WATERVILLE – As usual, the Colby College Museum of Art has a bunch of great shows on display. Between its scale, collections and accessibility, I think Colby is currently Maine’s greatest champion of visual arts. And it’s hard to compete with the fact that Colby is always free to the public.

There was a busload of schoolchildren at the museum when I was there last week — hardly unusual for a museum. What distinguishes Colby, however, is that those kids can come back with their parents whenever they want — no parking meters and free admission.

The students were at the museum primarily to see a show of photographs by Clemens Kalischer (born in 1921) depicting World War II refugees waiting for immigration processing in New York City in 1947-48.

It’s simply a great show. The images are strong, the scenes are interesting, the prints are of terrific quality, and the subject is of fundamental importance to American cultural history.

“Displaced Persons” is one of the most moving exhibitions I have seen in years. Four of the 19 images depict people hugging or kissing, and marking a sort of personal conclusion to what was one of the most horrific odysseys of Western history.

One shows an old woman clutching a man whose face is buried in her neck. The gnarled grip of her hand on his shoulder is in a different realm from the iconic sailor dipping a pretty nurse for a stolen kiss in celebration of the end of the war: the end of missing a loved one in mortal peril as opposed to a moment of exuberant relief.

Another image seems to show a mother embracing her son. Her hair is swept back in the fashion of the day, and she holds a hand up to his cheek — his dirty cheek under unkempt hair. His fingers are filthy sausages around her back. His smile is exhausted but gracious, and her face reveals an emotion for which we don’t have a word: a combination of relief, love, the parting of doubt and tearful joy — but, oh, the joy!

Another image shows an embracing couple so lost in each other they have created their own sovereign space. She stands upright in her dark suit and fashionable hat while he bends to clasp his hands as firmly as possible around her back and bury his face in hers — his fedora blocks their faces from ours. They could be kissing or whispering their love or sobbing. Whatever might have been the case, it was their moment.

Assembled from the amazing Lunder Collection, the Kalischer images are sure-handed but sympathetic. They are peopled with Jewish refugees arriving from Germany, exhausted from being pushed beyond what any normal person should have to bear.

But the pictures are just as much great photographs as great images of people in extraordinary circumstances. They are beautifully printed. Their compositions are strong enough to clearly echo the work of the great social photographer Lewis Hine, but Kalischer has a way of using the forms of the individual’s clothing and fashion to imbue the works with unexpected jolts of visual and cultural sophistication.

A particularly excellent photo shows a beautiful young woman slumped on a staircase. Oddly (to us), she’s holding a complete fox fur, so she may be well enough off, but she seems to be the very image of hopeless fatigue — until you move in close to realize her eyes aren’t closed but rather fixed on the ring on her left hand. The tiniest flicker of hope, it seems, can change everything.

My favorite Kalischer is an image of two young girls whose noses are maybe an inch apart and their hands even closer. They are electric with happiness. One talks quickly, and the other looks like she’s about to explode with gleeful excitement.

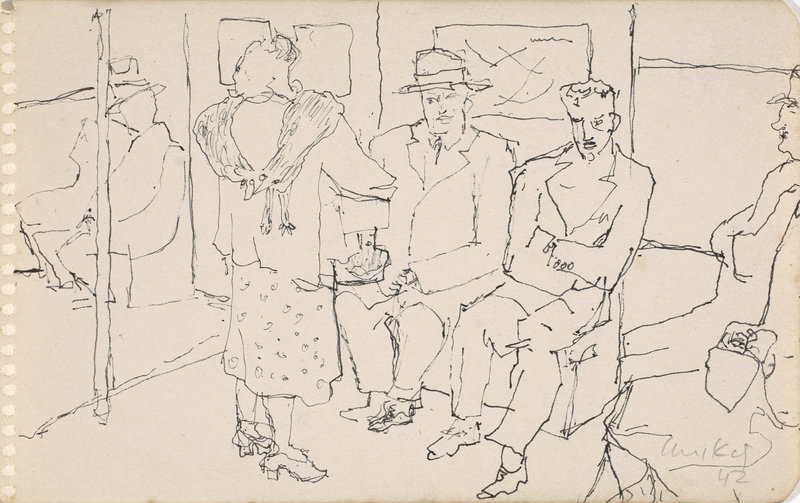

In another part of the museum is an exhibition of drawings by Alex Katz that includes eight sketches that Katz (who is also Jewish) did on the New York City subways during the same years Kalischer was photographing the refugees.

I am intrigued by one in which a lady wearing a fox fur stands while a man in a fedora hat and a self-involved youth sit in front of her. (I thought those were the good ol’ days when men would offer their seats to a woman).

These really were the same people (probably not literally) that Kalischer depicted in his photographs, but Katz’s loose (and probably train-jostled) hand has a surprisingly contemporary feel. These aren’t particularly strong drawings, but with Kalischer in mind, they are surprisingly effervescent.

Katz’s apparent psychological disengagement from his subjects in the pencil drawings he made in the 1980s is in striking contrast to Kalischer’s warmth. But maybe what Katz has denied is not psychology but mood.

Katz’s pictures reject nostalgia for the broader perception of life in the here and now. Their faces might be cool, but their gnarled hands embrace the continuum of humanity rather than any fleeting moment.

Katz’s drawings are a bright spot in Colby’s 10 current shows, but the Kalischer is not to be missed.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.