MONHEGAN — A hundred years ago the biggest news in the art world was the Armory Show, an international exhibition of modern art that opened in New York on Feb. 17, 1913.

It was the first time American audiences who did not travel abroad could see for themselves the experimental ideas of the European avant-garde.

For a country that had fallen deeply in love with realistic depictions of tranquil country scenes, modern art proved challenging, difficult and radical.

Broadly defined, modern art included any works that favored experimentation over tradition. It trended away from narrative scenes and relied more an artist’s ability to express his or her ideas with a new visual language.

In today’s world, it’s the norm and hardly radical at all. But a century ago, when trends sometimes took years if not generations to catch on, modern art had everybody talking.

This summer, the Monhegan Museum dedicates its exhibition space to Monhegan artists who were part of the Armory Show and those who were influenced by it. The exhibition, “A Spirit of Wonder: Monhegan Artists and the 1913 Armory Show,” is on view through Sept. 30.

Robert Henri was at the center of the modern movement and at the center of Monhegan. He first came to the island, which is known for its high cliffs, deep woods and quaint fishing village, in 1903. He promoted it to his city friends as a magical place full of wonder, surprise and intrigue, and a perfect playground for fostering new ideas.

Five years later, he organized what Monhegan Museum director Ed Deci calls “a somewhat rebellious exhibition” of paintings by his colleagues, referred to as The Eight. The exhibition did not garner a lot of attention, and the group re-formed as the Association of American Painters and Sculptures.

It was that group that organized the Armory Show in the winter of 1913.

Modern art came to America with that exhibition, which traveled from New York to Chicago and Boston. Although the American artists were largely overshadowed by their European counterparts, Maine, and specifically Monhegan, had a significant presence in the Armory Show, said curator Emily Grey.

Indeed, there was one painting in the show with Monhegan in the title, Edward F. Rook’s “Grey Sea, Monhegan.”

The exhibition on view this summer features a few works by Monhegan artists who participated in the Armory Show, but mostly it includes paintings by a broad range of Monhegan artists who attended the Armory Show and were inspired by it.

Grey has assembled an exhibition that attempts to document the influence of the most important art show of the 20th century — and held in our country’s largest cities — on an island community tucked 12 miles off the Maine coast and inhabited largely by fishermen, their families and an extended community of seasonal visitors.

“There is no way to underestimate the influence of the Armory Show on art in America,” she said. “Even a place like this, remote as it is, was touched by it.”

That’s because Monhegan is still, in an unlikely way, at the center of the art world. It remains, as it has been since Henri began talking about it early last century, one of the most interesting places in America to explore and to paint, because of its scenery and the casual pace of its lifestyle.

We can see the impact of the Armory Show on the work created by the Monhegan colony of artists, starting with Henri and his prize pupil George Bellows, and extending on down through the years to artists like Joseph DeMartini, Edward Hopper, Emil Holzhauer and Leon Kroll.

‘A LITTLE MORE EXPERIMENTAL’

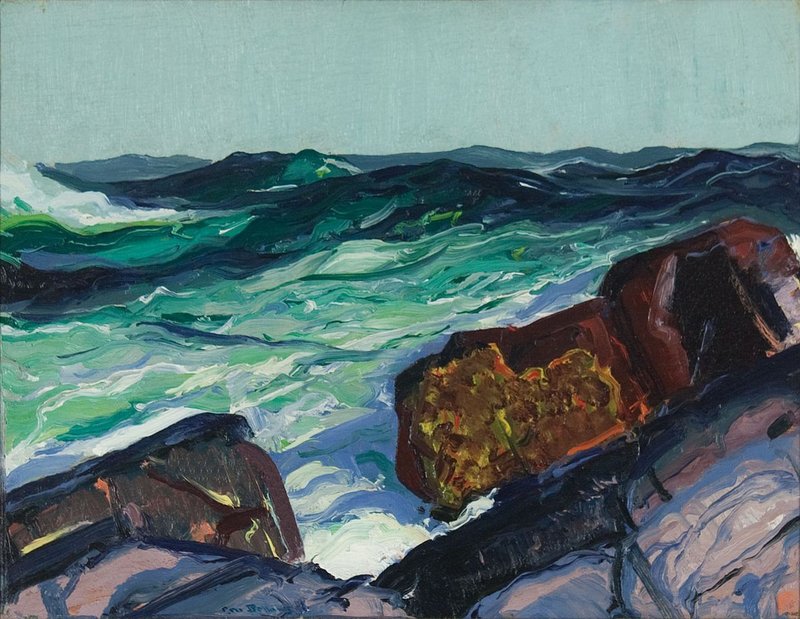

Grey cites a painting by Bellows, “Iron Coast, Monhegan,” as an example of the influence of the Armory Show.

Bellows saw the paintings in New York that winter, and returned to the island in the summer to begin a new season of painting. It’s fair to assume a direct influence of the Armory Show is his use of bold colors and abstract forms.

This is not a painting that is out of place among works of realism. Indeed, there’s no question what we are looking at: The churning surf runs hard against the darkened rocks. But the forms are more abstract, the colors exaggerated.

Bellows seemed less concerned about representing what he saw in paint, and instead painted what he felt.

The modernist influence can be seen in the composition of the painting. The loose, diagonal shapes of the rocks in the foreground create tension with the action of the painting, which is the sea itself.

The viewer is given a deeper sense of the artist’s emotional response to the scene than a specific rendering of the site, Grey said.

“You can start to see how he is being a little more experimental,” she noted.

Along with Henri and Bellows, Kroll also exhibited his paintings at the Armory Show, and put his lessons to work out on the island. He was trained academically, and fell under the influence of Cezanne while studying in Paris in 1909. His painting, also from 1913, “Sunlit Sea,” reflects Cezanne’s method of building form through color.

“The warm, earthy reds of the sun-drenched rocks advance and the blue-green surf recedes, creating depth, while the vigorous, thick brushstrokes acknowledge the two-dimensionality of the surface of the painting,” Grey writes in the exhibition catalog.

WORLD COMES TO THE ISLAND

As the century moved through the Depression and World War II, the influence of the European modernist movement became more evident, and not just on Monhegan.

Because of the worldly nature of the artists who inhabited the island — they came then for the same reasons that Henri and Hopper came, which was to get away from the city — the work they created there mirrored the work they saw in New York, Boston and overseas.

As modernism became more accepted generally, it manifested itself in the work created on Monhegan, Grey said.

DeMartini’s “The Wreck of the St. Christopher” from 1949 provides a dramatic example.

He was a widely accepted artist, winning great reviews and acclaim in New York and elsewhere. He cited the Armory Show for his interest in art. “The Wreck of the St. Christopher,” which is now in the Monhegan Museum collection, ended up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York the year after it was painted.

DeMartini came to Monhegan over two decades beginning in the 1940s.

Grey includes several paintings by DeMartini in this show, most of them untitled. “The Wreck of the St. Christopher” is noteworthy because of its exaggerated form.

The Gloucester, Mass., dragger caught fire and ran aground. The crew escaped unharmed. DeMartini depicts the boat splintered apart, almost cubist in style, its deck splintered, the bow high in the air, parts flying here and there. It’s dramatic and direct.

A painting like this might be unimaginable on Monhegan a generation before. But by the end of World War II, this approach to painting had become the norm.

One more painting illustrates this trend. Louis Lozowick also painted on Monhegan in the 1940s. He was a Russian Jew, and came to the United States in 1906 to avoid persecution.

He studied with Kroll, and attended the Armory Show several times because of his fascination. He struggled to accept modern art, and admitted not understanding it.

Instead of giving up, Lozowick delved deeper, traveling to Paris, Berlin and Moscow. He met Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger and others, and came to embrace many different styles and approaches to art making during his life.

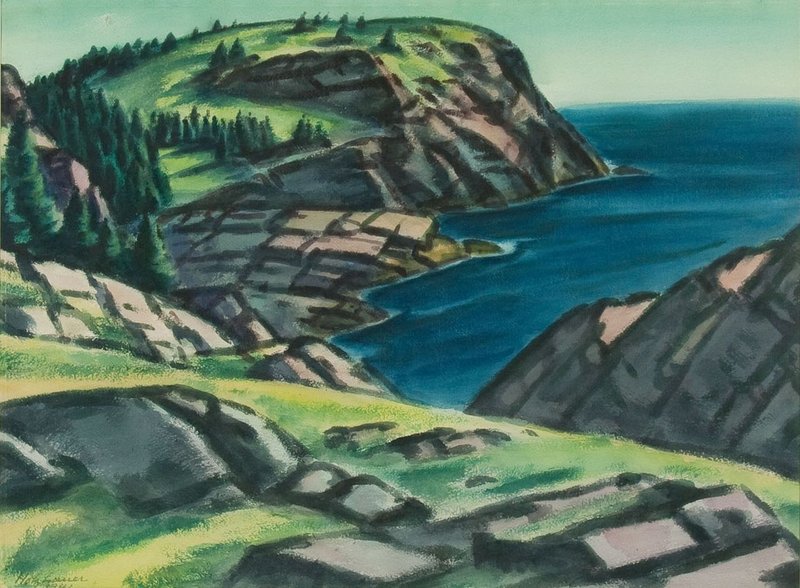

One of two paintings of his in the Monhegan show is “Pulpit Rock,” a depiction of a promontory on the island’s south end. It is widely reproduced, but Lozowick’s image is unique in that the rock formation, while not obscure, is almost faint. It feels soft, transparent.

Said Grey, “It’s probably the most unusual painting of Pulpit Rock you’ll ever see.”

Perhaps the message of this show is obvious in hindsight. Modernism came to Monhegan just as it came to the rest of the world: Slowly at first, with some reluctance.

But because of the persistence of a few who led the movement, within a generation it was accepted as mainstream.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.