We’ve all heard stories about the Dust Bowl, the devastating decade-long drought of the 1930s.

But documentary filmmaker Ken Burns maintains that the Dust Bowl is, for the most part, a forgotten chapter of American history.

“For most people, the Dust Bowl can be summed up with some very superficial conventional wisdom, as bad storms and ‘The Grapes of Wrath,”‘ he says. “The story is a lot more complex than that.”

“The Dust Bowl,” Burns’ two-night, four-hour documentary, airing at 8 p.m. today and Monday on PBS, is provocative and enlightening. It will set the record straight once and for all.

The filmmaker and his team conducted poignant interviews with dozens of people, now in their 80s and 90s, who lived to tell about enduring the worst man-made ecological disaster in American history.

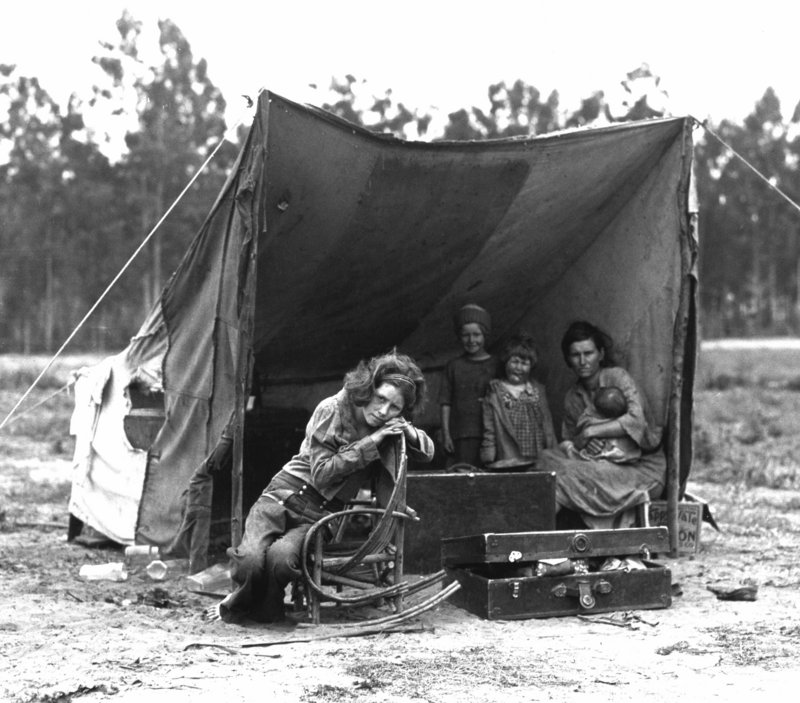

Their suffering was magnified, because it coincided with the economic blow of the Great Depression.

That said, viewers won’t fully appreciate the enormity of the Dust Bowl until footage taken by an amateur filmmaker of the day is shown. In grainy black-and-white, we see a monster dust storm, hundreds of feet high, as it approaches and envelops a small town, snuffing out the sun at noon.

Seeing is believing.

To categorize this American tragedy as a decade of “bad storms” is comparable to saying that Hurricane Sandy caused a little wind and water damage.

“This was a 10-year apocalypse filled with hundreds of storms, some of which moved more dirt in one day than it took the entire excavation of the Panama Canal to move,” Burns says. “For the people who lived through it, it was suffering overlaid on suffering.”

The Dust Bowl tragedy was the result of extreme drought conditions, but also was a man-made catastrophe.

Before the arrival of settlers in the late 19th century, the southern plains of the United States were predominantly grasslands. But at the start of the 1900s, offers of cheap land attracted farmers. And in World War I, in the midst of a relatively wet period, a lucrative new wheat market opened up.

Advances in gasoline-powered farm machinery made production fast and easier. During the 1920s, millions of acres of grassland across the plains were converted into wheat fields at an unprecedented rate.

Then, in 1930, wheat prices collapsed. In response, farmers harvested even more wheat to make up for their losses, leaving fields exposed and vulnerable to a drought, which hit in 1932.

Once the winds began picking up dust from the open fields, they grew into dust storms that became more frequent and ferocious every year. Not only were crops destroyed and cattle killed, but children developed fatal cases of “dust pneumonia.”

Thousands of Americans were forced to move to more livable locations, an exodus unlike anything the United States had ever seen.

“But this is also a story of heroic perseverance in the face of biblical plagues,” Burns says. “In the end, in the area once known as No Man’s Land, because no one thought it would ever be suitable for human habitation, three-fourths of the people actually hung on.

“That’s a testament to a gritty — no pun intended — American spirit.”

The timing of this documentary couldn’t be better.

First of all, the film comes along at a time when the oral history of the Dust Bowl is about to be lost forever. Except for one on-camera interview with a Dust Bowl survivor who was an adult in the 1930s, everyone else sharing their stories were children or teenagers at the time.

Wait much longer and there might be no one left to share a first-person account.

The film also is of interest because it addresses a very timely issue, suggesting that we’re on a path to creating another great calamity in the same area.

“One of the things that mitigated the Dust Bowl was not just the return of wetter weather and smarter soil conservation and contour farming techniques,” Burns says, “but it was also our technological ability to poke a million straws into the vast Ogallala Aquifer, which was filled with glacial melt.

“But this is not a sustainable water supply. It’s not a reservoir that refills up with snow melt and rain water. This is a case of us mining for water. The Pollyannas among us say there is 50 years of water left. The Cassandras among us say there are only 20 years left. Whoever is right, we’re going to run out.

“And then what do we do? Is there any contingency for what happens when the Ogallala runs dry? Are we prepared to permit an American Sahara Desert to sprout up in the Southern Plains?”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.