The Bates College Museum of Art is in many ways the most favored of our principal museums. Because of its size — bright and tidy — and a supportive administration, it is able to pursue interests that are unusual. They tend to be eclectic, provocative and beyond what is offered for general stimulation. In short, it’s an academic museum given to suggesting horizons rather than repeating oft-told tales. In some ways, small can be better.

These are the closing days of “Tale Spinning,” an event at Bates that I should have reported upon months ago. It embodies what I have said about things eclectic and provocative.

An introduction to the role that the bizarre plays in art, it urges the eminence of James Ensor (1860-1949) as relevant to our time, at least to me. The museum offers it as an affirmation of the tradition of telling stories worth telling — stories that amuse, confound, that have moral content, that should remain in our culture.

I see the current show in those terms. It does so with things grotesque, bizarre and weird. Often fascinating, those qualities are part of our story, and are only perverse if we say they are. Ensor famously drew upon the bizarre in human conduct to rail against depravity and our other shortcomings.

Other artists, as this show tells us, draw from the same tradition. Their stories are not popular, and that gives “Tale Spinning” its poignancy. It’s an opportunity to see the work of accomplished artists that employ difficult forms to tell peculiar stories — stories we only partially comprehend and with many meanings.

Six artists comprise the show. Their work is too varied to allow a comprehensive definition, but that of Brad Kahlhamer and Enrique Chagoya fit most easily into my conception of the stream of the bizarre.

Chagoya draws on religious icons, Goya, Aztec gods and popular cartoons to invent stories to be remembered. Kahlhamer’s images are more composite, but his sources are the American West, its people and its things, both actual or imagined, joined to one another by fantasy.

Telling stories about this show is just that — stories. More so than most recent shows, it requires a commitment to seek understanding, rather than just to be appreciated. Even that commitment won’t open every one of its doors.

I was enchanted by the show.

“FORMAL EVIDENCE” at Zero Station introduces itself as work by three artists utilizing formal, historical and experimental methods related to photography. It’s an apt description. In one way or another, the show has components that draw upon traditional, pre-digital image making. It speaks of commitment to the values of photographic tradition and non-electronic skills. I note the substantiality of the event by pointing out that it is produced by a guest curator, David Segre, an applaudable effort by Zero Station.

There are three participants: Cole Caswell, Thomas Birtwistle and Bryan Graf. Caswell’s principal images are of the Meadowlands, the gigantic toxic dump that has served the New York City area. They were obtained through the ancient wet plate collodion process, a technique of heroes. It requires hauling a darkroom around from site to site and other efforts that are indescribable.

Caswell prints the large negatives so obtained on lightly treated common newsprint. The resulting huge images, in their physical coarseness, speak eloquently of the subject matter. The grittiness and imperfection of their sheets become adjuncts of the horror of the dump.

On a different subject and a more experimental level, two large black-and-white images garnered by exposing film treated with chemicals in a damp cellar have celestial suggestions. The bizarre markings, whatever their cause, suggest things that are not of our world.

Birtwistle offers five formal portraits of jarred vegetables and other consumables (can you eat dried clover?). In their self-assurance and perfection of their arrangement and elegant state of preservation, they achieve iconic status. They seek veneration, and meet you head-on in homely splendor.

Graf’s work is a presentation in the workings of an aesthetic evolution. It starts with a Polaroid of a simple view from a window or perhaps of a clutch of wisteria or a borrowed snapshot of a lake. From there, in reproduced form, it makes its way onto a sheet of sunbleached paper, which, in turn, inspires a photo created on a black-and-white negative.

My details on the process may not be precise, but the fact of the transition is the thing. The existence of a path is where the fascination lies.

This is a fresh, unusual show. It tells us something about where photography was, and suggests realms to which it might go.

I DON’T REVIEW SHOWS in restaurants. For one thing, I don’t like to interrupt people while they’re eating and having a good time. I draw sketches while making notes, and that interlude interferes with the rhythm of patrons eating spaghetti.

I depart from this iron-clad position to acknowledge the seriousness of purpose of the Salt Exchange’s art program, and because I found the freshness and enthusiasm in the paintings by Don Peterson arresting.

They are the work of someone who loves to paint, and I take note of it while that impulse is still dynamic.

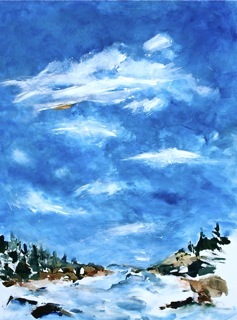

Peterson presents marine landscapes that range in accomplishment, but I found “Toward Todd Bay” and “Mood Indigo #8” handsome. The artist has the gift of animation; the show implies that his images will forever be on the move.

Philip Isaacson of Lewiston has been writing about the arts for the Maine Sunday Telegram for 46 years. He can be contacted at:

pmisaacson@isaacsonraymond.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.