I once gave a talk about Lois Dodd when she was sitting 10 feet from me. Intimidated, I hesitated, then began with her quote, “I am cheap with the paint.”

She nodded.

That only reinforced my image of Dodd as the archetypical Maine painter. Sure, she is from away, but she has had a place in Maine since 1951.

She’s actually more spare and efficient than cheap. Dodd’s Shaker-flavored New England simplicity is a quality of early Modernism we see in her precedents such as Edward Hopper or Marsden Hartley.

Dodd’s work is observational: What she sees is what we get. She paints the world around her — her house, the nearby woods, the garden, the local landscape — but also her geometrically urban world when she plays Persephone in New York City.

Dodd is known as a “painter’s painter” but only because the public hasn’t yet fully come to know her work while painters such as Will Barnet, Alex Katz and Philip Pearlstein have long been fans.

“Catching the Light” at the Portland Museum of Art makes a clear case that Dodd is a painter for everyone, from the professorial elite to the average person on the street (and, yes, painters too).

The best way to explain Dodd’s work is Matisse’s famous (and controversial) “armchair” quote: “What I dream of is an art of balance, purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter — a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

“Catching the Light” is a great-looking show. It’s easy to see and enjoy.

I adore “Woods with Falling Tree” (1977). It’s a large, vertical landscape of thick Maine woods. In Neil Welliver’s hands, the forest would be impassably thick and dense, like his paint. But Dodd’s path is visual, not physical, so her eye travels far and wide through the scene, following trunks, branches and the light trickling down from the sky.

Dodd’s forest exudes life; it breathes. Instead of welling up weightily from the bottom, Dodd takes a trick from Cubism and clears out the corners: The lower left features thick-flickered strokes hovering over a thin-wash ground, a delicious lesson from Braque.

There is a clear map your eye follows in “Woods.” But it’s self-evident — you can’t miss it. Dodd, after all, isn’t trying to hide anything.

Two key passages reveal how the artist is helping us find our way. The dark Siena tree tip reaching up in stark relief over the whitest vertical trunk marks the center axis of the image — a starting point that holds your body in place. In the upper left is a branch that reaches back to the fallen tree; Dodd has cleared a visual path along it by masking out the green canopy behind the branch with sky white strokes.

This calm but complex painting is a Maine woods masterpiece.

Dodd’s vast range reminds us that style isn’t just the look, but the logic of a picture. Her fascination with windows, for example, mobilizes sophisticated ideas about vision, space, framing (in the theory sense) and the perspective of the painter, both physically and culturally.

“Door, Staircase” (1981) gives us the narrow, compressed and practically vertical space of an old Maine back staircase. The open door matches the support (linen, not canvas) from its corners to the depicted opening, a spatial gesture you can’t help but feel.

“Sunset at Quarry” (1995) reveals the geometrical underdrawing used to blow up the image from the tiny panels Dodd paints on site. (This is a potentially misleading aspect of the show: Its large canvases are not Dodd’s typical output). The repeated four lines of symmetry become part of the painting’s geometrical logic starting in the lower corners.

Dodd probably most stands out as a colorist, but her visual intelligence shows best in her endemic dovetailing of spatial structure with surface design.

The only works I haven’t cottoned onto are the large compositions with multiple nudes. Yet with them, Dodd is following my all-time favorite painters — Matisse, Cezanne and Manet — so maybe I just don’t get them yet.

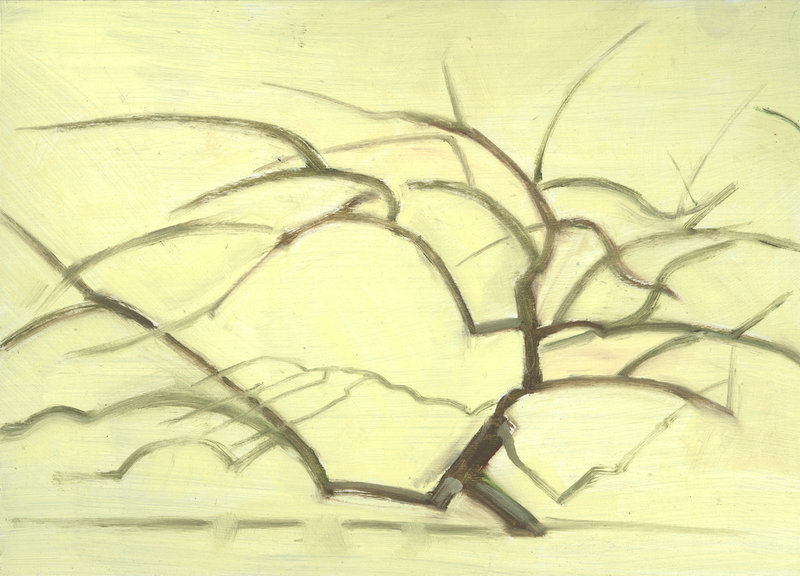

One of Dodd’s greatest inspirations appears to be early Mondrian; specifically, Mondrian’s trees.

“Catching the Light” is punctuated by 14 of Dodd’s usual tiny panels. Two of these show the same plum tree in 2012 and 2008. The later piece enters the image from the trunk and twists off into the composition through space, color and light. The earlier image maps out its own formal surface stroke by stroke, like a musical map of the surface punctuated by spaces Dodd put back into the shadow/horizon line. I could look at this pair for hours.

Dodd’s no-nonsense approach is free from fanciful affect. Seemingly effortlessly, like that good armchair, her art shows us that the everyday world is a place of worthy and intelligent beauty. Underlying it all is Dodd’s practical, dedicated and work-attained Maine art ethic; after all, that chair has a job to do.

Lois Dodd is a great painter. “Catching the Light” makes that clear.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.