While brokers tempt investors with derivatives, hedge funds and collateralized debt obligations that are able to zip around the globe at lightening speed, venture capitalist Woody Tasch wants to see a return to a slow but steady gold standard with more long-term security than a blue chip stock.

His plan? Invest in soil fertility.

Tasch, who lives in New Mexico, is the leading figure in an emerging movement called slow money. The concept is catching on across the country, including here in Maine.

Slow money brings together socially-responsible investors with proponents of local and organic food, in a collaboration aimed at fundamentally shifting how money moves through the economy and where it gets invested.

“There’s a growing awareness about the importance of local food,” Tasch said in a recent interview. “But there’s also a broader concern from investors that the global financial system is out of control.”

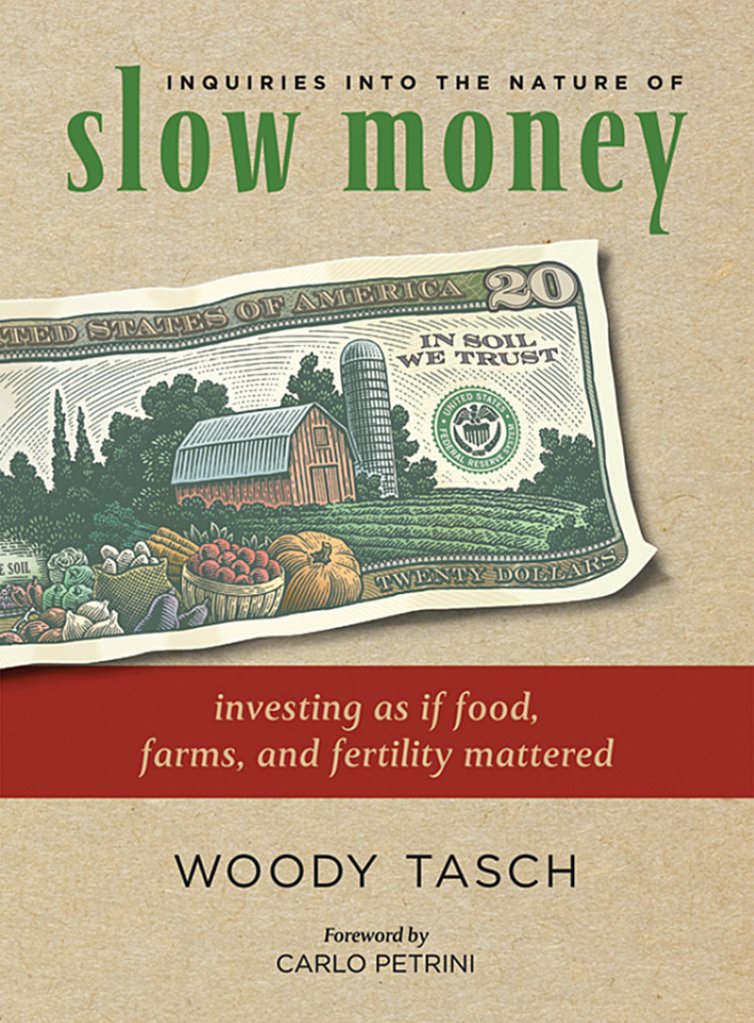

In the seminal book on the subject, “Inquiries Into the Nature of Slow Money,” Tasch writes: “The problems we face with respect to soil fertility, biodiversity, food quality, and local economies are not primarily problems of technology. They are problems of finance. In a financial system organized to optimize the efficient use of capital, we should not be surprised to end up with cheapened food, millions of acres of GMO corn, billions of food miles, dying Main Streets, kids who think food comes from supermarkets, and obesity epidemics side by side with persistent hunger.”

Slow money also seeks to overcome the funding obstacles faced by small-scale food producers who compete in the global financial market, which favors mega-farms and consolidated food manufacturers.

MAINE ENTERS THE SLOW LANE

Come October, Jeffrey Wolovitz needs $10,000 to buy 15 tons of soybeans from a Maine farmer, but he lacks the necessary cash. Wolovitiz and his wife own Heiwa Tofu in Lincolnville, where in two years the company has gone from producing 300 pounds of tofu a week to 1,000 pounds a week.

Last year, when it was time for Heiwa to buy its yearly stock of locally-grown soybeans, the Wolovitzes went to a bank for a line of credit, but could only secure a quarter of the capital they needed. On Thursday, Wolovitz will head to a meeting of Slow Money Maine to see if he can find Maine investors willing to provide him with a loan to cover the soybean purchase.

“Part of what I’m looking for at the meeting is feedback on how to structure” this line of credit, Wolovitz said.

The first national gathering to talk slow money took place last fall in Santa Fe, N.M., and included a handful of folks from Maine. Bonnie Rukin of Camden was among the participants, and when she returned to the state, she called a meeting in January to kickstart a Slow Money Maine chapter.

Since then, the informal group has met every other month, with the most recent meeting attracting 40 participants. Tomorrow at the Viles Arboretum in Augusta, another meeting will take place.

“Right now, there seems to be a lot of momentum building,” Rukin said. “The interest has been phenomenal.”

Thursday’s meeting will include a series of presentations from players in Maine’s local food economy.

Nicole Witherbee, who heads the consulting firm Policy Edge, plans to discuss an ongoing research project examining what local food distribution and processing projects are most needed and would make the most sense for Maine’s socially responsible investors to support.

So far, an intern on loan from the Maine Department of Agriculture conducted five in-depth interviews with Maine farmers. Witherbee is seeking funding to conduct 59 more interviews and produce a paper survey that would be mailed to 1,000 farmers.

Witherbee has been working with Maine social activist and philanthropist Eleanor Kinney, who has already assembled a group of willing investors who just need an investment vehicle.

“We’ve been meeting with private investors and banks to figure our what structures could be created to use that money once it’s put forward,” Witherbee said. “The idea is, you take capital out of areas that don’t feel as good and put it into the slow food movement.”

Russell Libby, who heads the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, will offer a report about how Slow Money Maine should be organized.

“We’re proposing a steering committee structure of five to nine people to guide the organization for the next six to nine months,” said Libby, who is representing a subcommittee that considered the issue.

Down the road, if Slow Money Maine wanted to establish a loan fund, for instance, it may need to adopt a different legal structure, Libby said.

SLOW MONEY IN CIRCULATION

It’s easy for everyone from average Joes to institutional investors to pour money into companies like Monsanto, a frequent target of attacks by food security and local food activists. But should an investor want to finance a Maine farm that needs a new greenhouse or a local food processor that wants to expand, it becomes much more complicated.

This is the discrepancy the slow money movement hopes to rectify. As organizers explore new ways to connect Maine capital with Maine farmers and food producers, a handful of slow money projects already operate in the state.

For the past 10 years, Coastal Enterprises Inc. has offered loans of up to $35,000 through its Organic Revolving Loan Fund to farmers who work without chemical pesticides or fertilizers. Last fall, it added another fund to its portfolio called the Maine Farm Business Loan Fund, which also has a cap of $35,000.

“We are more risk-tolerant than a lot of other lenders,” said Gray Harris, director of agriculture at Coastal Enterprises. “But we require a certain amount of due diligence. We have an understanding of the unique qualities of agriculture and farming.”

MOFGA is in the second year of administering its Organic Farm Loan Fund in collaboration with Bangor Savings Bank. This year, it provided nine low-interest loans that range from $5,000 to $25,000.

MOFGA’s Libby said the loan recipients tend to be people who wouldn’t qualify for traditional financing. The loans are secured by money from individual donors and MOFGA’s endowment held in certificates of deposit by the bank. The Coastal Enterprises loans are funded by grant money.

Investors can support the MOFGA loan fund by placing assets on deposit with Bangor Savings Bank, but there’s no way for individuals to invest in the Coastal Enterprises products.

While these micro-loan programs do fill gaps in the current financial system, agricultural projects requiring larger amounts of capital aren’t served by these funds.

For instance, Libby points out that “it’s really challenging to get a loan to buy a farm if you haven’t already farmed.”

On the national level, Tasch, who will be on hand for this year’s Common Ground Country Fair in September, said the slow money nonprofit he heads is investigating the creation of municipal bonds to fund local food initiatives.

“If we’re successfully able to bring some to market, it will open the floodgates,” Tasch said.

connecting local investors with local food producers, the movement aims to funnel capital to small-scale, organic agriculture. At its root, the concept seeks to bank on the healthy soil that is built and maintained by sustainable farming methods and is too often degraded by chemical-intensive farming methods.

“We’re lucky in Maine to have a lot of solid groups in support of local, sustainable food systems,” Rukin said. “Where some of these world issues are so overwhelming, food is where we can make a difference.”

Staff Writer Avery Yale Kamila can be contacted at 791-6297 or at: akamila@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.