Noriko Sakanishi’s “Confluence” at June Fitzpatrick Gallery in Portland features two bodies of work: Her system-oriented wall constructions and her exquisitely intimate collages.

And while Sakanishi’s painting-logic sculptures are her most ambitious work, her collages are more complex, striking and humanistic.

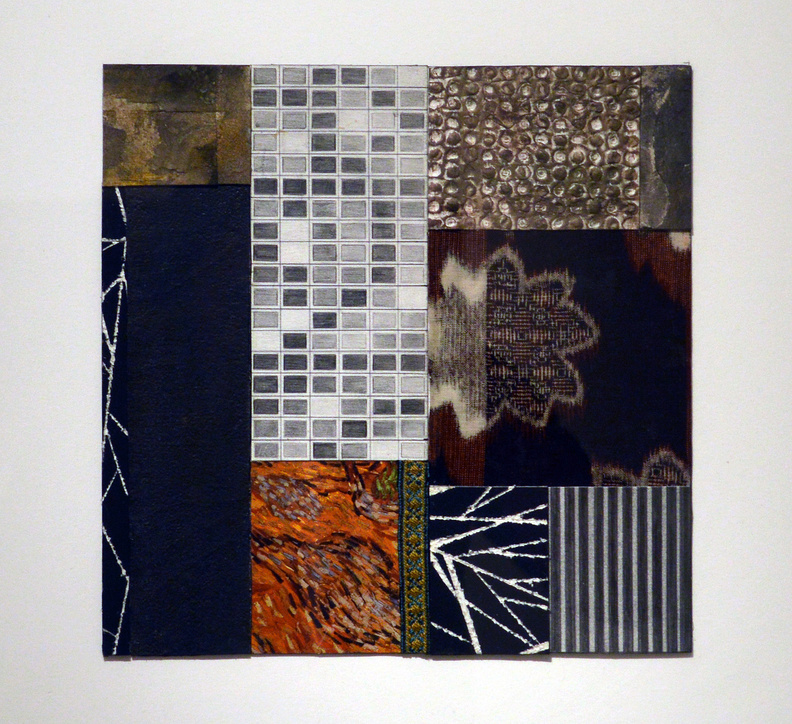

The collages are small, float-framed squares comprising elements of her drawings, paintings, constructions and personal effects such as remnants of her mother’s clothing.

As compositions, the collages are beautiful and sophisticated. This isn’t surprising, given that their components are elegant and highly refined, whether they are the artist’s musically geometric drawings or the finely textured skins of her deconstructed wall pieces.

Moreover, her late mother’s Japanese fabrics are far finer than anything we commonly see in America in terms of weave and design.

The collages don’t distill down into precious entities. Rather, they open up like cross-sections of something rich, ever-flowing and expansive (think glass murrini). They aren’t containers, but doors to other worlds. A bit of a drawing, for example, is handsome, but it pushes your mind outward to the broadest sense of Sakanishi’s drawings (think synecdoche).

A tiny fragment of a Van Gogh print must have personal meaning to be included, so it makes Sakanishi resemble us as passionate consumers of visual art. That fragment inspires calendar logic — it marks the past and our valued connections to it.

History, Sakanishi hints, helps form what we look like as well as how we see.

Her use of incredible fabric as collage bits (“pasta” — to follow the Italian “murrini” metaphor) acts something like a gender-specific fork in the road. Some viewers will immediately empathize with the repurposing of the beautiful old dresses, while others would be uncomfortable with that idea (possibly preferring complete artifacts). In other words, where some see scrap, others see scrapbooks.

Through the facets of texture and color, Sakanishi presents her mosaic aesthetic sensibility. We don’t need to know the specific references or her private details — and with our cultural sense of privacy, we don’t want to. It’s enough to sense the distinct and fully refined elements of an integrated person.

Sakanishi (or rather, her “author function”) comes across as whole and appealing rather than wistfully nostalgic through her collages. Her distilling of various elements into a multifaceted whole is a deeply American approach.

Moreover, postmodernism has a conflicted relationship with collage: Collage was invented as part of Cubism; yet it’s more “postmodern” than anything invented by the postmodernists.

This mirrors Sakanishi’s “Japanese question”: It’s not who she is, but rather just part of the patchwork quilt she has — by choice — become.

Sakanishi’s constructions are a very different story. Instead of being about who she is, they are about what she does. They seek to stand alone with the viewer’s experience of them — coolly free of any autobiographical reference.

The constructions are about independent systems rather than fixed points. “Close Up,” for example, begins with a circle in a square (itself a trope), which has a light gray complementary square next to it, in which the cut-out, dark-gray circle leans up against the first square — subverting symmetry by illustrating the force that connects the forms, like a self-aware domino giving in to the force of associative gravity.

The domino theme is important — not as children’s tipping toys but rather as the back-and-forth tactical math game. Sakanishi’s constructions even look like so many gray dominos, spreading their game theory systems on the gallery walls.

Sakanishi’s intuition is that elements of systems define each other with a historical sense as well as progressive motion.

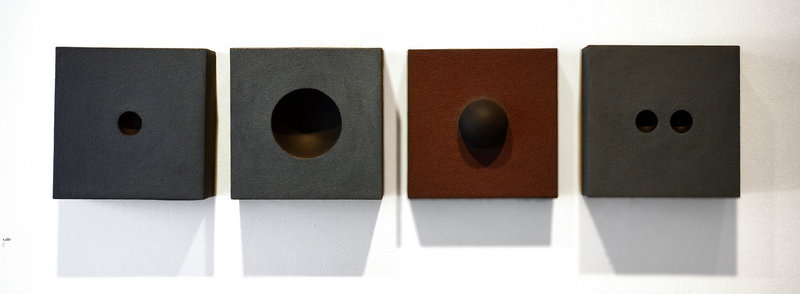

We can see this in her “New Orbit,” which comprises four square boxes in a row from left to right. The cool-gray first has a small semi-spherical cavity in its center; the next, a larger one. The next is shallower, but with a semi-spherical bulge. Each is a response to the previous element — until the fourth, which features a pair of the small cavities.

Only with the final piece does the whole thing fold back on itself and divide into two pairs: The middle complementary pair and the bookending start/finish pairs.

In some ways, “New Orbit” is a model of the creative process. A response to a first term begins a system in search of punctuating completion.

“Comfort Zone” places a Malevich/minimalist square in the center of its support, but darker segments on the left and bottom edges converge to a punctuating square in the lower left.

This piece caught me looking first to find either the Western left/right, top/bottom logic or then the Japanese bottom/top, right/left logic. But it’s an x,y grid with 0,0 in the lower left. Geometry, Sakanishi reminds us, is another kind of system altogether.

While Sakanishi’s constructions feel intellectual, they are fundamentally intuitive and tightly bound to the logic of painterly formalism in which sensibility inevitably trumps logic — even when it acts like minimalism.

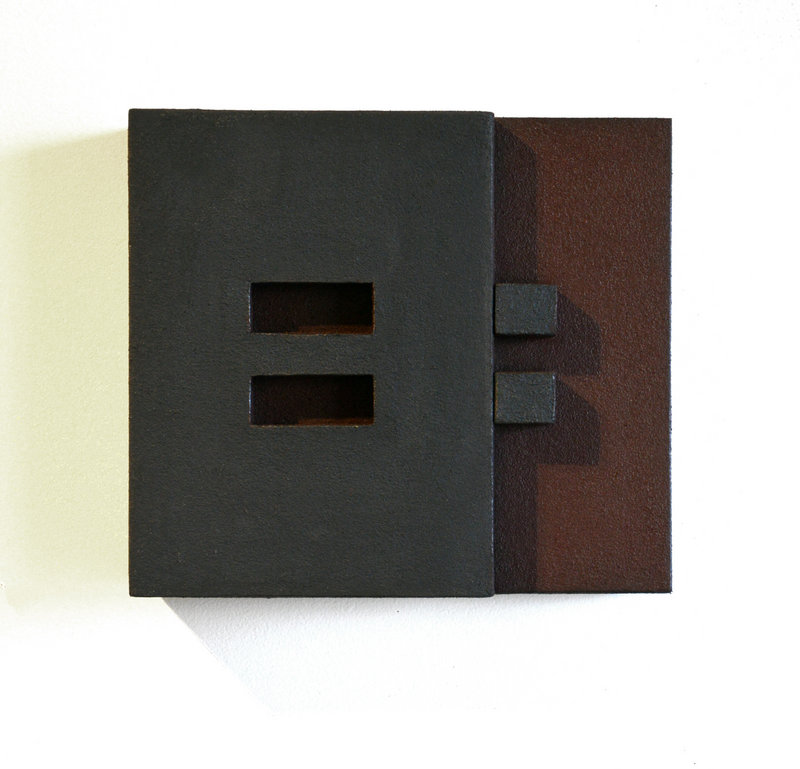

I love the smaller pieces, such as “Confidence,” in which an incised “=” is tentatively echoed by its positive (and, again, left-pulling) complement.

But I think the larger pieces, such as “Sentinel” or “Moment in Time,” lose the satisfying gestalt of the smaller works. They become prickly cold paintings rather than balanced objects. They get fussier and more technical, and lose their sense of human intuition. Then again, it’s interesting to see what sprawl does to her work.

Having shown with June Fitzpatrick for more than 20 years, Sakanishi has long been one of my favorite Maine artists. “Confluence” only reinforces that opinion.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.