The Center for Maine Contemporary Art’s “MENTOR: 40 Photographers/40 Years” is an exhibition featuring master photographers from the Maine Media Workshops & College and their students — many of whom in turn have become leading American artists.

Organized by CMCA curator emeritus Bruce Brown, MMW professor Brenton Hamilton and CMCA director Suzette McAvoy, this impressive show is likely to change the way you think about photography in Maine. But “Mentor” goes beyond photography to inspire thinking about artistic culture and education.

Maine became one of the nation’s leading centers for art in part because this was a place dominated by nature rather than nurtured culture.

In fact, more than anywhere, Maine came to fit the very model for American art: Rather than the conversational cafe culture of Paris or New York, Americans have long imagined the artist heading off on his own to struggle in the spiritual and intellectual wilderness on his quest to create something authentically self-won and genuinely original.

We like to think of American art as something beyond culture’s current clutches: The cutting edge still unfettered by affect.

Yet — very quietly — Maine has taken a leading role in professional-level arts education. Although virtually invisible to the locals, Haystack and Watershed have international reputations as centers for fine craft; the Maine Center for Furniture Craftsmanship has likewise been soaring upward for two decades; and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture offers arguably the most important and prestigious art residency in America.

And let’s not forget MECA and Maine’s great liberal arts colleges; they are fountains of cultural leadership — professional as well as academic.

And once you see “Mentor,” you will not leave MMW off the list.

To begin, “Mentor” is loaded with fantastic photographs. This is important because while the signage tips its hat to MMW, there is not much clear information about who taught whom. This actually might be a good thing since it puts the viewer in that art history generational-trajectory frame of mind (think Perugino/Raphael, Thomas Hart Benton/Jackson Pollock, etc) without over-determining any relationships within the work.

Because “Mentor” is more about excellence than specific aesthetic sinews, I am talking here more about context than specific works, but prepare to be impressed by the work: Ernst Haas (1921 — 1986), for example, was one of America’s most respected photographers and his 1961 large-scale silver print of a brooding, silhouetted figure (Wright?) on an upper tier of the Guggenheim Museum makes a clear case why. The similarly-renowned Joyce Tenneson’s large, iconic print of a gauze-clad, almond-eyed young woman with white doves on her shoulders is so gorgeously seductive as to be unnerving. (Even if you don’t recognize Tenneson’s name, you undoubtedly have seen her photos on the covers of publications like Time, Life or Newsweek.)

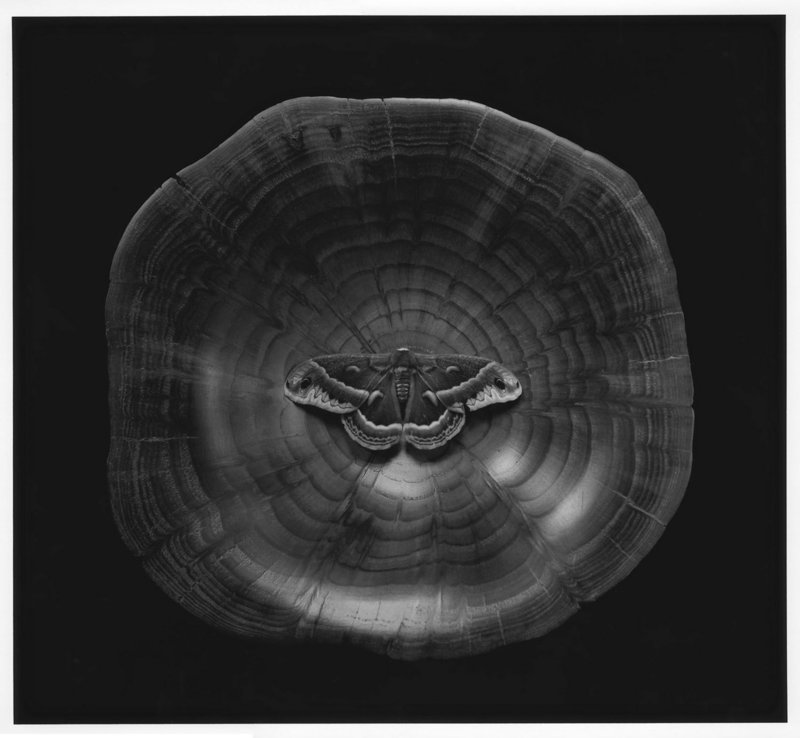

Much of the strongest work is by photographers we recognize — such Paul Caponigro’s stunning butterfly in a wooden bowl (2008) or Arnold Newman’s silver print portraits of Zero Mostel (1962) and Truman Capote (1977).

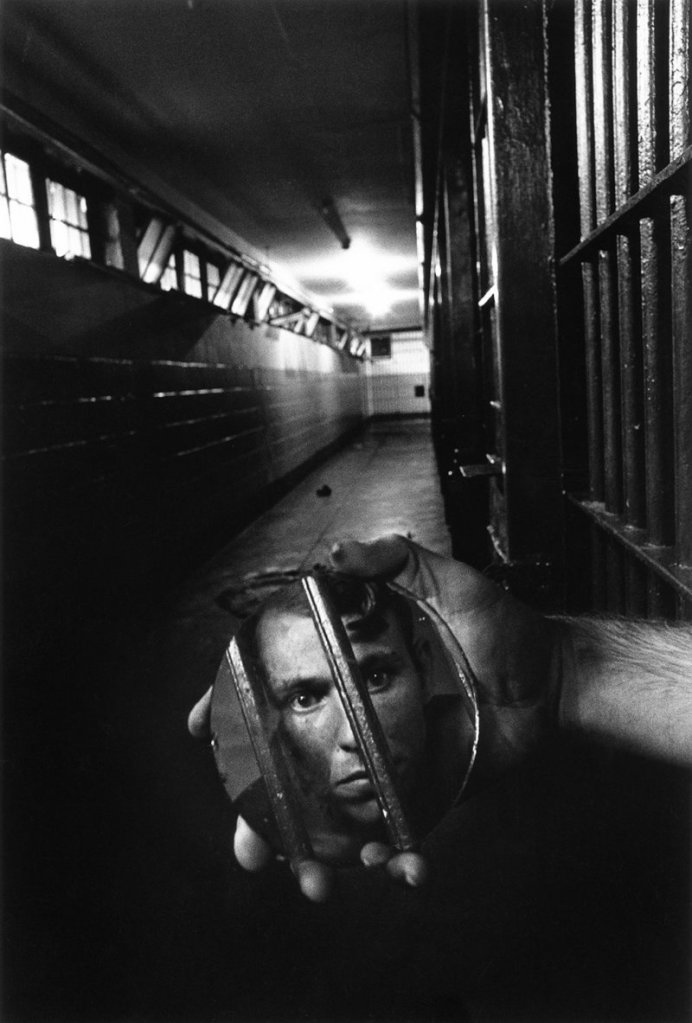

My favorite discovery was Sean Kernan’s startling 1977 “Prisoner with Mirror”: we see the prisoner’s grim, chiseled face as a portrait in the small round mirror he holds out between the bars of his cell).

There is excellence in color, too, including Cig Harvey’s 2012 c-print, “The Pomegranate Seeds, Scout” featuring a child ducking down in a crimson chair before a crimson wall under a wizened gray plank table covered with crimson seeds.

And then, everywhere it seems, there is magic: Susan Hayre captures an acrobatically impressive little goat on the downside of an epic leap; Jay Gould’s mysterious panorama leaves us alone in the forest with the smoke column of a magician’s disappearance; Arno Minkkinen’s image of a woman’s crossed arms jutting up through the snow is a paroxysm of creepiness.

Despite the strength of “Mentor,” the most entertaining show at CMCA is Caleb Charland’s ironically-titled “From the Basement to the Backyard” (it’s in the basement). Charland’s pictures also revel in the everyday magic.

In his “Fruit Battery Still Life (Citrus),” Charland redeploys the classroom trick of generating electricity by putting a galvanized nail into one side of a potato and copper wire into the other; in this case, the bags of limes, lemons and oranges gather to light an overtly-unplugged lamp while they pose handsomely like a Dutch Master still-life.

Charland’s fruit battery shots such as apples in the orchard are joined by other theatrically fascinating images: a comet-like burning tennis ball; drops of water in a jar of oil; a time-lapsed bouncing pen light; a sculpturally brilliant display of magnetism featuring gravity-defying nails, string and a wooden box. Charland crosses the line to compelling art through his concurrent commitments to aesthetics, craftsmanship and photographic technique.

Charland’s work also created a scintillating context for a CMCA-hosted (and decidedly unscintillating) talk by New Republic art critic Jed Perl who is touring his new book “Magicians and Charlatans.” While Perl’s no-school-like-the-old-school elitism purports to champion artists who create parallel universes (“magicians”) against the charlatan art-market-manipulators like Gerhard Richter or Andy Warhol, Charland’s sparky work contraindicates Perl’s snobby notions that the masses don’t like, understand or value art of genuinely passionate imagination.

But whatever fascinations or trepidations we hold for the photographic sleight of hand, CMCA’s “Mentor” and MMW’s accomplishments are both impressively real.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.