An art market bubble burst in the late 1980s. An age of intoxicating indulgence was superseded by a new focus on craftsmanship, effort, skill and material mastery. Painters began using a wider range of materials, such as encaustic, and reinvigorated processes like glazing with oil paints. A high sense of finish came back into vogue, and there was a broad move away from chance toward clarity of intention.

The American Craft Movement’s steady expansion since the 1950s helped make espousing craftsmanship feel inevitable. Craft mediums surged even during the downturn, so painters, photographers and sculptors decided to take lessons from craft. They learned that the fundamental effect of fine craft is respect for the audience.

While craft demands great effort and informed technique as the vehicle of content, it also insists the artist must be humbly observant and see the beauty inherent in his material as well as his subject.

Many current American art concepts came from Eastern ideas about craft, notably wabi-sabi — the Japanese aesthetic philosophy. Wabi-sabi rides the asymmetrical, imperfect, humble and organic. While it stems from Buddhist notions of impermanence, it fits (superficially) with American ideas about loose and gestural art driven by spirit and self-expression.

One key element of wabi-sabi is the aesthetic of natural processes. Ceramics and heavily worked paintings come to mind, but this is also a key element of American photography. Think of Walker Evans’ weather-worn Midwest or the decaying grit of urban photography — or even Maine landscapes featuring rocks carved and polished by relentless weather and sea.

One of photography’s great powers is the ability to lead us to see the otherwise overlooked. It can show us abstractions in mundane or natural objects, or offer miniscule bits of reality for contemplation.

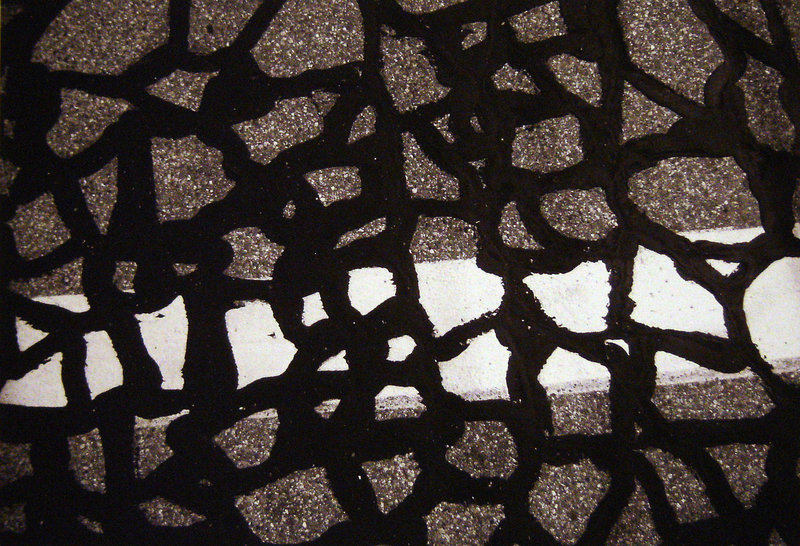

Katarina Weslien sees the overlooked. Her “Lines Portland” is an exhibition of images of road repair lines in Portland. It’s a brilliant idea for a show at City Hall, because it illustrates the effects of the climate on our roads and the effort of public services to maintain them. Where others see ugly erosion, Weslien sees bold abstractions.

All of the repairs pictured in the show feature the ubiquitous black-rubber sealant streaking Portland’s streets. Weslien’s photographs look straight down on the repairs, so the sealant looks like thick black brushstrokes.

This is both where and why “Lines Portland” succeeds. The calligraphic marks are made by hand-like brushstrokes with what looks and acts like paint. They are human gestures following the organic lines of natural processes, so they follow logic common to Abstract Expressionist painters such as Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Willem DeKooning and many others.

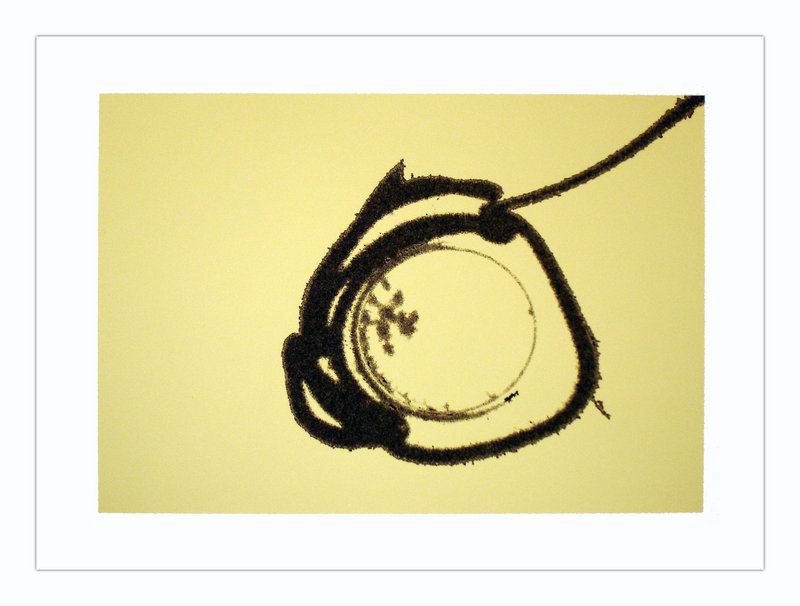

In addition to the photos, Weslien presents prints she created by burning out everything in the photos except for the thick tar lines snaking over solid butter-yellow backgrounds. Without the photos to explain them, they would make for some strong abstract images, since the painterly gestures are bold and (somehow) logically structural.

The third set of works in the show is very interesting, though deeply flawed. Weslien took three of the images also shown as photos and worked in features from maps of India. These are conceptually compelling, but the superimposing of images was poorly handled. (Also, because Weslien is an accomplished printmaker, I was disappointed with the low print quality of all the works in the show.)

Still, these reveal a fantastical side of Weslien’s imagination: you get the idea she sees exotic (even Seussian) worlds when looking at the cracks in the road. They also reveal humanity’s need to map its culture around natural forms and, conversely, they remind us that the cracks in the road are the result of nature’s unstoppably inserting itself onto humanity’s cultural forms. (Ironic or inevitable?)

Weslien also presents a large map of many sets of Portland’s “lines” including zoning, sewer and storm, steam and drainage, fire and police, and bike, bus and ferry lines. While “Lines Portland” fails to make the conceptual jump between the maps and the painterly road repairs, the maps are affably educational and set a thoughtful stage for the more artistic work.

Weslien seems to have a broad cultural take full of workers, community, function, economics, cultural aesthetics, seasonal erosion and a heavy dose of wabi-sabi. While she appears to have tapped into some sophisticated ideas about seismic shifts in our aesthetic culture, “Lines Portland” is easy to enjoy, and delivers some highly portable messaging.

If Weslien’s main goal was to help us see what the city of Portland does for our communities, then “Lines Portland” is extremely successful. Presented by Art at Work (a partnership between the city of Portland and nonprofit Terra Moto), it is thought-provoking and fun — and it gives the average citizen a good reason to check out Portland’s handsome City Hall.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at: dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.