Last fall, I noted in these pages that Avy Claire’s tree pictures made of words transcribed from the radio did more to spell out the real time of their making than any other drawings I had ever seen. In the context of a group show, it’s actually quite an accomplishment to convey that kind of conceptual content with such clarity.

The consistent element of Claire’s work has been her writing-like mark-making; her trees of previous shows were rendered by meandering lines of cursive script.

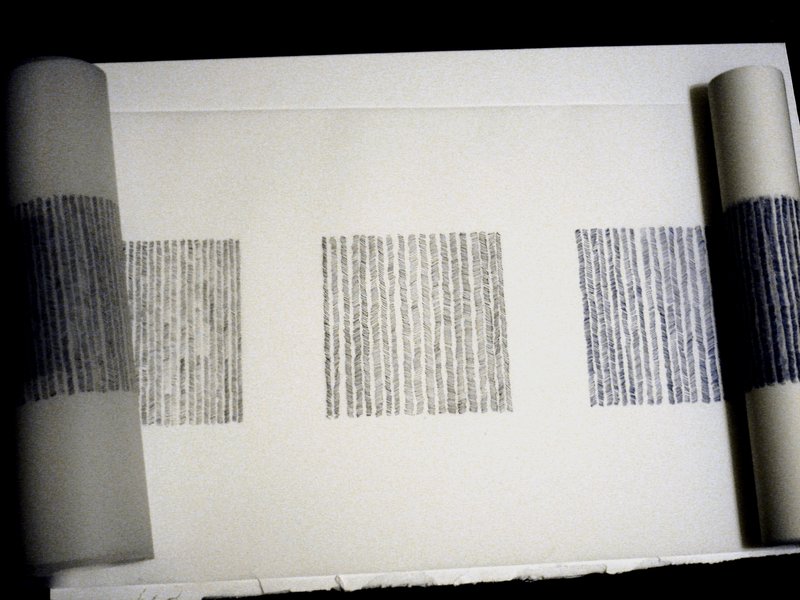

Her new work is different insofar as it looks more like minimalist grids (the standard bearer for intellectually intimidating contemporary art), but it is nonetheless consistent by means of the compulsively temporal rhythms of flickering hatching or scribbled script.

Claire even encapsulates her work in unwavering terms. In the statement for her current solo show at June Fitzpatrick Gallery in Portland, she notes: “In 2003 I began drawing in such a way that it became clear to me I was marking time.”

I think we put too much stock in such clever sound bites. When they feel like they hit the mark, we tend to nod in knowing agreement and move on. Problem solved. We got it.

But explanations can only prepare us for experience — not deliver it. That treasure map, after all, might lead you to where X marks the spot, but you will still need your shovel.

What does it mean to spell out the artist’s process in real time? Does artistic process translate directly into meaningful content in this case?

These two questions might be all you need to bring in order to appreciate the conceptual heft of “Marking Time.” However, if you don’t articulate such questions or you don’t tend to see art in terms of self-consciously experiential terms, Claire’s work could strike you as frustratingly stark.

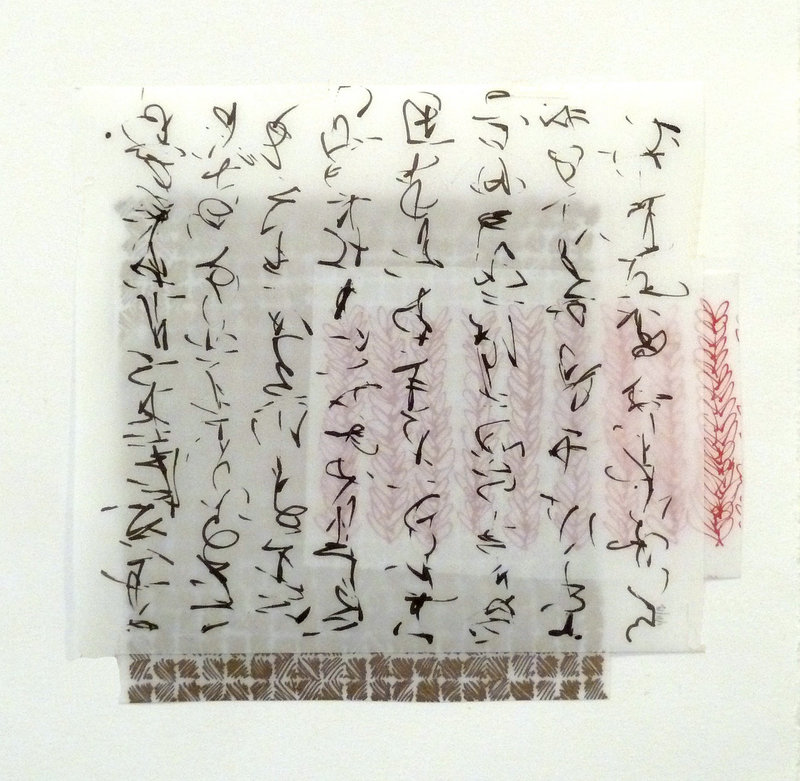

“12.01.14,” for example, comprises three sheets of frosted but transparent Mylar, each marked in columns or a grid with a different color of ink. The bottom layer features a parquet grid of taupe hatch marks — diagonally striated squares that produce diamond forms.

Over that is a small, horizontal sheet with nine wheat-like columns of climbing red loops. Over these two is a more open sheet with eight calligraphic columns of what look like (but aren’t) Chinese characters or Japanese katakana.

Just looking at such work is extremely complicated. Do you start with the bottom sheet or the top? The wheat-like images seem to grow from bottom to top, and are only uncovered at the right (punctuation or the starting point?) The parquet hatching is only completely visible at the bottom of the group. And the calligraphic characters mimic a language that is read from right to left and bottom to top.

This sounds consistent and coherent, but it feels oddly over-determined to take on our inclination to read from left to right.

Moreover, Claire is essentially forcing us to see her process as reading back over time — which is quite different from flowing with a narrative. It strikes me that she is trying to mark her own labor not only as material memory, but in historical terms. In fact, I would say she is even seeking to put her own work in art historical terms with her obsessive inclusion of so many archeological data points. This could easily be taken as narcissistic self-involvement, as though Claire sees herself as a historical great.

But her metaphorical depth, as subtle and quiet as it is, is consistent enough and sufficiently focused on process to make it clear that she is interested in relating the artistic process of mark-making to labor, personal experience, memory and historical narrative. And while her pieces might first strike the viewer as intellectually reserved, together they create an insistently powerful image of an individual person with quirky obsessions and a desire to order her productive libidinal impulses.

In Freudian terms, you could say Claire’s new works are like abstract versions of the “talking cure.” In fact, her dozens of tiny “Point and Line to Plane” drawings hint at psychoanalytic logic: Tiny marks on their own mean nothing, but together, they form lines, patterns and clusters, and from there, spatial plateaus.

Context, in other words, is everything. This is where Claire’s work leans back toward the philosophical. Time, after all, is only the marker of difference. Letters only get meanings as words. Words get meanings in sentences — and so on.

A dot means nothing. But a dot a day becomes a calendar. Scribbles in columns become stand-ins for texts; they deliver the very notion of narrative in abstract drawing.

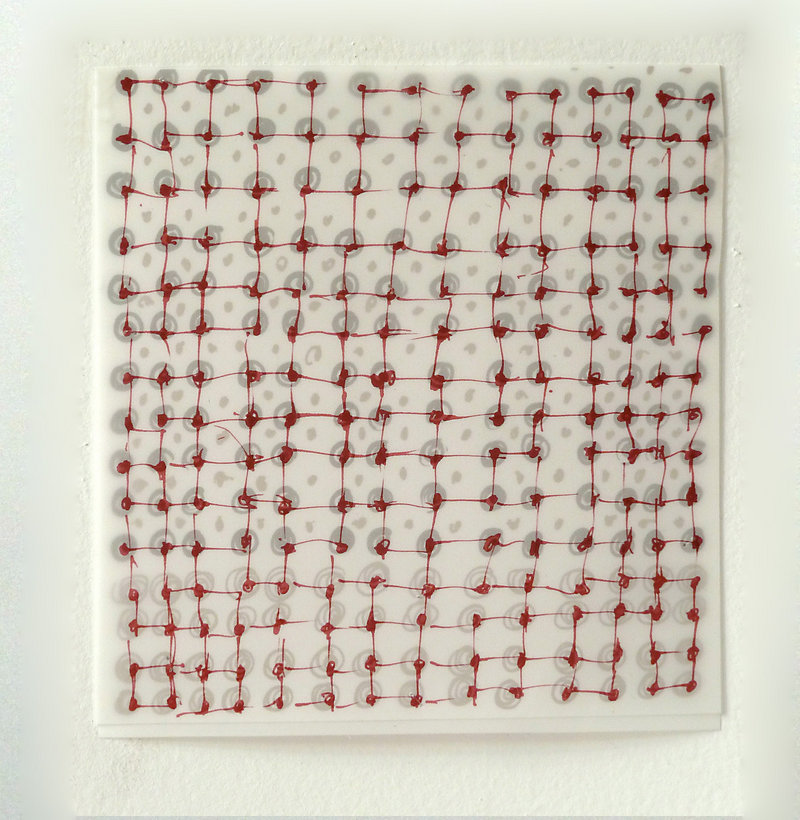

I particularly like “12.01.12.” in which Claire sews two sheets of her elegant scrawl together with red thread (not by chance the stuff of books). In this work, we see the artist’s hand, the narrative as thread, the marks as labor, the flow of time, the cross-pollination of ideas/texts and so much more.

I think Claire’s work is too elusive for the typical art viewer to comfortably enjoy. But if liminal conceptualism or process-oriented drawing is your cup of tea, you could well find her heady brew deliciously sophisticated.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be reached at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.