Walking into the main gallery of the University of Maine Museum of Art and being greeted by Joanne Freeman’s work is like sitting back after a hard day and turning on some great music; on the one hand, it’s calm and relaxed, but it also moves.

Some things transport you by changing the place you are into precisely where you want to be. This is what Freeman’s paintings do.

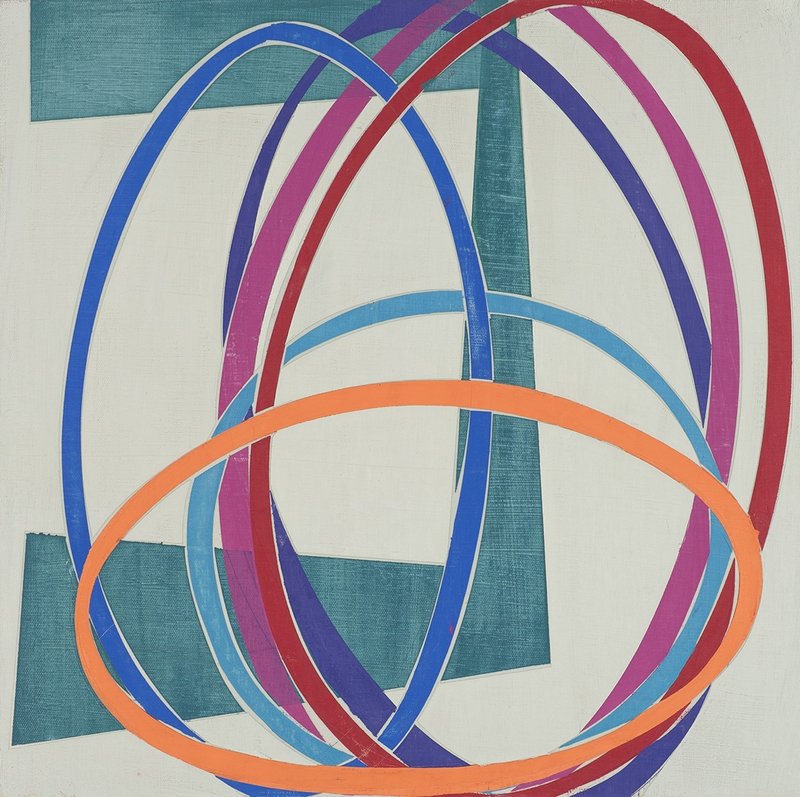

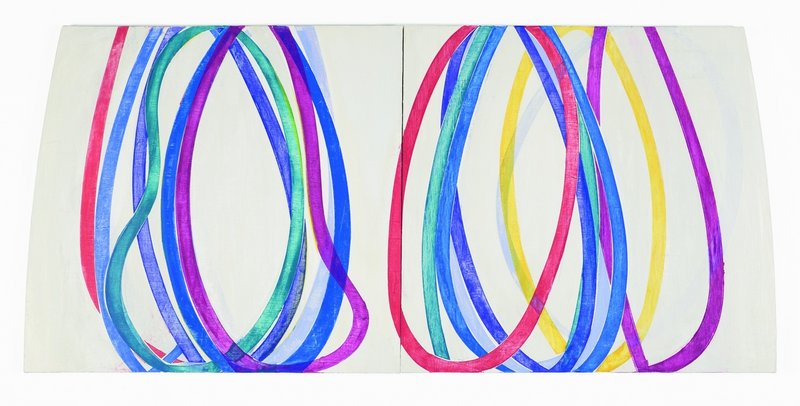

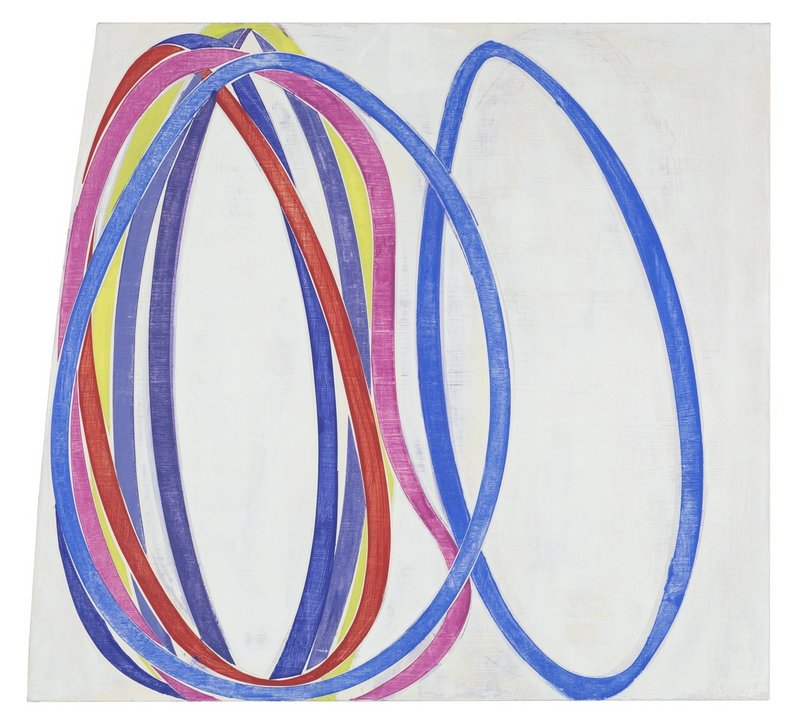

They are significantly-sized elegant white canvases with just a few loops of color: red, blue, teal, purple, yellow and so on.

Each is handsome, but as a group they exude a powerful sense of symphonic calm.

They have the rhythmic feel of Morris Louis, but most resemble Brice Marden’s looping canvases from the 1990s.

Freeman directly references musicality in her work. In fact, the strongest piece in the show is titled “Three Chords” — a direct quote of Bob Dylan.

Considering the work’s proximity to Marden, this is a little weird, since one of Marden’s best known paintings is “The Dylan Painting” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. (Marden was married to Joan Baez’s sister and was close to Dylan and other folk artists.)

By referencing Dylan, Freeman is opening the door to references and comparisons. Is she doing a Brice Marden cover? If so, why not? What musician, after all, hasn’t covered Dylan? If it’s a tribute, then it’s an elegant tribute — whatever the mix of Dylan and Marden and anything else.

Musically, the three-chord thing has meaning on its own. The basic classical music progression of sub-dominant, dominant, tonic (4,5,1 / F,G,C, etc) and rock ‘n’ roll use these same three chords for the same reason: If you play those three major chords, you hit every note in the major scale and thereby absolutely establish key.

Freeman’s use of cool and warm loops on white is like establishing a musical key — particularly since they are internally-structured abstract works. They might seem loosely improvised, but don’t fool yourself: Freeman cuts out guides for the loops and clearly works her colors and textures with a demanding appetite for perfection. She is not after fussy evenness, but the richly-textured and complex subtlety of a master painter.

While they stand strongly as a group, her weaker works prove Freeman doesn’t have a simple recipe for success. The pieces with angled edges, for example, feel much stiffer than the ones with only swooping curves. Here again, Freeman seems to be tapping into musical technicalities. After all, distortion (like on Dylan’s electric guitar) is a sine wave whose top curves are cut off by a flat ceiling; and Freeman’s curtailed forms look just like such electric signals.

THE WORK of Rachael Agundes and Shawn Downey, on the other hand, is anything but calm.

Their two-person show, “Travel in My Borrowed Lives” — a title borrowed from poet Donald Axinn — features large, psychological-expressionism-based narrative paintings that could hardly be further from Freeman’s elegant abstraction.

While Agundes and Downey now live in New York City and Boston, it’s no surprise they both hail from the West Coast. There has long been a rich movement of psychological expressionism in the Pacific Northwest led by artists such as Gaylen Hansen and the great Gregory Grenon.

While “Travel” features flawed work, it is an expansively important show very different from most anything in Maine: While our state is an art powerhouse, we don’t look enough towards the other coast.

Downey — the better painter of the pair — focuses on self-secluded survivalist characters at the edge of society where right meets left (think hippies and doomsday preppers).

Downey does not, however, make a compelling case for his subject. There is no general engagement, cutting insight or paroxysms of meaning.

Two of his best paintings include large portraits of a bearded guy in a toque smoking pot like tobacco on mountain-top rock (“Little Things”) and then a buxom young woman clad like a 19th-century prostitute drinking alone with a vague stare (“New Way of Living”). The latter work is clearly a response to Degas’ absinthe drinkers, but cast in the broken promise of the American West.

Downey’s “His Two Obsessions” comes closest to his target of creating a narrative about tracking an off-the-grid existence. It shows a hermit’s camp rendered in well-varied passages of paint. We see a book open to pictures of Bigfoot and a woman. The crypto-zoology point is clear, but the other slides between women and art. It’s a fascinating painting, but we can’t quite see it for either observation or fantasy: It’s too vague for journalism and too over-determined to be compelling as fiction.

That Agundes is hamstrung by her handling of the brush becomes apparent after seeing Emily Trenholm’s charming little show of Monhegan seascapes in the front projects gallery and then works from the permanent collection such as Dozier Bell’s warringly dark targeting map painting, Mark Wethli’s chair interior and a pair of John Marin watercolors among others.

Agundes’ dream-like association and morphing canvases are interesting, but since they rely on the creative process of painting, they succeed only when the painting is strong — and that’s limited to a pair of images of dogs in mountain-scapes (“Water Fire Fight” and the fantastic “Visiting Mount Lassen” in which the dog’s head and the mountain struggle to attain cubist status) and a jungle-ish image of a fern-surrounded morphing leopard (“She Put Chicken in her Omelet”).

Yet Agundes’ relatively weak mark-making plays to the conceptual side of her work; and next to Downey’s, we are compelled to see them as psychological narratives — and that’s a good challenge for Maine’s usual audience.

Overall, UMMA’s current slate features a bunch of very interesting paintings. It is absolutely worth a visit.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.