Photographs can be remarkable for their inherent qualities as works of art. Or they can be remarkable because of what they depict. That the best photographers would routinely combine both sets of qualities is obvious.

But what is less obvious is how these affect each other. After all, sometimes the document and the work of art support each other, but very often, subjects will interrupt or even disrupt the more subtle qualities that a photographer has sought to capture in a given print.

Our culture demands photographs of important things, events and people. This puts photographers in direct contact with the most noteworthy happenings and humans. They are the surrogate witnesses of our culture. It is through them that we see modern history.

However, I am turned off by the idea of celebrity as a quality in itself, so I was not particularly interested in seeing “Making Faces: Photographic Portraits of Actors and Artists,” now on view at the Portland Museum of Art.

But I was very glad I did. Not only does it include some great and entertaining photography, it is split into two parts that together allow for a thoughtful consideration of the role of celebrity portraiture in an art museum.

The main part of the show features many great — and sometimes famous — pictures by important photographers. To say the least, it is entertaining.

But it also reminded me why I don’t like celebrity portraits in general. There is a picture of Tony Randall by Philippe Halsman, for example, that shows Randall yelling at a lion penned in a zoo. I always loved Randall’s hilariously neurotic character in “The Odd Couple,” but what a disappointing jerk he seems to be in this picture.

I could say similar things about photos of Lucille Ball, Ray Bolger and Ansel Adams. It’s not that they are misbehaving in the images, but the photos have little to do with their talents or accomplishments. A rare exception is Halsman’s 1950 photo of Milton Berle. It comes together as an artistic portrait that literally flickers with Berle’s playful wit.

Where “Making Faces” really begins to succeed is with portraits of artists in their studios. While many simply ride the celebrity of the artists (it’s hard not to “ooh” and “ahh” at Picasso or Fernand Leger, especially when photographed by the great Robert Doisneau), some offer amazing insights.

Seeing the stocky and cocky Le Corbusier in 1944 in his double-breasted leather coat standing over his paints and brushes, I felt myself torn between his messy boots-on-the-ground relation to his gear and what I have always held to be disturbingly fascistic tendencies in his “purist”-style paintings. Frankly, he looks like a Nazi in Doisneau’s photograph, and his troubling relationship to Nazism is a critical element of the conversation about his role in history.

Still, there is much to appreciate and enjoy in this show. Peter Ralston’s portrait of Andrew Wyeth and “Battleground” will lead to many amazed double-takes. Barbara Goodbody’s 1988 portrait of Robert Indiana on Vinalhaven is wonderfully jovial and lively.

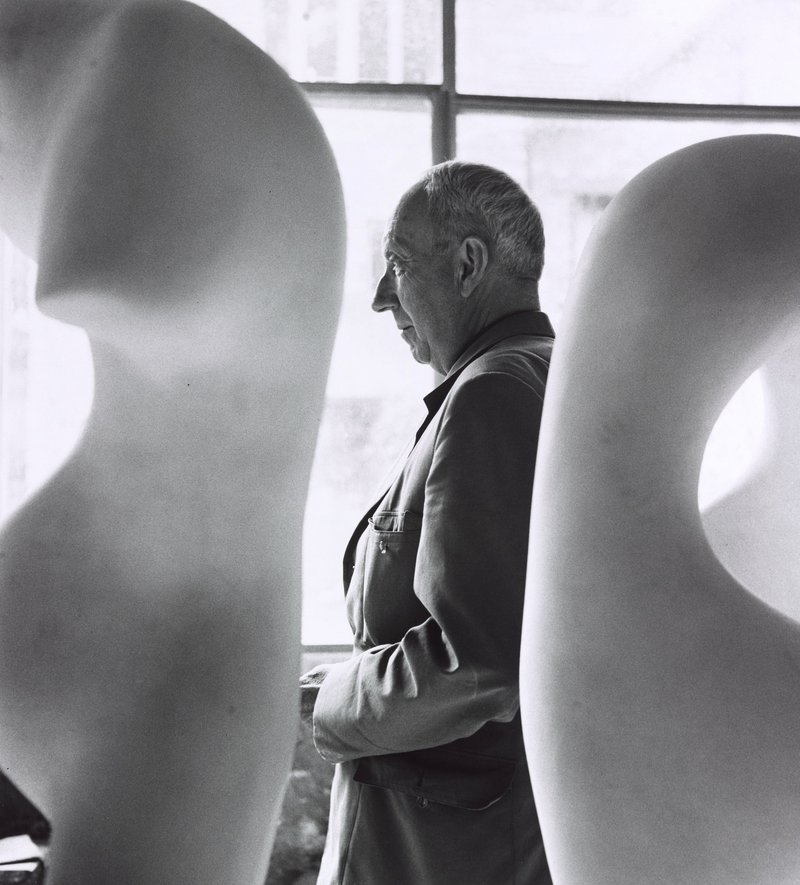

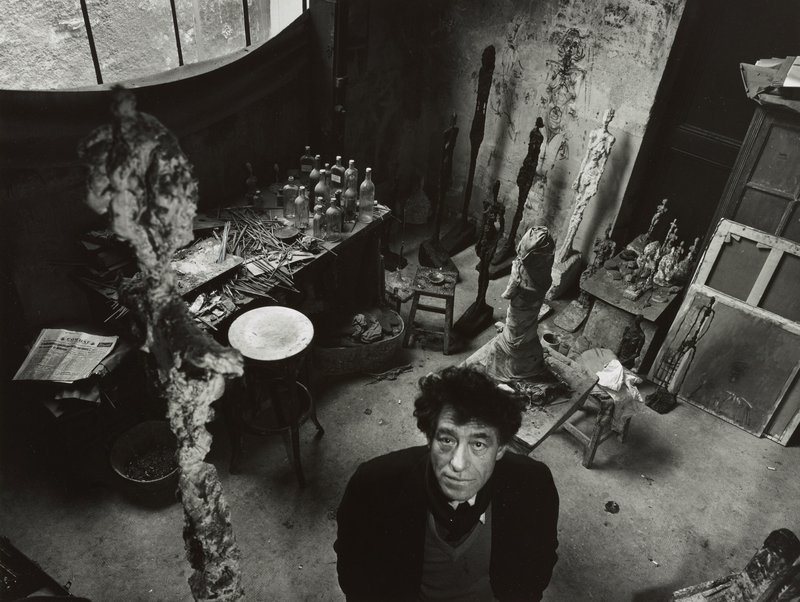

Doisneau’s portrait of Savignac playing chess with one of his paintings is brilliantly hilarious; his 1958 image of the sculptor Jean Arp through two of his marbles is serenely sophisticated (it’s much better than the Arp sculpture in the room); and his 1951 portrait looking down into the face of the great sculptor Alberto Giacometti in his studio is one of my favorite studio portraits of any artist. I could go on.

Yet is the second part of “Making Faces” that really lifts the show to another level. In a small gallery, works by a dozen artists have been paired with photographic portraits of them by David Etnier. It’s not as though Etnier is on the same level as Berenice Abbott or Doisneau, but at his best, he is very strong.

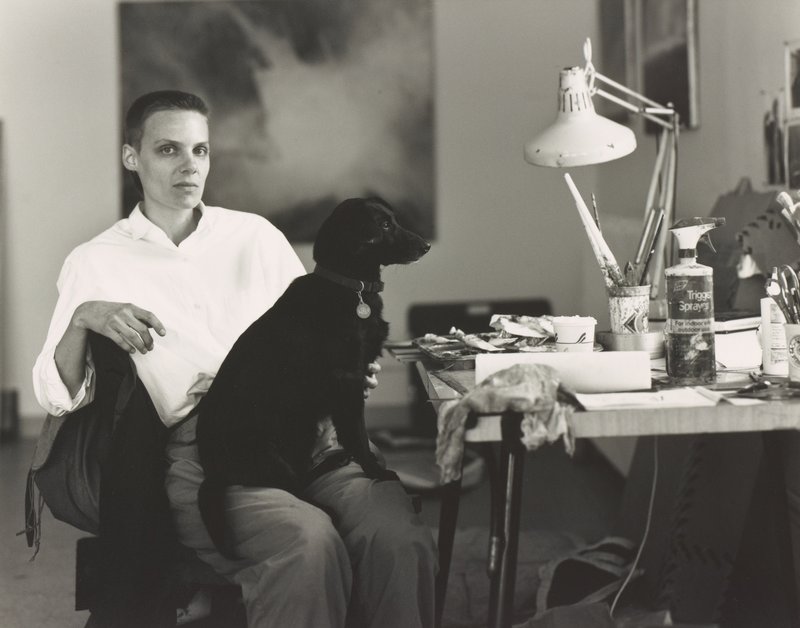

His portrait of Brett Bigbee, for example, is a great photograph: The stiff though delicately beautiful artist sits on a couch, uncannily balanced by a wispy but confrontational drawing of a recumbent nude. As well, Etnier’s image of Dozier Bell is stark and bristles with an alert intelligence so fitting to the artist and her work.

Many of the portraits show the artists at work, and that is somehow fitting for the Maine artistic ethic. It makes sense to see artists such as Linden Frederick, Chippy Chase (1908-1998) and Tom Crotty absorbed in their work.

The depicted artists’ work in the show is virtually all fantastic. My favorite is a tightly balled-up watercolor landscape (showing a train on a mountainside?) by John Heliker (1909-2000). It’s both powerfully dense and explosively exuberant.

I also particularly like Frederick’s ultra-realistic, dusk-lighted motel in Machias, Crotty’s surprisingly complex watercolor of a mitten-adorned boy holding tight to a yellow balloon, Eric Hopkins’ swooping 1988 island scene, and Richard Estes’ lapping-water scene painted with the gorgeously loose brush he seems to reserve for his more intimately scaled works.

Shown with works by their subjects, Etnier’s photographs feel like so much more than celebrity portraits. For the viewer, it makes for an unusually enlightening and interesting show — especially if you have any interest in Maine art.

It’s rare that I think a show is much better for being split into two distinct parts, but “Making Faces” is that exception. It is smart and thought-provoking.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.