If the reader is anything like this baby boomer, he or she will find it impossible to calculate the number of hours spent watching television or movie Westerns.

From playing cowboys and Indians as children in imitation of Hopalong Cassidy or Annie Oakley, to watching John Wayne or Barbara Stanwyck on the big screen (and as we matured, Clint Eastwood and Dan George), the imagined West has been an ingrained part of our lives.

Watching such films proved enjoyable for some, a guilty pleasure for others or a target for the politically correct crowd. Western film study has also become an academic field in itself.

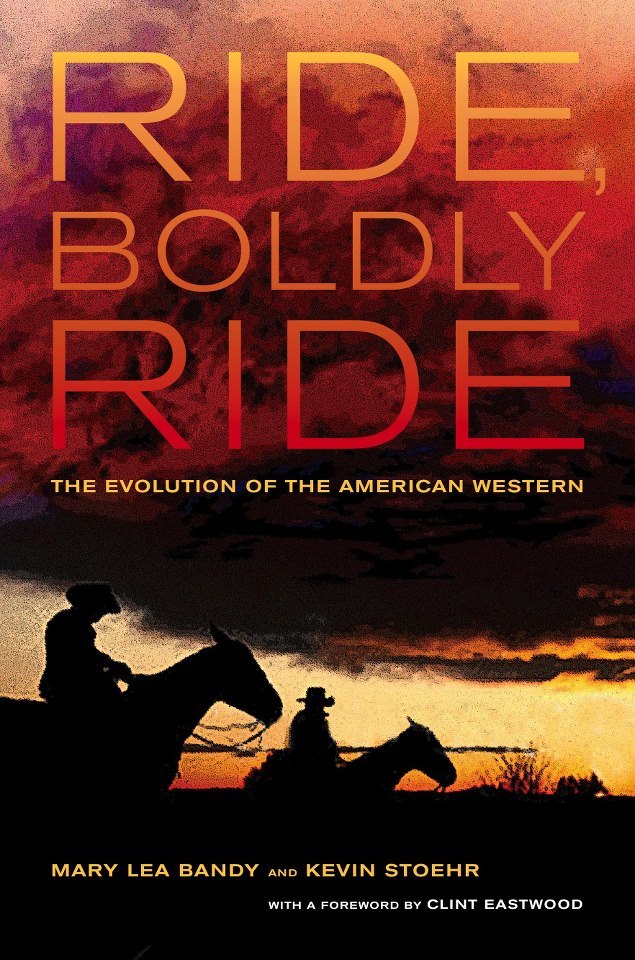

It is appropriate that Eastwood, an actor-director who has done so much to shape the genre, wrote the introduction to the first truly sweeping, fact-filled survey of the subject, “Ride, Boldly Ride: The Evolution of the American Western.”

The book’s authors, Mary Lea Bandy of New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Kevin Stoehr of Boston University, are top scholars who know their materials the way literary historians or critics might absorb Elizabethan theater or American Transcendentalism. However, they are also movie fans, which warms the tempo of the text.

They love the stuff, and this is the very stuff of American history and myth. Cowboy films began with Edison on the East Coast in the 19th century, but quickly moved to sunny Western climes. The actors, including William S. Hart and John Big Tree, came right out of the “real West” into the “reel West.”

Such flickers linked back to the “leatherstocking” novels of James Fenimore Cooper and the landscape paintings of Thomas Cole and Albert Bierstadt, then evolved into recent cinema, such as “No Country for Old Men” and “There Will be Blood.”

This is the territory of laconic heroes; stark or spectacular landscapes; good vs. evil; loyalty, love and hate; civilization and savagery; the common man vs. big business.

The book is both encyclopedic and a page turner, which is almost impossible to accomplish.

And there are huge and sustaining roles played by Mainers, starting with the Hollywood arrival of Portland-born actor-director Francis Ford in 1911.

The authors call Francis’ kid brother John, director of six Academy Award-winning films, “the great master of American Western film,” and he is the subject of large portions of “Ride, Boldly Ride.”

The reader discovers that “Northwest Passage” (1940), not generally considered a true Western, was written by Kennebunkport’s Kenneth Roberts and that “The Ox-Bow Incident” (1943) was based on a novel by Walter Van Tilburg Clark of East Orrington.

One can make many more connections, including Jean Arthur, the Farnum Brothers, Molly Spotted Elk, and Paramount and United Artist president Hiram Abram.

The book’s 11 chapters cover about every angle, from silent Westerns on up to “Cowboys and Aliens” (2011). But I am sure every fan will have their addition or rebuttal.

In “Women Against the Frontier,” a moving chapter centered on actress Lillian Gish in “The Wind” (1928), for example, I was disappointed to find no discussion of 1979’s “Heartland” with Conchata Ferrell, a stunningly true Western if there ever was one. But this is a small point, and you can’t mention everything.

“Ride, Boldly Ride” informs, engages and entertains as few books can.

William David Barry is a local historian who has authored/co-authored seven books, including “Maine: The Wilder Side of New England” and “Deering: A Social and Architectural History.” He lives in Portland.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.