The Ogunquit Museum of American Art is undervalued. To be sure, it is beloved within the local region and happily supported by the community of artists — famous as well as emerging — who are familiar with its collections, grounds, exhibitions and offerings.

Now in its 58th season, the museum that was founded by painter and international avant-garde intellectual Henry Strater is better than ever, and features several worthy exhibitions.

For context, it makes sense to start with the small show of Strater’s earlier drawings and related figurative paintings, “Henry Strater: The Drawing Tradition.”

A pair of life drawings in particular reveal his excellent hand and observational skills. One is an impressively taut female torso; the other is a woman’s body as seen from behind, sitting on one knee with the other leg outstretched. The weight shift and gestural twist of this figure are masterful.

Strater was not only a pivotal figure in the Maine artistic community, he was also a friend and European companion of the likes of Ezra Pound and Ernest Hemingway.

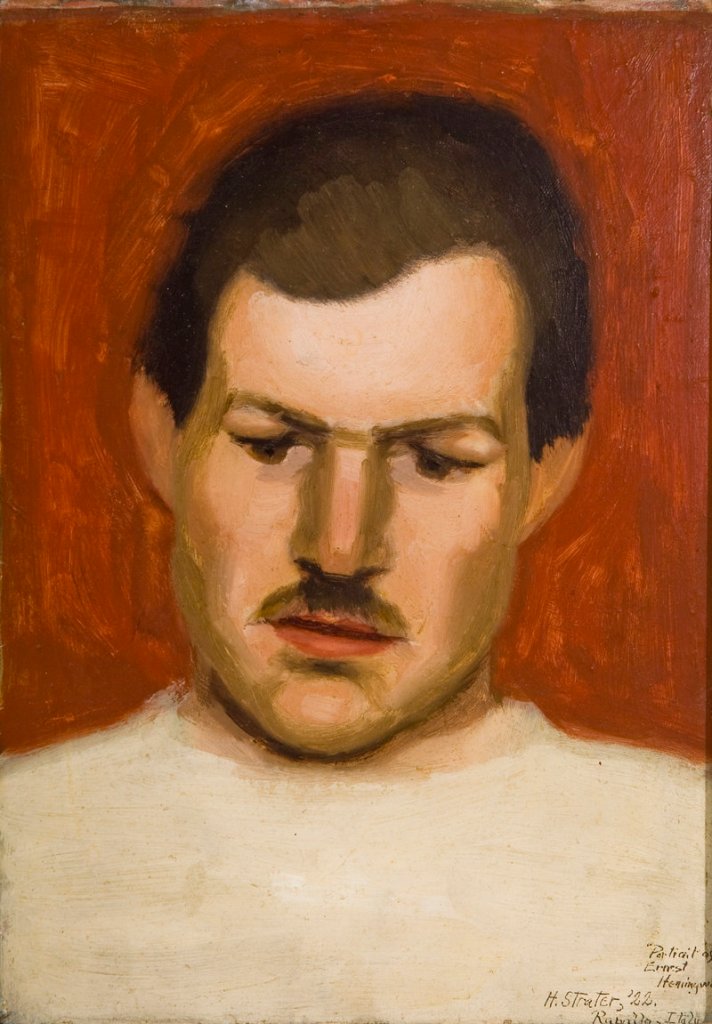

A pair of small portraits of Hemingway from 1922 is particularly revealing about Strater’s progress as an artist. One is an extremely realistic and calm view of Hemingway that the writer complained looked “too damn literary.” The other is a loose rendering known as the “Boxer Portrait” because it was painted soon after a morning match. The blocky, terse and bold strokes of the small painting match Hemingway’s prose with brutal accuracy.

Most striking is “Aronson to Aronson: The Lineage of Expressionism,” a brand-new show of works by David Aronson, his wife, Georgianna, and their son, Ben, the latter of which recently had a solo show at New York City’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

David Aronson’s sculpture is probably more impressive to our eyes now, but he was an important and accomplished painter. His muted “Teacher and Student” won a 1973 National Academy of Design medal.

It shows a young man soliloquizing before a younger man, who seems more rapt with his teacher than the book in his hands. In front of the teacher is another book that seems to be morphing into instruments, space or even cubist painting. It’s a quietly appealing and meditative canvas.

Aronson’s expressively figurative bronzes, however, are exquisite and impenetrably strong, as though armored enigmas. My favorite is the Pan-like “Angel with Flute,” which thrusts through air and space, stumble-winged but fleet of foot with a flute to his lips. It’s a great spatial composition.

In terms of painterly power, however, David Aronson is outstripped by his son, Ben, whose scenes of the New York Stock Exchange floor in particular reveal one of the most energized and sophisticated brushes in the country. His high-contrast tones, boldly thick paint and slashing marks perfectly mirror the fast-moving, high-powered and high-tech world. And his large San Francisco cityscapes play up his debt to the Bay Area School: they are reserved, but luscious nonetheless.

David Aronson, on the other hand, was part of a group known as the Boston Expressionists — mostly Jewish immigrants trained at the Museum of Fine Arts — who were inspired by the success of Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine. Levine, who became one of America’s best-known social realists, passed away last year, so it’s great to see his work adjacent to the Aronson show.

Levine’s work feels like a cross between Francisco Goya and George Grosz. He sometimes satirizes his subjects as pathetically swollen and comedic, and other times as nightmarishly brutal.

While a large, gorgeous (but anxious) nude, “The Bride,” is the star of the show, most of the works are classic Levine prints, such as his brilliant “Feast of Pure Reason,” a 1970 etching that revisited his famous 1937 painting mocking the power-hungry trio of a policeman, a politician and a magnate.

The museum’s permanent collection is an important gathering of American art with a close emphasis on Maine and the historical local community in particular, and is highlighted in “Tradition and Excellence: Building an American Modernist Collection.”

The collection has an impressive roster: Gaston Lachaise, Rockwell Kent, Marsden Hartley, Will Barnet, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Walt Kuhn, John Marin, Charles Burchfield, Mark Tobey, Morris Graves and many other great American artists. The collection has an unabashed mid-century American modernist feel that, even 15 years ago, might have felt a bit musty, but today appears to have been right all along.

American art was raising something far more interesting between the world wars than an Oedipal struggle with Europe — something which came to full blossom with the international ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism in the early 1950s.

While the museums at Colby, Bowdoin and Bates, along with the Farnsworth and the Portland Museum of Art, have asserted themselves as major venues for significant American art, the Ogunquit Museum has quietly built up an historic, site-specific presence that has grown year by year in importance.

If you know the Ogunquit museum, the current slate of shows is one not to miss. If you aren’t familiar with the museum and its collections, you have been missing something both important and wonderful.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.