Writing about the craft arts is a refreshment. It is a moment away from an account about paintings — often a search for quality among the tedious — and from photography.

The latter once came as a tonic to us. Less pretentious in its pure form than painting, it offered clarity, insight and a sense of the moment. It has not yet become a full vassal of the computer, but its submission to the indulgences that computers offer have softened its edges and the attraction of writing about it.

The crafts are not exemplars of absolute purity. Still, there are craft artists schooled in tradition and so graced with a sense of mission that their work brightens the world. They are the pure and the few in number. The many roam the fields of the fine arts. They borrow from the painters, and they convert craft objects into bits of sculpture.

This is not because the craft genius is expiring; it isn’t. It is because of a perceived need for certification. The closer a teapot gets to Brancusi, the more significant; maybe so, but probably not. Better to allow the ingenuity and wild liberty available in the materials and psyches of the makers to govern the product.

These not-new thoughts are brought on by “The Inspired Hand V” at the University of Southern Maine, Lewiston-Auburn College, and a cracking good show it is. It elevates the spirit and confirms my prejudices. An assembly of long-acknowledged and new-to-me craft artists, it’s a treasury of beautiful objects — some classic; some dancing on the edge of funk.

For funk, take a look at Edward Mackenzie’s “Piano Parts Necklace.” Except in remarkable circumstances, it would be more for display than adornment.

Mackenzie is a genius at improvising. He rarely alters his material. Rather, he accepts it physically as found, then rearranges it to create new personas. To an artist like Mackenzie, a piano is a gold mine; an aggregation of fascinating, beautifully made and unexplainable pieces. His use of them balances between whacky and ingenious.

Perhaps the research incorporated into Willy Reddick’s brooches disqualifies them from funk, but they are fascinating. Immaculately painted images of eyes are encased in small but formidably riveted brass and tin frames. The contrast between the staunchness of the frames and the suave elegance of the eye is the thing. Incidentally, the eyes are accurate; they can be borrowed from Princess Diana, Martin Luther King Jr., Amelia Earhart or the artist’s cat.

Kenneth Kohl’s mirrors, although shrewdly organized, suggest cavalier arrangements of tidbits found in a cabinet shop. They are charming.

For tighter work, there are the grand masters Lucy Breslin, J. Fred Woell, Lisa Hunter, Jacques Vesery, Paul Heroux, Morris David Dorenfeld, Christian Becksvoort and Katharine Cobey. Still, there would be plenty to see without them. It’s a 35-person, beautifully juried show, with Susan Perrine’s “Contraposto” hut or Meryl Ruth’s “Her Majes-Tea” teapot as likely to haul you in as anything else in it.

This, as the title indicates, is the fifth in a series of biennials held jointly with the Maine Crafts Association. That partnership is a great benefit to the encouragement of the craft arts in Maine.

______________________________

TWO SHOWS at the Bates College Museum of Art add strength to my conviction that small museums often best bear the weight of demanding exhibitions — shows that deeply engage the intellect or cross areas that annoy or confound the public. Each of the events at Bates are, for Maine, uncommon.

One, a portfolio of lithographs by James Ensor, and the other, paintings and other work by the artist Xiaoze Xie, are within the historic range of Bowdoin exhibitions, but that is pretty much it. Each Bates show, splendid in its fashion, opens areas that engage the audience and require its cooperation.

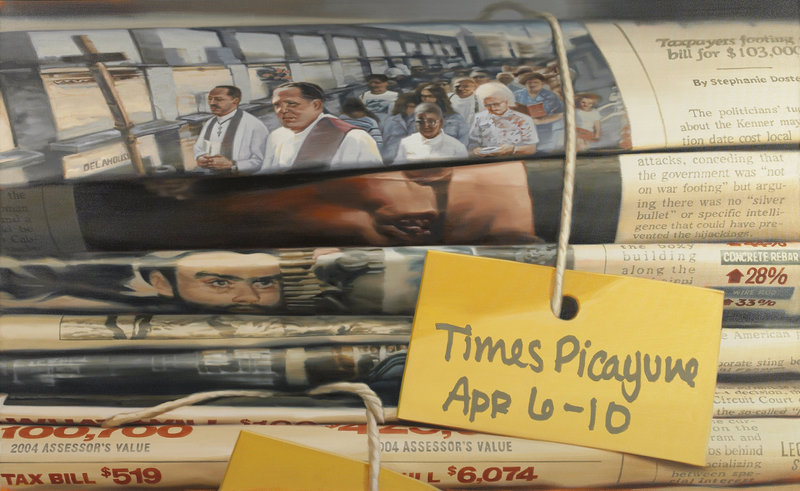

First, Xie’s show, “Amplified Moments 1993-2008.” Here, Xie is more painter than photographer or maker of videos. The scale of his work is large, and the effect is voluptuous.

The subjects, largely books and newspapers, are presented in architectural or archaeological order. In Xie’s world, they confront viewers with unexpected dignity and with reticence about their contents.

Neatly stacked newspapers are forbidding; to excise an edition from a stack is to disturb the labor of others. And the alteration is beyond remedy. The logic of the initial creases, the later foldings and the construction of stacks by daily ministration, are all lost. An edition returned to the pile does not restore the pile; it creates a new pile and a history disappears. And if the sheets are old, each touching is an assault.

Old newspapers have secrets and can guard them well. They may exist for themselves, for their elegance when respectfully piled, and perhaps for no more than their ability to be folded into thick arcs and defy the archivist. Perhaps they exist simply because they exist; many things do. All of this I extract from Xie.

Books are another matter. They are not cavalier about their hides. They slip into book covers, dust jackets, slipcases and archival boxes where they can be dusted, admitted to eternal twilight and delivered of all evil. They appear to be standing in serried ranks, but they’re not. Something else is doing the standing for them. This too is a lesson from this artist.

Xie’s paintings are gorgeous, and represent matters infinitely more consequential than the physical display of things printed. I urge them on you, and suggest you note the sophistications of their installation.

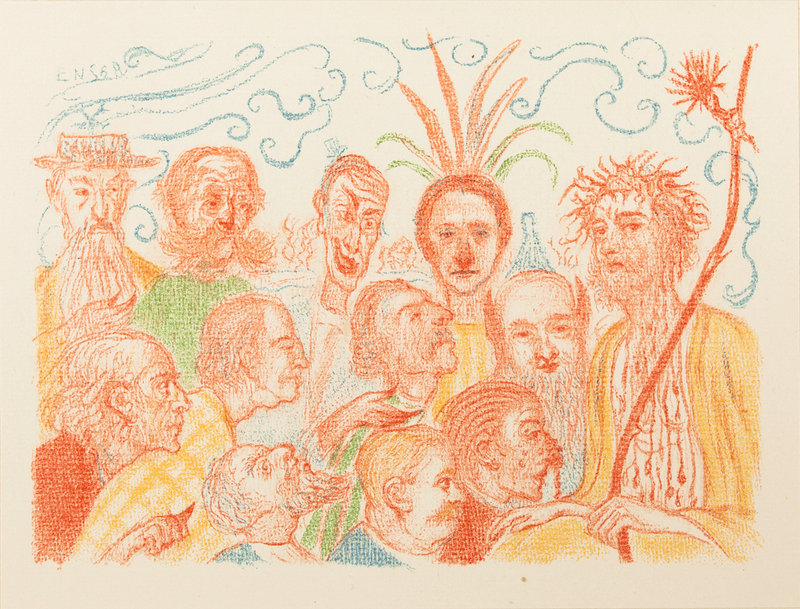

The Ensor show, “Scenes de la Vie du Christ,” is smaller and almost evanescent. It consists of a few grand — and famous — etchings and a suite of 32 lithographs on paper that depict scenes from the life of Christ. The small scale of the work in the suite and its almost fugitive printing give Ensor’s often bizarre figures a transparency that challenges their peculiar severity.

Ensor was a master of the grotesque. He drew from the restless world of dreams. To present the bizarre in angelic colors is an exercise that is both addled and enchanting. It is a privilege to see these wonderful images.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 46 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Correction: A photo caption with this story was revised at 9:45 a.m., Feb. 13, 2012, to correctly identify the teapot piece. It is “Her Majes-Tea,” by Meryl Ruth.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.