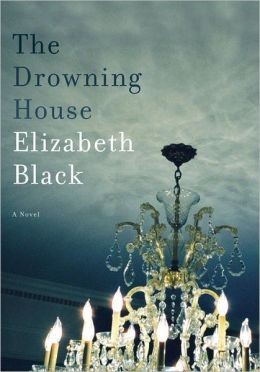

Houston resident Elizabeth Black makes a notable debut with “The Drowning House,” a multigenerational, thrillingly evocative and witty novel that spans the decades between the devastating 1900 Galveston hurricane and the island circa 1990.

Black amusingly elicits Texas from the first page: “I knew I was in Texas when I swerved to avoid a shape by the side of the road,” says protagonist Clare Porterfield, driving in from New York. “I stopped and backed up to confirm that the shape was a chest of drawers. I’d lived away long enough to find the sight incongruous.

“But it all came back to me at once, the things I’d seen abandoned at the side of the road in Texas. Not just on rural blacktops, but along the busiest superhighways — gut-ripped mattresses, clothing, suitcases, and once, a velvet rocking chair. It was what you might expect in a country at war — personal belongings strewn along the side of the road, or on the frontier, when travelers came this way as a last resort. In the days when ‘Gone to Texas’ meant you were desperate.”

That kind of observational and descriptive skill is a good part of what makes “The Drowning House” so engrossing.

Clare, a photographer, returns to Galveston, ostensibly to direct an art exhibition. In truth, she’s “gone to Texas” because she, too, is desperate — to get away from reminders of her child’s death and subsequently tortured marriage.

She describes Galveston as “a place where you could sometimes see the past running alongside the present,” even in her own home. Clare grew up in the historic Hayes-Giraud house, where the photos weren’t of her ancestors, but of those who built the place, and their possessions mingled uneasily with those of her family.

Two mysteries drive the story and interrupt Clare’s exhibit research, which has a distinctly minor role in the narrative. One is from 1900, when a young woman allegedly drowned in the historic Carraday house next door, caught by her long hair on a chandelier as the water rose and trapped her. The other is an incident from Clare’s teenage years that also involved a death, and her and her boyfriend’s hasty exile from the island.

Black excels at summoning the unique culture of Galveston, its tragic past and scruffy present, a town that easily could have been as important a shipping center as Houston or New Orleans till Mother Nature literally sank any hope of greatness. The author absorbingly draws out the isolationist, melancholy nature that the island’s inhabitants have cultivated over the past 100 years, suspicious of strangers but utterly dependent on the tourists who flock to Dickens on the Strand and other manufactured merriment.

Black’s only major misstep is in trying to stuff too much into one book, and in doing so, leaving a lot of strings either tangled or untied too late.

The relationship between Clare and her teenage boyfriend is frequently mentioned, teasing toward a significant reunion. Yet we don’t get to meet him till nearly the end of the book, and it’s a vexing letdown. The riddle of the drowned girl also builds to an unsatisfying conclusion.

Yet maybe that’s part of the point. In Galveston, things never turn out quite as one might expect or want, and enigmas tend to stay just that. The Spanish, after all, called it Malhado — “island of misfortune.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.