When Markham Starr heard that America’s last sardine cannery, located in Prospect Harbor, was closing, he knew he had to go there.

Not that sardines are his favorite snack or anything.

Starr is a photographer fascinated with documenting working waterfronts and other industries that are getting more scarce these days. The sardine canning industry had flourished in Maine and had virtually built the town of Eastport, but now the last cannery was closing. The work was moving to Canada.

In spring 2010, Starr drove to the former Stinson cannery (which, at that point, was owned by Bumble Bee), and spent a few days taking about 1,000 photographs of the plant’s 128 employees as well as every step of the canning process.

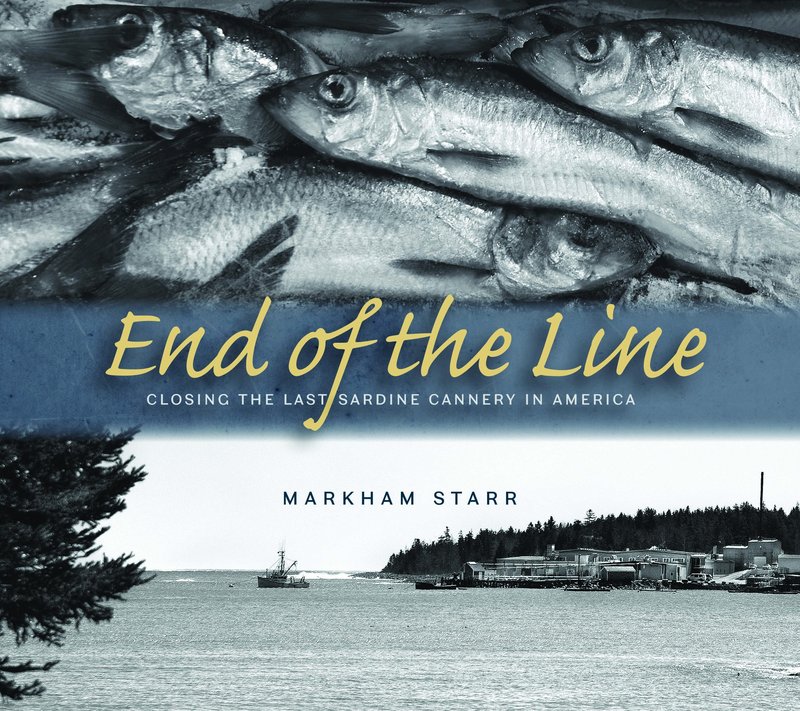

The result is the new black-and-white photo book “End of the Line: Closing the Last Sardine Cannery in America” ($24.95, Wesleyan University Press). Starr, 54, lives in North Stonington, Conn.

Q: How did you decide to take pictures at the cannery?

A: I heard about the closing on NPR, and I thought, “Boy, that’s the end of an era.” So I drove up there, seven hours, and talked to the manager. I then had to go home and write a proposal to Bumble Bee.

A couple weeks later, I got a call and they said they were allowing me and a few others to go in, and they were giving us a couple days to take pictures. They told us they didn’t want us to bother the staff, because they had work to finish up before closing. So I didn’t get a chance to do (in-depth) interviews.

Q: How did you decide to put these pictures in a book?

A: Originally, I just wanted to react quickly and get 1,000 images of the process, from beginning to end. I took them for posterity. I didn’t really have any intention of doing a book, but then I just happened to be talking to Wesleyan University Press about something else, and they wanted to do the book.

Q: What were some of things that struck you when you first saw the inside of the cannery?

A: It looked like a real working Down East factory. There was nothing spit and polish about it. The offices were just rooms with a phone and a desk and file cabinets. So it struck me that this was a very hard-working place that produced an awful lot of material, and there were absolutely no frills. It wasn’t like they were wasting money.

Q: What were some of the interesting things you learned about workers?

A: It was not uncommon to find people who had worked there 10, or 30, or 50 years. A lot of them were devoted to the original owner (Stinson) and stayed on. One (older) man had been told that as long as he could crawl through the door, he had a job. So there was a real dedication.

And putting the fish in cans was done all by hand, by 20 women working in teams of two. The two fastest women could pack 10,000 cans a day, each. It took years to figure out which women worked best together, which was important, because they got paid by the case. These women took a lot of pride in what they were able to do.

Q: Did it smell very fishy in there?

A: No, not really. It smelled like cooked fish, because the fish had to be steamed to get out the oils, and cooked to be canned. And even though they went through thousands of tons of fish, the place was spotless.

The big thing in the factory was noise. The sardines were packed in aluminum cans that were shot around the factory by air and conveyor, so you heard banging all day long. And it was pretty hot in there too, because of all the steam.

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Twitter: RayRouthierW

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.