BRUNSWICK – For years, Katherine Bradford has invited curators and museum directors to her summer home on Mere Point Road in hopes of landing an exhibition, piquing curiosity or perhaps placing one of her paintings in a collection.

Mind you, her oil paintings are already in museums in Maine. The Portland Museum of Art just added her painting “Flying Women” to its permanent collection; it’s hanging in the Great Hall.

And Bradford has shown her work around Maine, and around the country, for many years. She’s won grants and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation and others.

So she is hardly a struggling artist desperate for attention. Indeed, among institutions that collect her work are the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum.

But she always coveted a show at Bowdoin College, which is just a few miles from her summer home.

“Every summer, I would invite the curator to my studio. Every summer, I would give the curator lunch and laugh at their jokes,” she said. “And then I met Joachim, and he laughed at my jokes.”

Joachim Homann is Bowdoin’s sharp young curator. He loved what he saw of Bradford’s work, particularly her recent water-themed paintings of ocean liners and swimmers, and quickly agreed to a summer show. Fittingly, it is called “August.”

It is a perfect complement – in temperament, style and attitude – to the summery feel of the Maurice Prendergast show that Bowdoin is also hosting this summer.

Whereas Prendergast takes an early-20th century perspective on the beach-going culture, Bradford considers similar subjects with the looser, less literal approach of a 21st-century painter.

Both make similar use of color and form, but she is less beholden to tradition and more apt to infuse her work with the risk of abstraction.

Her beach scenes merely suggest human form. Her swimmers dive into infinity. Her Titanic sails on an orange sea, iceberg beckoning.

As she considers her rudimentary “Night Divers,” she anticipates the criticism. “I think some people would look at this painting and wonder if I knew what I was doing. It’s not a finished kind of skilled painting,” she said.

But she was not after elegance. She wanted to suggest what it feels like to dive off a boat or dock in the darkness of night into black water. It’s about mood and atmosphere, not technical excellence.

“Sunbathers” shows two people sunning themselves on a beach. One is orange; the other a brownish-green, almost avocado-colored. Homann asked why she chose those colors.

“I wanted diversity,” she said with a shrug. They both laughed.

“Joachim can feel the sense of fun and play in my work,” Bradford said, relieved.

The painter and curator hit it off instantly. She appreciated his open mind, and he found her work hilarious and comical, but also catastrophic. There’s nothing funny about the Titanic, he said.

This is a very small show – fewer than a dozen paintings. It is hung in the museum’s Zuckert Seminar Room, a boxy gallery with high ceilings that well accommodates Bradford’s large-scale canvases.

There are many small paintings as well. Homann insisted on both, because the range of work speaks to her dexterity as an artist.

“The large canvases with these bold ships are really overwhelming. But then these tiny things are so witty and beautifully thought out,” he said.

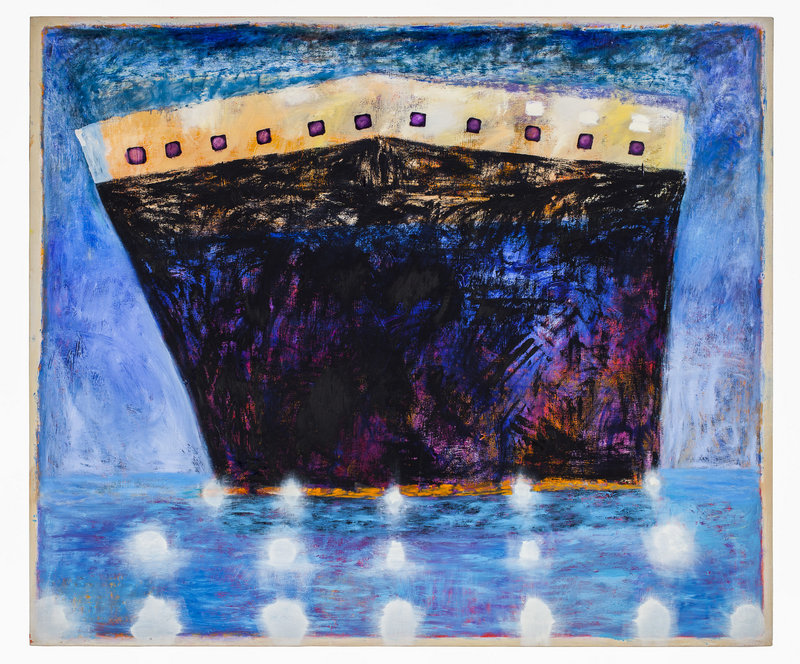

The talker of the show is a nearly 7-foot-wide canvas called “Ship in Blue Harbor.”

It hangs on the gallery’s far wall, facing into the main part of the museum so it is visible from the Prendergast galleries. It serves as a magnet that draws people in.

“Harbor” may be the most painterly piece of the bunch, showing a large ocean liner from the perspective of just below the bow. The ship sits high on the water, towering above like a beast. In the foreground, in front of the vessel, is a series of what appear to be small white lights arranged in a grid, surfacing from below the blue.

Whatever they are, they are. I read them as phosphorescence, which night swimmers often encounter in the ocean. Regardless, the white lights set the ocean aglow and give Bradford’s painting an otherworldly feel. It is a beautiful painting, rich in texture and deep in tone. It would look great in any museum.

Bradford has long been associated with the Maine art scene, and stands today as one of the state’s most successful and revered contemporary painters. Some have argued that her creative lineage descends from the great Maine modernists Marsden Hartley and John Marin.

Bradford spends summers in Brunswick. The rest of the year she is in New York – Brooklyn, to be precise. This summer, she is busy preparing for a gallery show in New York in September.

And while she is not basking, she certainly is pleased with the attention the Bowdoin museum is giving her.

At the opening a few weeks ago, she was particularly happy that two of her four young grandchildren were able to attend. They had fun seeing their grandmother in her element, and perhaps wondered if the roles were reversed. Maybe it was they who were grown up, and it was Bradford acting with childlike glee.

As she reflected on her life and career, the painter allowed that her dreams are coming true. Some of them, anyway.

What else does she dream?

“I would like to be the kind of artist who can do excellent work and is still well-regarded by her children and friends,” she said. “I don’t want to be a monster artist.”

Unless monsters are given to humor, she can count that as a dream come true as well.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.