“Someone — I wish I could remember who — has since described me as ‘a man in the woods with his head full of books, and a man in books with his head full of the woods.’ “

So writes Sidney Lea, Vermont’s current poet laureate. Without sentiment but with a lot of love, his poetry celebrates his country neighbors and their hardscrabble lives.

Lea often heightens the psychological tension in a poem’s central drama with disparate elements pertaining to himself. Inevitably, one looks to Robert Frost (Vermont’s first poet laureate, incidentally) for comparison.

A couple of lines — buried in a stream of consciousness emanating from a dead skunk — struck me as both reminiscent of Frost’s most famous poem, “The Road Not Taken,” and altogether different. Instead of two roads diverging in a yellow wood and “leaves no step had trodden black”:

Five mountaintops bled

into mists to my east in New Hampshire. The sudden squalls spilled leaves on the woods-floor’s pall of nondescript hue.

Now he was dead. Now my brother was dead.

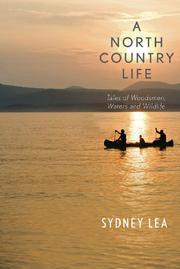

Lea’s literary output also includes a novel and several nonfiction books about hunting and his rambles in nature. His new book, “A North Country Life,” is a compilation of articles written for an array of magazines, mostly dating from the first decade of the present century. He has organized them here to follow the seasons of the year.

Month by month, a daybook entry describes some natural encounter on either a hike or a paddle and anchors, at least to some extent, the author in the present.

But this is above all a memoir, and it is never long before a memory takes over. In more extensive essays interspersed among these monthly markers, Lea eulogizes some of the “old-timers” he has known who have clearly had a profound effect upon his life. He also recalls his experiences as a hunter, cook, grandfather and friend.

Lea’s passion for hunting takes the stories all over the United States, but his two main stomping grounds are rural Vermont and, especially, the woods and waters around Maine’s Grand Lake Stream, which he has haunted for almost his entire life.

Toward the end, he describes his commitment to the local Maine Guides there — sons and daughters of his old mentors — and their efforts to protect the lands that remain the source of their livelihoods.

Coincidentally, I was involved early on in that excellent effort, but I never heard a more heartfelt raison d’etre for it than his: Preserving the memories of the woodsmen and guides, “people who have meant so much to me for as long as I have lived.” When Lea buys one of their cabins, a grouse hunting buddy — a local guide himself — supplies an apt coda: “Too bad you couldn’t buy the stories along with the camp.”

The next-best thing is to put at least some of them down on paper. In one chapter, having tape-recorded the stories of an ancient friend now deceased, Lea simply tosses aside his own word processor and transcribes the session verbatim. As he writes later on, “I couldn’t hope to celebrate the speech of upper New England by writing dialect, so damnably hard to construct without either condescension or embarrassing affectation.”

Bearing out his own verdict, this is the most “present” of the chapters in the book. “For better or worse,” Lea continues, “I thought if I chose a poetic vehicle, I might capture the rhythms and cadences of local speech without having to imitate it.”

In his poetry, Lea finds an authentically granitic ring. In his prose, having successfully warded off condescension and affectation, he does not always find a viable alternative. His default determination to present himself as an old codger “in the home stretch” of his life becomes at times lugubrious.

After reading several of his homages to individual woodsmen and women, it came to me that, in mourning their passing, these pieces are about Sydney Lea more than anyone else. “Elegy feels like posture, pretense, artifice,” he writes, and I couldn’t help agreeing with him.

At other times, though, Lea comes off the page with total innocent charm. After a delightful recollection of the old-time use of vanilla extract (80 percent proof) in a legally dry town — the local Independence Day dance “smelled for all the world like a pastry shop” — he admits, “I felt closer to my mentors whenever I slid some Baker’s (vanilla) into my own hip pocket.”

And anticipating a wild duck dinner on New Year’s Eve, he imagines the burst of memories in his head that will accompany the duck’s juices bursting on his palate. “It is perhaps the recollection of wood smoke that slightly burns my eyes until they water a little.”

Even if Lea’s poems reflect his perceptions to better advantage, there is still much to enjoy in “A North Country Life.”

Thomas Urquhart is a former director of Maine Audubon and author of “For the Beauty of the Earth.“

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.