Anyone reading this article is apt to know more about the Maine Museum of Photographic Arts than I do. I believe the MMPA to have a virtual existence — an institution that exists in some intangible fashion rather than in physical fact. In short, a museum without walls. But that doesn’t preclude it from borrowing a good wall when it can find one.

Take the Ogunquit Museum of American Art’s idiosyncratic walls, for example. A hark back to the days of split-level architecture, the walls’ up-down bounce makes them a genial host for photography with a similar beat.

That confluence of energies is absorbed by “Light, Motion, Sound 2012” and tossed back at the viewer. The exhibition, with more photographic pulse than I’ve felt in a long time, is a collaboration between MMPA and the very tangible Ogunquit institution. The whiz of its images superintended from out the window by Ogunquit’s rough chunk of the coast is thrilling.

The show is intended to explore the way photographic images are made in Maine in 2012, and offers work to that end. I don’t have names for all of the processes or approaches that appear in the show, but the event makes it clear that while many are still emergent, they can have intensity and substance. Current technologies and attitudes are not playgrounds for rookies.

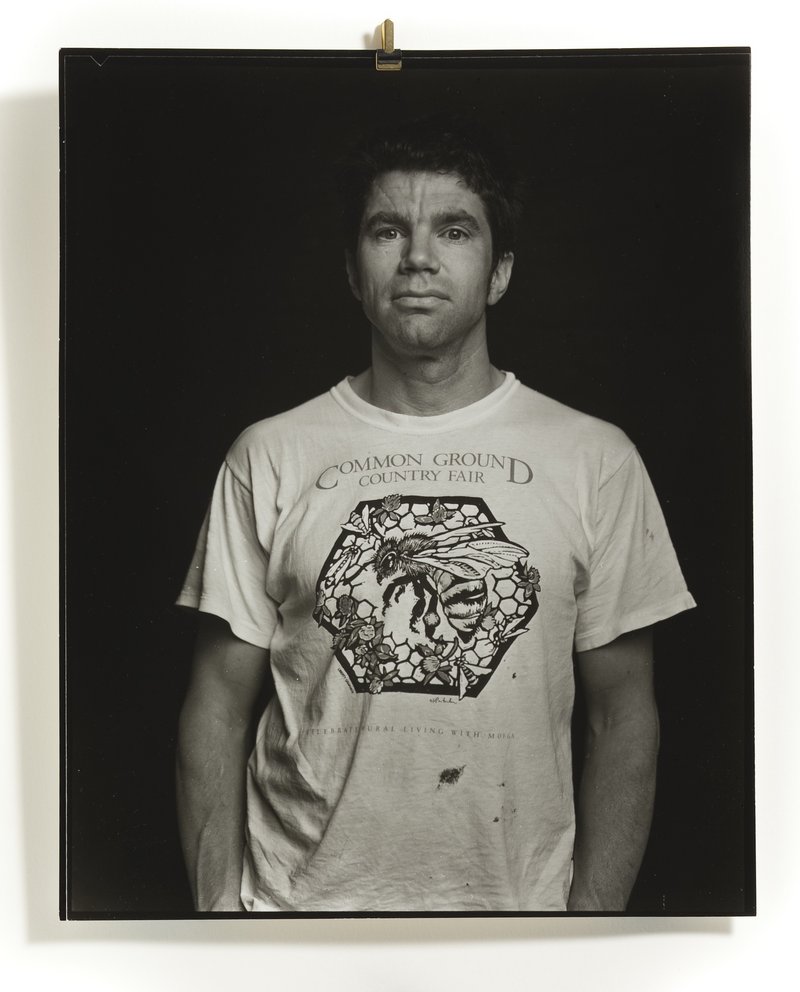

Luc Demers, in 15 silver gelatin portraits, is the most traditional of the group. In making his images, he asked each sitter to select a moment in the past and hold a memory of it in mind. The camera’s exposures are of people reliving that moment, and Demer’s dark prints acknowledge it. There is an emotional transference from the exposure time to the film, and while you can’t penetrate it, you know it’s taking place.

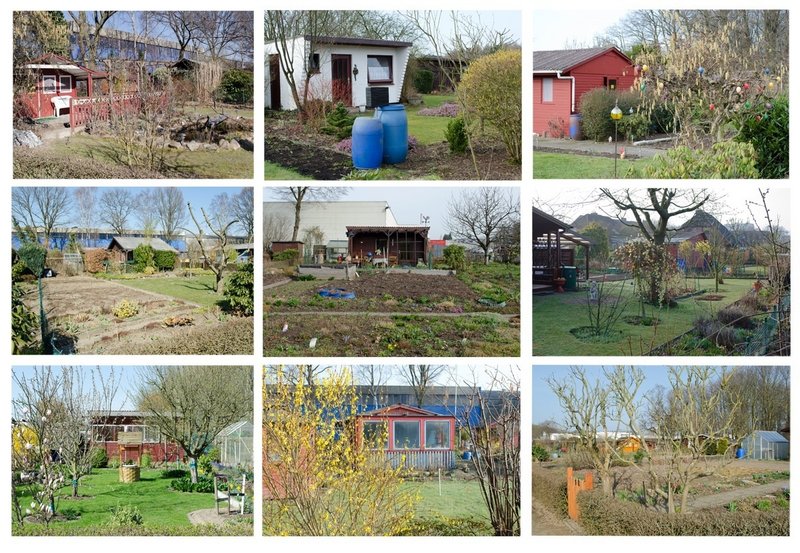

Elke Morris also offers traditional images, but in inkjet color. They are of small tracts of land (called “Schrebergarten”) set aside a century ago in a community in Germany for the physical exercise of urban children. It was a progressive effort, but time, events and attitudes modified that use; the tracts became gardens cultivated by adults, and finally, they were reduced to space for recreational purposes. Morris is matter-of-fact in her presentation; the land and the structures on it speak for themselves, and their story is of nostalgia and soft melancholy.

Jonathan Laurence’s “Images from Shapes v2.0” consists of tiny tape-bound color images suspended from high in the chamber to about eye level. There are 365 of them, made one a day for a year starting in April 2011. Floating there in space, they speak more of the passage of time than of formal interest. Perhaps that’s the whole idea.

Noah Krell’s two single-channel HD video works, “42 Years of Miscommunication and Joy” and “To Move a Body,” are stated to be in the space between photography, film and performance and offered for a sense of immediacy and palpable physicality greater than the mediated images themselves.

“42 Years” is too complex to describe here. “To Move a Body” is a video of a young woman giving a tall young man a piggyback along a big city street, and it meets the photographer’s prescription. There is a sense of physicality that exceeds that in the sequence itself. These efforts may say more about the direction of photography than any other in the show.

I note Mark Ketzler’s graphic color digitals “East River” and “Bangkok.” Altered portraits of formidable buildings, they are intended to emphasize the perceived intent of the respective architects. Whether Mr. Ketzler’s perceptions are accurate I cannot say, but I can say that his images are big, bold and handsome. I also note Amy Stacey Curtis’ dual installations of a road in Bowdoinham made at different video footage speeds. It’s a fast and almost furious excursion.

There is much in this show closer to the edge than this article implies, including an in-the-flesh, cosmetically altered 1988 SAAB 900 by Dan Dowd. It’s accompanied by a sales brochure altered by Mr. Dowd to suit his alterations of the vehicle. Called, jointly, Projekt 900, it is taste and cleverness raised to a high pitch. The actual car and the brochure herald the imaginary rebirth of a no-longer-produced brand of motor vehicles, modifiable to suit the whims of customers. Don’t miss either. They constitute a virtual rebirth for use in a virtual museum.

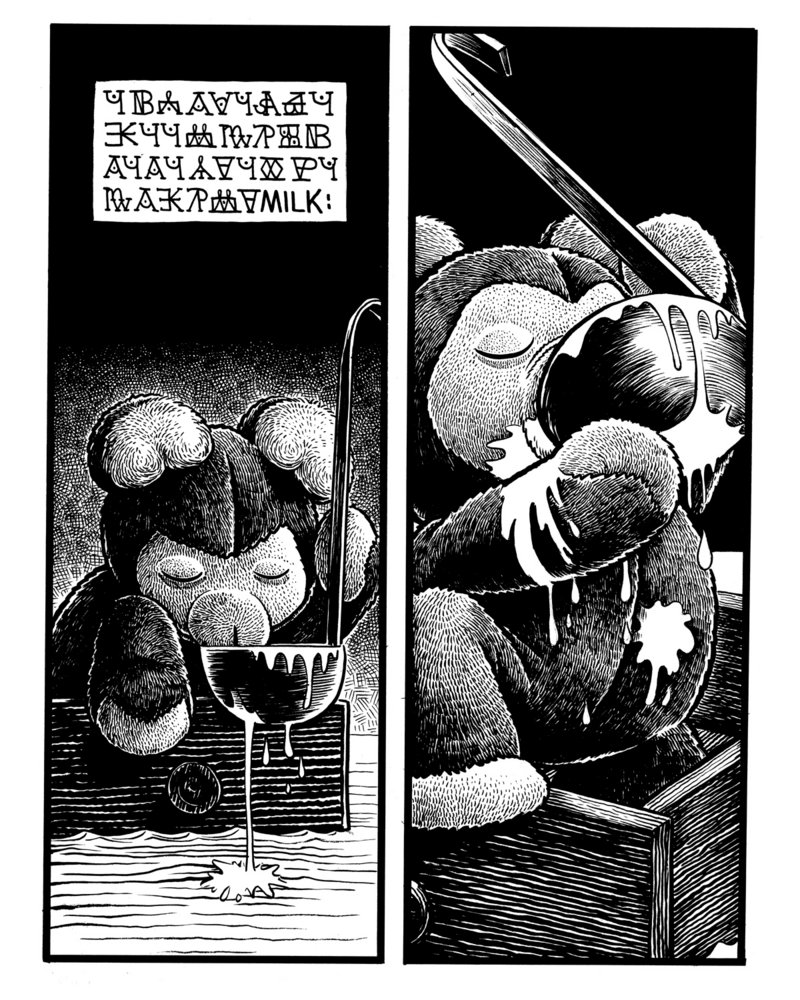

IT IS A PLEASURE to direct you to “Reading, Writing and Defining: USM Book Arts at Stone House Faculty Exhibition” at the Atrium Art Gallery, USM Lewiston-Auburn College. It fuses books, printing, typography, bookbinding, graphic design and artist’s books into a single event that is wonderful in its subtlety and reticence.

It is so subtle that you wish that you could close the gallery doors and be alone with it. Fusions between art and crafts — when they occur — are best appreciated in private. And like all fusions, some struggle to fit the definition of the event. The key term here is “Book Arts” and not “Art of the Book.” Art in this show is not the servant of the book. It is a component in a new entity and loses its traditional identity.

The show’s 24 participants have served as faculty at USM Book Arts at Stone House Program, an annual weeklong institute that gathers book artists with others interested in the artists’ books as a form of expression. In artists’ books, there are no holds barred. Painting, printing, drawing and photography merge into accordions, popups, scrolls, sheets boxed and unboxed, and more. There are even books that look like books.

I note, among the many, Colleen Kinsella’s “Cityscape,” an ink and collage irregular popup that converts landscape into an urban place, aloof and a little dangerous. Nancy Leavitt’s “A Ship of Thoughts (how books carry the human soul)” is beautifully buoyant in the precision of its accordion structure and corset and the geometric elegance of its appointments.

Mary Howe’s “Show Tonight” of bookcloth, pastepaper and board establishes a circus in a box complete with clowns, wagons and the like. It is a tour de force of playfulness and technical skill.

Erin Sweeney’s “Story Tellers” — stuffed, tubular figures with letter-pressed forms holding blank-paged books — move closer to distant realms that find their way into artists’ books.

I further note the beautifully toned photograms in Anne-Claude Cotty’s “The Silent World Is Our Only Homeland,” and Karen Adrienne’s text-covered objects in her “Equity.”

These are important exhibitions. One loosens the bounds on photography and very certainly reveals one or more paths the future will take; the other loosens the boundary of what might define a book. Both remind us that photography and books are subject to continuous redefinition.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 47 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.