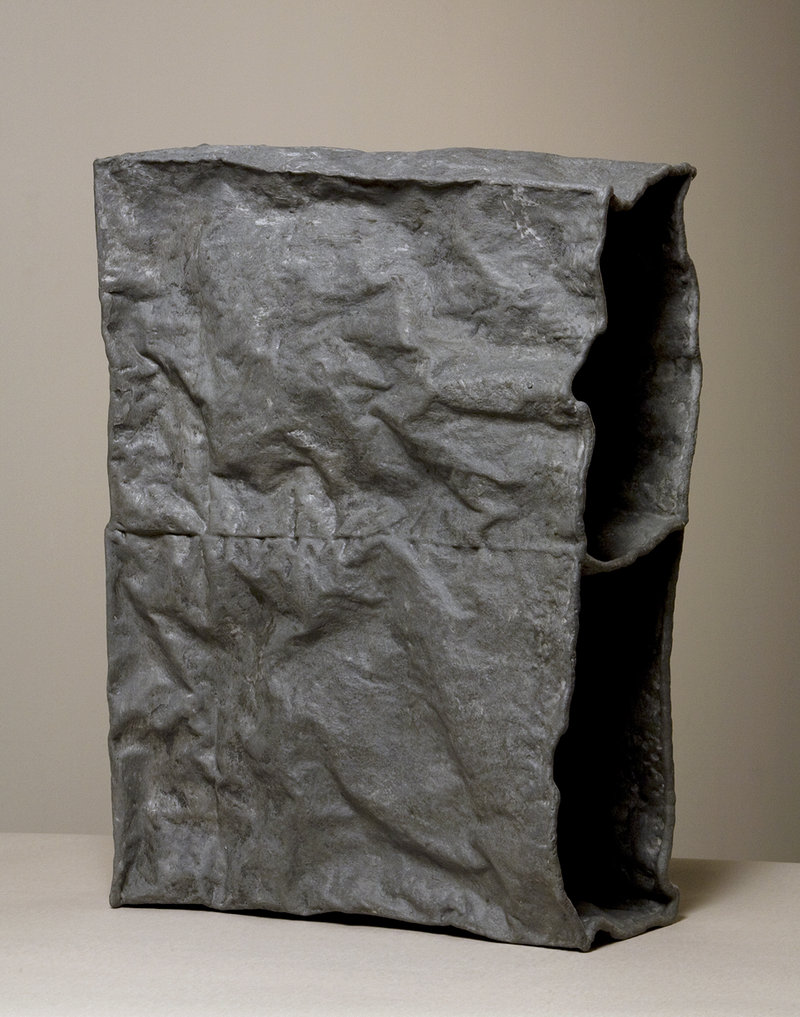

More important to this exhibition, however, are Marshall’s sculptures: Paper bags that have been covered in dozens of layers of his own mixture of PVA (polyvinyl acetate, the main ingredient in white glue), graphite and plaster.

Some of these are shown folded and flat on the wall, but most are open to full volume (having been rebuilt, since Marshall’s medium makes them collapse). Their built-up layers of glue create a lumpy surface — as though heavily painted — but with enough of the folds and crumple creases to remind us of the structural integrity of the paper bag itself.

The bags’ function, volume and recognizable utilitarianism bring these sculptures fully into the vessel tradition (read: craft), while the built-up surface fully removes them from still appearing functional.

Their artistic irony is that they are graphite and paper — essential drawings. There is something of Warhol’s “Brillo Box” logic here (rendering the commonplace as art), and I can see how the Duchamps’ “readymade” concept could be argued convincingly. But the number of bag pieces and their modular deployment pull them back to a position closer to process, component and craft rather than conceptual gestures, in which the obvious fine-art process announces their clear intentions.

If you like shades of gray, then Icon has rarely (if ever) looked better. Both artists’ drawings are elegantly framed, and the show is nicely laid out. Even the gallery’s industrial gray carpet adds to the installation.

While Beck’s drawings are attractive, don’t expect Marshall’s bag pieces to be aesthetically appealing, despite the fact they drive the look of the show. You could call them sexy, maybe, because they are ironically cool and smart, but Marshall’s bags are hardly pretty.

Next to Marshall’s work, the luminous qualities of Beck’s denser passages of graphite pop more than they would alone. This has the effect of making them easier to read as objects, but it also hides some of their best qualities.

Beck’s “Essential Abstraction” is a relatively small vertical rectangular form on a large square piece of deckle edge paper. The form is dense with solid lines surrounding its horizontal rhythms, but the context of the show might lead your eye away from noticing the tiny lines at the corners, critically hinting at their key geometries.

“Earth-Sky {Posture}” is another of Beck’s hidden geometry pieces. A horizontal rectangle is blank on top and dense with pulsing striations on the bottom. Less obvious is the third term – the space above the lines where a third band would perfectly fit.

While I appreciate the (abstruse?) geometrical gestures, I prefer Beck’s squares and their experiential insistence – which is also why I think I prefer the effect of Marshall’s rather obvious drawings to that of his bags and their multitudinous subtleties and secrets.

To get the bags, you need background on them that isn’t available just by looking. If Marshall could take the insights and breakthroughs of his bags and make them as approachably legible as his drawings, they could be great. But for now, he seems to be – lamentably – moving away from us, his audience.

Still, I would rather see 100 shows go over the deep end of concept and craft than even one more that sleeps so tiredly on the same old bed of the tried and true. Marshall’s motions are brilliant, even if frustratingly flawed.

“Graphite” is a great show with much to see and much to think about. In the year of the statewide Maine Drawing Project, it has been my favorite drawing show so far.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.