“Worldview” at the University of New England Art Gallery in Portland might be a philosophical mess, but it’s an interesting and worthy exhibition. The third installment of the four-part exhibition “Maine Women Pioneers III” raises more questions than it answers.

That mess, after all, is too important socially, culturally and philosophically for us to let it be whitewashed into oblivion. And yet someone will inevitably ask: “Why a show about women artists in 2013; haven’t they caught up already?”

My favorite preemptive response is Edgar Allen Beem’s steely brave but quip-witty catalog essay, in which he discusses artists such as Anna Hepler, who turned down the invitation to participate to avoid being pigeonholed as a woman artist, and others such as Lauren Fensterstock, who were conflicted about the project but didn’t refuse. Beem’s real-time critical awareness is a welcome alternative to the usual self-congratulatory undertone of exhibition catalogs.

While all three installments of MWP have put forth a decidedly introductory (rather than encyclopedically complete) approach, viewers — with the hot-off-the-press catalog in hand — no longer have to forestall forming conclusions about the series. And for a show dedicated to raising questions, this matters.

“Worldview” is the curatorial brainchild of UNE Art Gallery director Anne Zill; Gael McKibben, who co-curated the previous MWP exhibitions years ago when the gallery was Westbrook College’s Payson Gallery; and gallerist Andres Verzosa.

When I found myself wondering why welder/sculptor Melita Westerlund was included rather than say, welding maestro/Colby College professor Harriet Matthews, things immediately got interesting. My thinking about who could (or should) have been included in the series — and why — was probably just what the curators wanted.

This questioning strategy is mirrored directly by Natasha Mayers’ group of painted vanity license plates about institutional unfairness. From the states of “Corporate State,” “Drone State,” etc., they feature messages such as “2BG-4JL” or “SRVA-LNCE.”

Because they are painted in a casual hand on cardboard with approachable wit, you find yourself trying to one-up Mayers by making up your own — and that’s precisely what she wants. Mayers isn’t above the audience; she wants to be our catalyst. Her empowering message is, “You CAN do this!”

Mayers’ work hangs next to Judy Glickman’s photographs. While these might look dissimilar, Glickman’s poetically forceful photo of a woman — reflected in the glass in front of the ovens at Auschwitz — also reflects a certain unassailable weight back onto Mayer’s anti-war works. Together, Mayers and Glickman compel us to open our eyes and take political action.

The ground floor is a bit too densely hung, but until there is handicapped access to the architectural gem’s other levels, I can live with that.

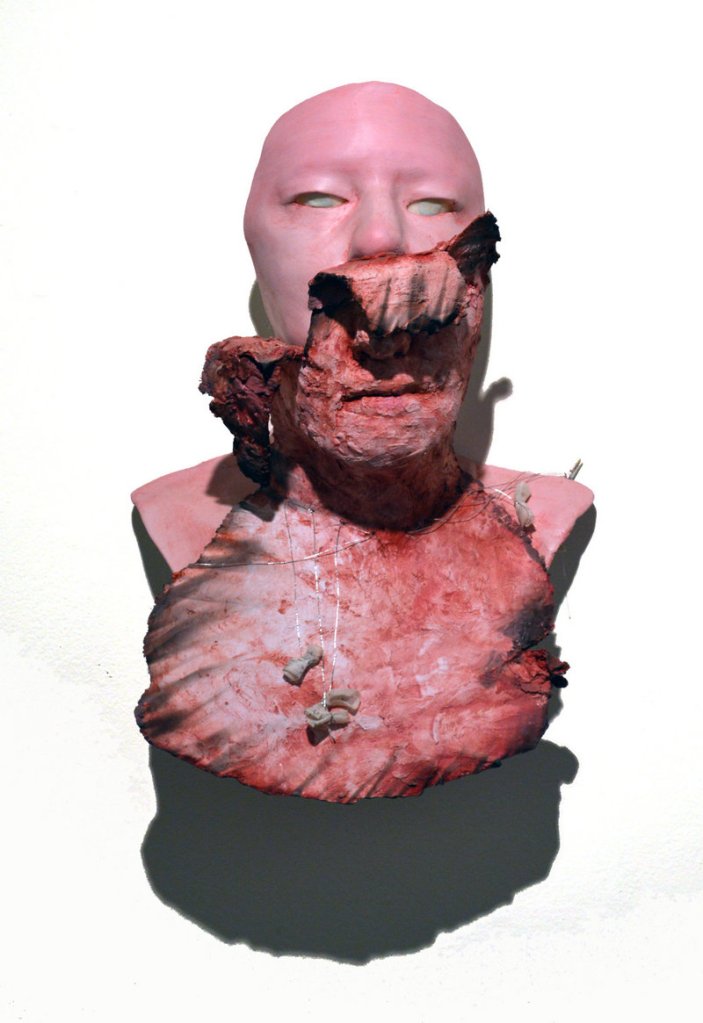

The strongest work on the first floor is Arla Patch’s powerful “Burning Off the Past” — a wall-mounted plaster bust that molts a scarred outer skin to reveal a painfully raw but fresh figure underneath.

The still-dead white eyes are just beginning to come back to life, and we see the pulled silver threads of broken seams falling away. The tips of the threads bind bits of charred cloth — uncomfortable proof of past (but not forgotten) atrocity.

As someone who grew up in “Elm City” (Waterville), I find Judy Allen-Efstathiou’s “Tree Museum” works particularly moving. Her thoughtfully beautiful drawings of elms, chestnuts and other blight-devastated trees reveal an unusually compassionate world view.

Allen-Efstathiou illustrates how the world can change radically for the worse if we aren’t careful. She reminds us about the fungal blight that appeared 100 years ago near Yankee Stadium and spread from the Bronx, destroying 3 billion chestnut trees between Appalachia and Maine.

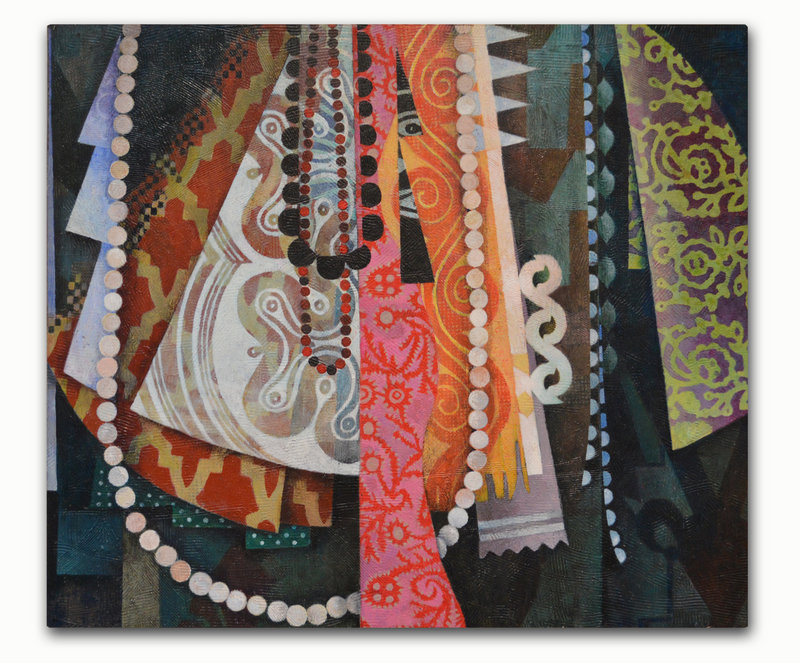

Together, the work of Abby Shahn, Alice Spencer and Westerlund (colorists all) looks great in the upper gallery. I particularly like Spencer’s elegant and beautifully finished cubist-like paintings of textiles. These paintings quietly take on the art versus craft question next to Spencer’s not-so-quiet, quilt-like collage (which is, unfortunately, upside-down in the catalog).

Westerlund’s sumptuously colorful coral reef wall reliefs, however, are the stars of the show. Not only are they visually exciting and handsome, they are technically unusual (cotton fiber constructions over a metal armature), and they deliver a passionate warning about the Earth’s coral reefs that is electrified by Allen-Efstathiou’s lessons about human-driven environmental catastrophe.

Dovetailing with their cautionary environmentalism is Kate Cheney Chappell’s nature-inspired mysticism. Her seaside paintings find spirit in seams and tiny, overlooked places.

Chappell’s illusion- and camouflage-oriented floor installation of stones and sea-life prints — in standing mirrored Mylar rings — might be the most original and meditatively fascinating piece in the show.

“Worldview” is a largely successful show that is definitely worth visiting.

The challenge at this point, after all, is not to prove that women can make important or influential art or — like Colby’s Sharon Corwin, the Center for Contemporary Art’s Suzette McAvoy or UNE’s Anne Zill — successfully lead cultural institutions, but rather to de-compartmentalize women artists.

It’s a strange process — less like starlets ascending to limelight heights than a diver decompressing from the dark depths to reach the breathable sea-level air under a sunlit sky.

“Maine Women Pioneers III” takes on an enormously important subject — maybe not perfectly, but with sufficient grace and ample dignity. After viewing it, you might ask: “Where is the feminism?” But “Worldview” is less about diversity than transcending adversity. It is about perspective — which, sometimes, is an ever-shifting target.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.