When sculptor Harry Stump of Warren died at age 82 on an early fall day in 1998, he left behind a population of athletes and other lithe and graceful figures he had created to mark the human race. It is a legacy to treasure.

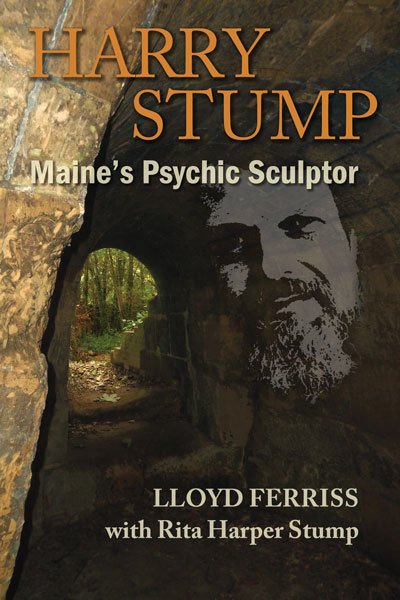

Now, 14 years after his death, Maine journalist Lloyd Ferriss has enriched that legacy with a portrait of Stump created in words. “Harry Stump — Maine’s Psychic Sculptor” deserves to be noted. And it deserves to be read as a meaningful attempt to fix Stump in the world of 20th-century art.

Stump is no local boy who grew up with the sounds of Rockland and Camden and other midcoast Maine communities in his ears. At the beginning, he saw life on the other side of the Atlantic, born and bred in Heerlen in the south of Holland near the Belgian border. It was a quiet place in a quiet time when families could plan for their children in peace. And Stump’s mother, Gertudis, planned ardently for him to become a priest. With her strength of will, it seemed to be a plan very much on track.

Yet control of the future lay in other hands. Ahead of Stump awaited years of German occupation of Holland and keenly dangerous experiences — “three imprisonments and torture by the Gestapo” — as a member of the Dutch Resistance.

That Stump survived this period, ending in the fall of 1944, and managed even to serve for a time with American forces in the Battle of the Bulge adds intrigue to this unusual artist’s story.

So too does his move to New York City, assisted by his sister Gerry, where he suffered poverty that reduced him to living on a glass of milk and a peanut-butter sandwich each day and sitting in Grand Central Station to stay warm at night.

Stump survived poverty as he had survived the war, turning inward for strength and simply enduring. As he would write later, “Coping with life in New York took all the strength I had. Even today I wonder how I hung on. The English language with its mystifying grammar frustrated me. I regretted coming to America and wished I’d gone to New Zealand or Australia instead.

“Mixed with these thoughts was guilt about my survival. I’d relive in my mind the close calls I had during the war, and wonder what right I had to survive when so many others were dead. I became so depressed eventually that nothing seemed to matter.”

Throughout this period, Stump kept his psychic sensitivity to himself, knowing it could make others uneasy. This self-imposed censorship failed him, however, at a party in New York when a loudmouthed critic ridiculed the idea of extrasensory perception and dismissed psychics as frauds.

“Finally,” Stump wrote later, “I’d had it. ‘If ESP is nonsense,’ I said, ‘how do you account for my knowing that you have a photograph of a man in your pocket?’ I then described the person in the photograph, including his habits and favorite sayings.”

Stump felt badly about breaking his own taboo, but what he called “the indiscretion” changed his life.

The mother of one of the guests at the party, Alice Bouverie, introduced Stump to Dr. Andrija Puharich, director of research for the Round Table Foundation at Glen Cove on Penobscot Bay. Puharich offered the sculptor a job, and he was lifted out of poverty into his life’s work. He was also lifted into the company of Aldous Huxley, who became a major influence upon him.

It was in this open and welcoming environment that Stump developed his own sculpture and sharpened his own psychic awareness.

Ferriss explores all of these aspects of a most interesting artist. His book, prepared with Stump’s widow, Rita Harper Stump, and Stump’s unpublished autobiography, tells the story well. A single voice with a single point of view might chart a clearer path, but that’s another book for another time.

Nancy Grape writes book reviews for The Maine Sunday Telegram.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.