We are carbon-based life forms. All life on Earth is carbon-based. Carbon is small, light and abundant, and it happens to have a practical atomic structure for making complex molecules.

But where does that carbon come from?

The carbon atoms in your body come from long-dead exploded stars — probably even from thousands of different stars.

Every bit of oxygen you breathe and everything you touch was made possible by star death.

There is a section of “Starstruck: The Fine Art of Astrophotography” at Bates College Museum of Art in Lewiston that is all about “star death” — the step-by-step process by which incomparably powerful processes of destruction and creation give birth to each other.

If you don’t know — or care — what’s going on with the cosmos, “Starstruck” is still extraordinarily beautiful. Whether you go for photography, art, science or spirituality, “Starstruck” is one of the most moving and intriguing exhibitions to alight here in, well eons.

If you don’t know about astrophysics, you have all the more reason to go. All you have to do is look.

(If the subject intrigues you, get the excellent catalog; I couldn’t put it down until I had read it cover to cover.)

I also had the great fortune of visiting “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” at Space Gallery in Portland before visiting “Starstruck.” If you can visit them in that order — do it.

Curated by Liz Sheehan (formerly of Bates), the Space show is about the visual translation of data into conventions guided by our aesthetic sensibilities.

Nathalie Miebach, for example, translates meteorological and oceanic information into two giant, complex molecule-like buoy forms that illustrate data sets. They are simple substitution ciphers, but they reveal how intricately vast these systems are.

I most enjoyed the works of Bartow+Metzgar’s “non-human drawings” in part for their wide-eyed naivete — as though they were the first people to let nature do the drawing. The drawings resulting from attaching drawing platforms to tree limbs for a particular amount of time are particularly interesting as a group, because together, they start to feel legible.

They wander onto the turf of seismographs and sundials, but in a way, that reveals the human instinct for conjectural knowledge — which is more akin to tracking or detective work than scientific method.

Bartow+Metzgar are trying to create languages to decipher, but they are starting with the indexes rather than any natural phenomena to explain.

One striking similarity is how Bartow+Metzgar’s labels at Space resemble Hans-Christian Schink’s exhibition labels at Bates: They are lists with data points relating to grids of works on paper.

Schink’s extraordinary photographs are created by pointing a camera at the sun to expose film for one hour from various points around the globe. Alone, any image looks like a darkroom accident with the thick black line near its center. But together, they reveal what is going on: The black line is the path of the sun (weirdly — but predictably — the hyper exposure goes black).

The direction of the line depends on several variables, including where in the world you are; and Schink shows the landscape for context.

Deep in the spiritual and technological wonders of “Starstruck,” I was momentarily horror-struck when I first saw the black nuclear-sun streak over Japan. But I doubt that Schink, from Germany, ever felt what I did right then.

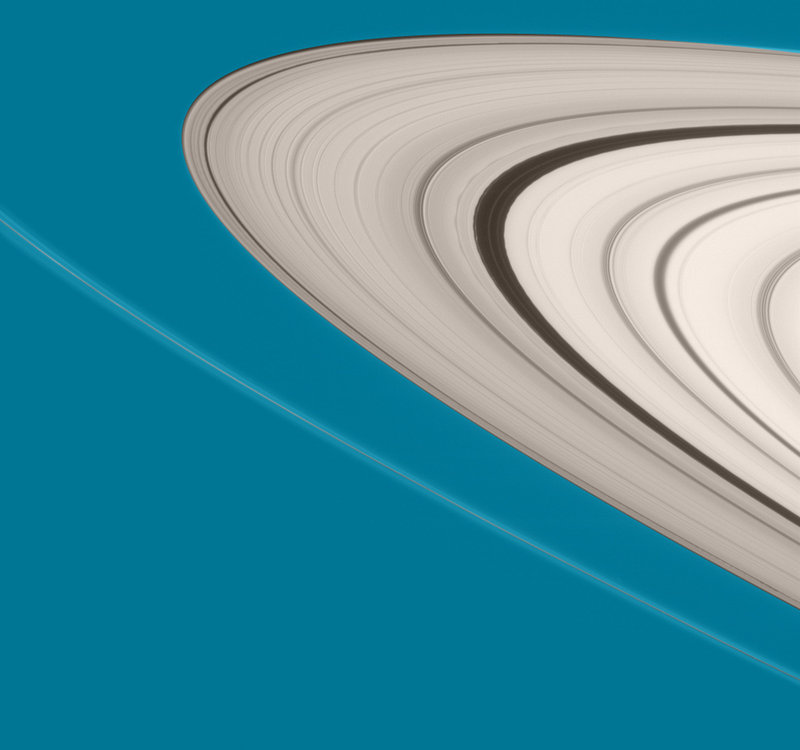

In fact, the works are from around the world, and it’s a great combination of invited artists and juried inclusions. Jury-found Frenchman Jean-Paul Roux’s “Blue Moon Eclipse,” for example, is the most artistically beautiful photo of the moon I have ever seen.

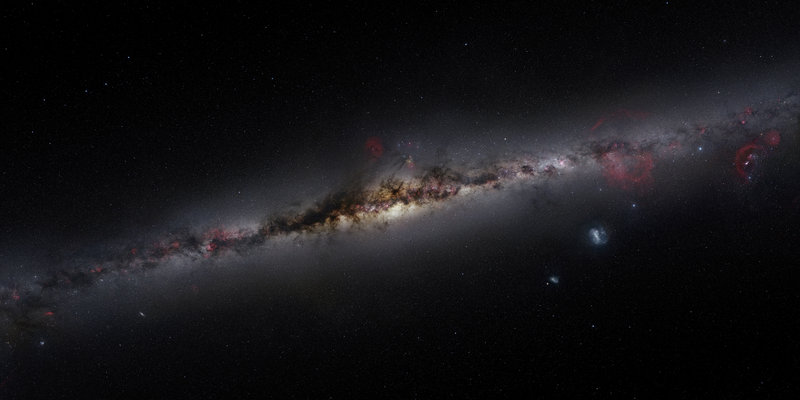

Most of the images of “Starstruck” are the colorful star and dusty cosmic cloud photos we often see reproduced. But they are magnificent — and more so for being together.

Together, their meanings gather momentum; they create context and shed light on each other. Any is worth hours of study, but just running your eyes over the group for a matter of minutes might bring you to conclusions beyond what you thought you could imagine.

Too often, we think of photography as a flawed analog limited by the human eye. But photography can show us things we can’t see. Combined with computers, multiple shots from smaller lenses can see things huge telescopes can’t. This idea, illustrated beautifully by the web-originated images of Damian Peach, was largely new to me.

With light, white is the result of all colors. By using filters, we are able to see differently colored things within the white galactic dust — and programs like Photoshop can create visual distinctions between, say, the similar reds of sulphur and hydrogen ions.

Astrophotographers now commonly use the “Hubble palette” — a set of conventions for conveying certain invisible wavelengths as colors. It’s a reminder that color is not a quality of objects but the conventional translation of wavelength data by our brains.

Indeed, photography can show us the invisible.

Photography’s conventions also make it understandable. For example, when the diffraction spikes of some bright spots don’t line up with others, we know the image was “stitched” (compiled from multiple photos) such as in Robert Gendler’s “Great Nebula in Orion.”

In many ways, the star of the show is Nick Risinger’s 10-foot-wide “Photopic Sky Survey.” It comprises 37,440 exposures revealing a 360-degree view of the night sky in a 5,000-megapixel image. It’s a mind-boggling scientific document that began as a work of conceptual art.

“Starstruck” is just as likely to change your understanding of photography and art as change your understanding of the universe. And it will change your understanding of the universe.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.