We sprang for a whole grass-fed Crystal Spring lamb for the first time this past winter. While I managed to fit all 35 pounds of cuts into my fridge’s bottom-drawer freezer, we’ll still be enjoying lamb at least once a week well into spring. That’s a good thing, because for me there’s something nostalgic about this underappreciated meat, especially as the freshly shorn ewes and newborn lambs around us in Maine move out to pasture. When I was growing up, this spring holiday season was also the one time of year, at least from a culinary standpoint, that my Jewish and Episcopalian roots didn’t feel at war. Whether we were celebrating Passover or Easter (often both simultaneously), leg of lamb, or on rare occasions, a rack, was always the unifying centerpiece of a festive meal.

From our whole lamb, I’ve broiled cumin-and-cardamom-dusted loin chops, braised spicy coffee-rubbed shanks and caramelized addictive, Vietnamese-style lamb riblets. We’ve also learned to love the ultra-fresh offal: the steak-like hearts, the liver sautéed in a spicy curry and even the kidneys, first soaked in alcohol to remove that barnyard flavor, then pan-fried in butter. Sadly, lamb tongues weren’t part of the package. But for the family-friendly Passover seders we’ll attend this week, I’ll stick with tradition. I’ll finally serve the bone-in sirloin leg roasts that have been occupying precious freezer space. Also, with kids in mind, last Passover I started a new tradition of lamb-quinoa meatballs.

Ground lamb is just as versatile as ground beef. It’s easier on the palate – and wallet – than other preparations. Instead of ordering a whole lamb next year we might just stock up on pounds of ground – and those tender hearts, which longtime grass-fed, organic-certified Apple Creek Farm sells for $4 a pound at my Brunswick indoor farmers market. And more of those lamb breast riblets (aka Denver-style ribs), which have a surprising porky, sparerib quality. We’ve also found rosemary-garlic mutton sausage – from sheep at least 1 year old – to be surprisingly lamb-like and delicious.

Here in Brunswick, Crystal Spring Farm’s Seth Kroeck, his son Griffin, 10, and daughter, Leila, 8, enjoy their also soon-to-be certified organic, 100 percent grass-fed ground lamb in spaghetti Bolognese sauces, burgers, meatballs and, of course, baked under mashed potatoes in Shepherd’s Pie. Mom Maura Bannon is a vegetarian. “It’s the (lamb) gateway drug,” says Kroeck, who never tried lamb when he was growing up in the Midwest. “My kids don’t even blink about it. They’re 100 percent into it.”

At farmers markets, ground lamb is most in demand, says Jeff Burchstead of Buckwheat Blossom Farm in Wiscasset. Pricier chops with low ratios of meat to bone are a tough sell. These higher-end cuts should really be served medium rare, Kroeck says. Yet cutting into a still-purple center makes some people squeamish, plus grass-fed lamb can have a stronger flavor – it mellows with long cooking for the tougher cuts. Farms such as A Wrinkle in Thyme in Sumner have considered grinding all their lamb meat. Most goes into their Maine maple-sage sausage, great as breakfast links or crumbled atop pizza or into chili, say farmers Marty Elkin and Mary Ann Haxton.

Meatballs are now my go-to preparation. I first made prune-studded ones dipped in yogurt sauce after moving to Oregon in late 2008. Foodie friends there taught me to alternately roll lamb meatballs in black and white sesame seeds, for a striking, textured effect, and to tuck minted feta cheese inside the meatballs.

Oregon also really put quinoa on our radar. Particularly in the local food world, many friends there (as in Maine) had adopted gluten-free diets, turning to this protein-rich seed as substitute. Quinoa also happens to be kosher for Passover, a week when Jews forgo wheat and other grains. Thus, these meatballs were born. And since the Passover message is one of social justice, I’m relieved to hear the global quinoa boom may in fact help – not hurt as originally reported – poor Andean farmers as Western demand raises the price for their staple grain.

I’m comforted knowing the meat we so reverently prepare this holiday had a just life that undeniably did come to an abrupt end at a local slaughterhouse. Windham Butcher Shop processes Crystal Spring’s lambs, but the farm plans to switch to one of the state’s only two certified-organic abattoirs – Luce’s Meats or Herring Bros. – so they’ll be able to label the meat organic. Yes, eating meat involves death, but here it’s done as humanely as possible. Compared to the fate of most animals on our dinner tables in America, these local lambs face far less stress at the end of their lives. Of course, on-farm slaughter would be even less frightening for the animals – but in Maine, chickens are the only animal that may be slaughtered at farms and sold to the public.

“It’s so special and valuable to know so much about them,” Kroeck says, “that they’ve lived a good life, and they’re going to taste great when they come back.”

Also, the lambs have a longer life than you may think, because “spring lamb” is often a misnomer. We’re not eating those cute newborns, but rather ones born last spring (or less commonly in the fall) and slaughtered between 6- to 9-plus months of age.

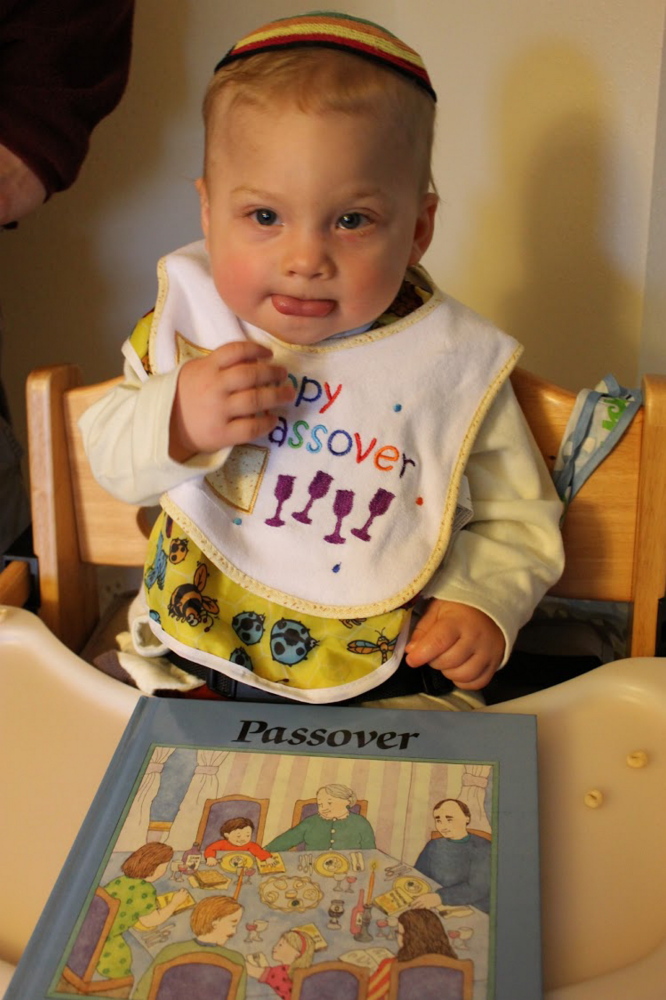

Unfortunately, my once-intrepid toddler Theo now rejects lambs, both in the barns and on the plate. He did warm up to the animals recently at Crystal Spring Farm, as we watched contented ewes chew the cud while their newborn lambs suckled from prominent udders. Indeed, it would be a welcome Passover miracle to see my little boy again enjoy lamb and the other meats he once craved.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.