There is an exhibition of African-American book illustrators at the Museum of African Culture in Portland that includes multiple winners — all Mainers — of the prestigious Coretta Scott King Award.

“Lines Converge, Colors Dance” is particularly interesting not only because it puts the work in a context of African roots, but because it puts local artist and MECA professor Daniel Minter on the national stage that he has earned as an illustrator.

Minter now seems to be everywhere. He’s also featured in “Go Figure” at Greenhut Galleries in Portland and with an installation at Portland Trading Co. He was featured in Bruce Brown’s print extravaganza “Breaking Boundaries” at the Portland Public Library earlier this year, and he has been in the news because of his Coretta Scott King Award.

“Mere illustration” is the kind of phrase that you might hear across post-war America to degrade this mode of art, but I think it’s a mistake on the level of Mainers’ betrayal of watercolor. (In the land of Marin, Homer, Hopper, the Wyeths and so many others, we — friends, Mainers, countrymen — should not come to bury watercolor, but to praise it.)

Until landscape painting took serious hold in France in the 19th century, painting — led by religious and history painting — was primarily in the service of illustration. (The major exception, though partial, was portraiture.) For centuries, the Church maintained absolute cultural hegemony, and art’s purpose was to illuminate the Bible.

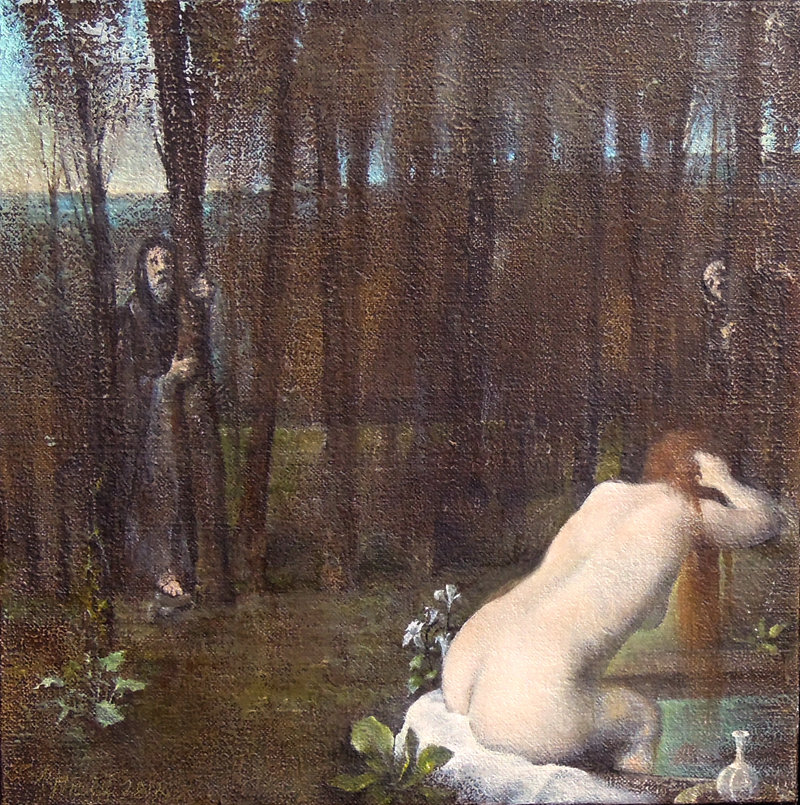

The echoes of religious art in contemporary painting are so omnipresent, they practically camouflage themselves. My favorite piece in “Go Figure,” for example, is Joseph Nicoletti’s “Susanna at the Baths,” the Old Testament story in which the religious elders come upon the beautiful Susanna (Hebrew for “lily”) bathing in her own yard.

Only this time, she’s a recognizable Degas nude, so the encounter is between an older mentality (reactionary and bullying) and modern art (shocking and attractive, but pure and virtuous nonetheless).

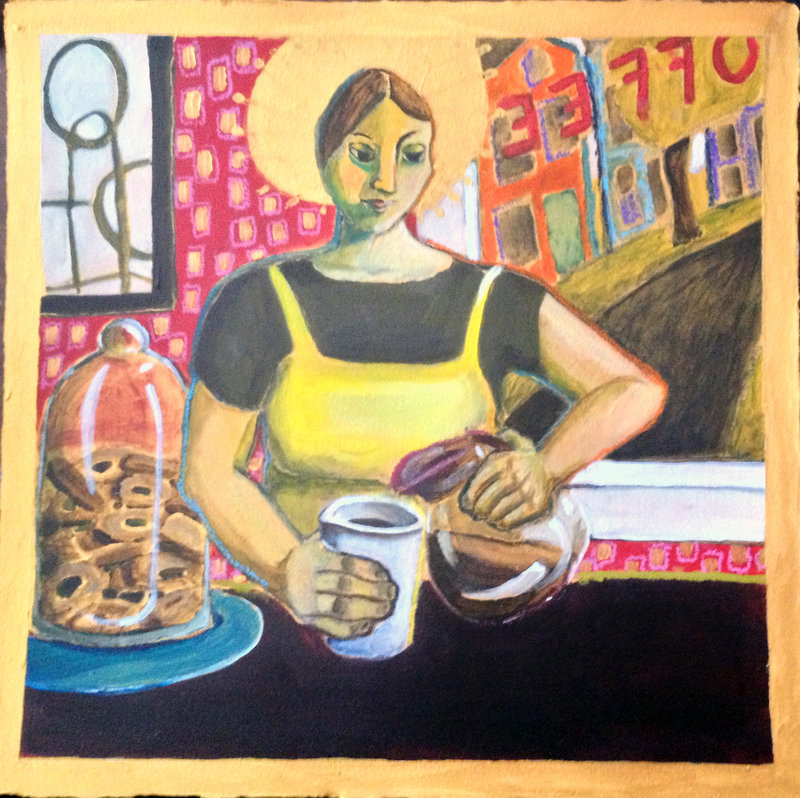

A more common reference, illustrated by Allison Goodwin’s haloed barista, ties the shows together. The joke about worshiping at the morning altar of coffee seems obvious, but the reference is art historical rather than religious per se.

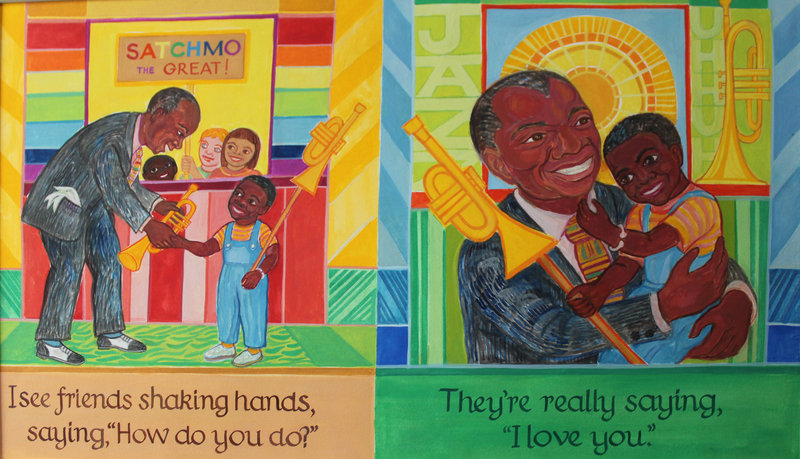

At the Museum of African Art, Ashley Bryan, a true pioneer of African-American children’s books who lives on Islesboro, matches the logic with a picture of Louis Armstrong holding a toddler in classic Madonna and child form, with a halo sun between them.

The Madonna and child genre opens the door to syncretistic imagery in African art, as the figures are also featured in a nearby 18th-century Ogbananjo spirit mask of the Igbo Tribe from what is now known as Nigeria. Comparing these two works opens the door on a fundamentally vast chapter of world history.

“Lines Converge, Colors Dance” is a handsome little show of 20 illustrations by Bryan, Minter and Portland-based Rohan Henry, whose drawings have a charming flare reminiscent of Antoine de Saint-Exupery of “The Little Prince” fame.

While Bryan’s 50-bird cut paper collage “Beautiful Blackbird” is the star of the show, Minter comes off as a particularly strong graphic artist with an edgy brilliance to his storytelling.

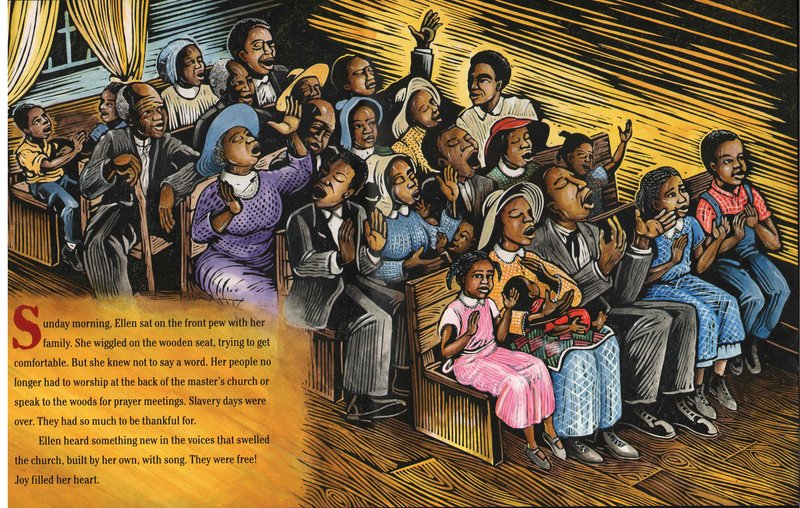

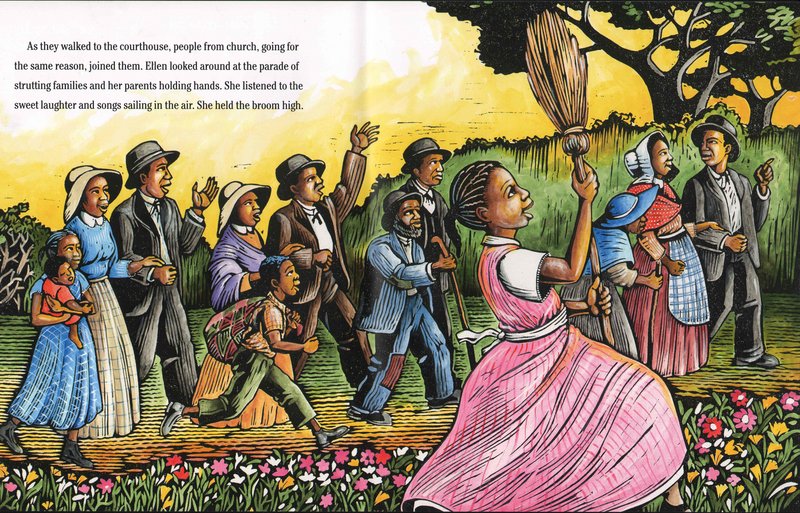

The images from “Ellen’s Broom,” for example, depict an Emancipation-era girl whose family, for the first time, can attend their own church. But her broom is a totem from a time when, by law, the Christian sacrament of marriage was denied to slaves.

Ellen’s broom explodes with meaning as our society grapples with denying gays the civil right of marriage. While “jumping the broom” was a wedding for some, it was a symbol of witchcraft and fear for others. Minter taps this topic with undeniable (though subtly subversive) power.

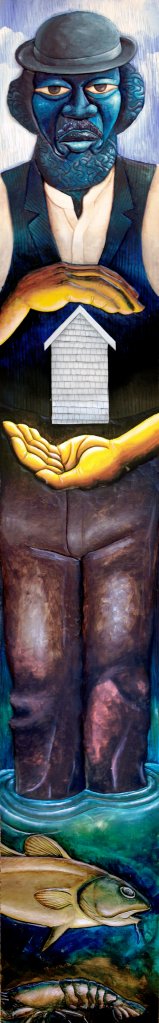

Minter’s most meaningful work as a Maine artist, however, is at Greenhut: “Malaga Man,” a tall, narrow, wooden low-relief painting of an African-descended man from one of Maine’s most shameful chapters. (Malaga Island was home to a post-Emancipation interracial community evicted in 1912; the men, women and children were forcibly abducted from their families to erase their identities. To destroy the community, even the graves were exhumed.)

Painted in a primitivist style, the Malaga man’s almond-shaped eyes unblinkingly meet yours. He stands ankle deep in water over a cod and lobster, clearly identifying the place as Maine. Over his heart floats the image of his home — a simple shack — which reflects sacred glowing light on his hands that encircle the home.

This hands-around-heart gesture is repeated in a trio of Minter’s canvases based on a repeated frontal form of a girl in a dress whose African-featured face is presented in complete profile. Together, these comprise a very successful group that reveals the artist’s concerns between what is repeated and the myriad symbolic variations amongst them.

Sun and moon, bows and arrows, mirrored images, bones, the ocean, death, boats, a lily (“Susanna”), shacks, birds and so much more create a powerfully rich world of syncretistic symbolism ranging among the natural, tribal and Christian worlds of the African-American experience.

The apparently simple primitivism of Minter quickly fades behind his painterly talent and, in particular, his virtuoso quality of gossamer line.

“Lines converge” and “Go Figure” are both solid. But together, they are particularly fascinating.

As an important Maine artist, Daniel Minter has arrived.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.