OWNSHIP 8, RANGE 9 – In the middle of the North Maine Woods, Matt and Jess Libby inherited a century-old sporting camp — and a problem that could last that long.

When the fifth generation of Libby Camps owners begin welcoming deer hunters this week, there will be a lot of talk of the way things used to be.

“Deer season used to pay the bills,” said Ellen Libby, Matt’s mother and a part owner of the lodge. “Now we just do it because we’ve always done it.”

Deer season begins for all firearm hunters this week, but hunters won’t fill the eight main cabins at Libby Camps as they once did, nor the outlying 10 cabins.

Ellen Libby said business will be down 60 percent from the heyday of hunting there 20-30 years ago.

And the 120-year-old sporting camp that once employed eight guides during deer season will have just three this fall.

A declining deer herd in northern Maine is changing the storied tradition of sporting camps in the state’s northern forestland. And as the number of deer has plummeted, guides say so too has the number of deer hunters.

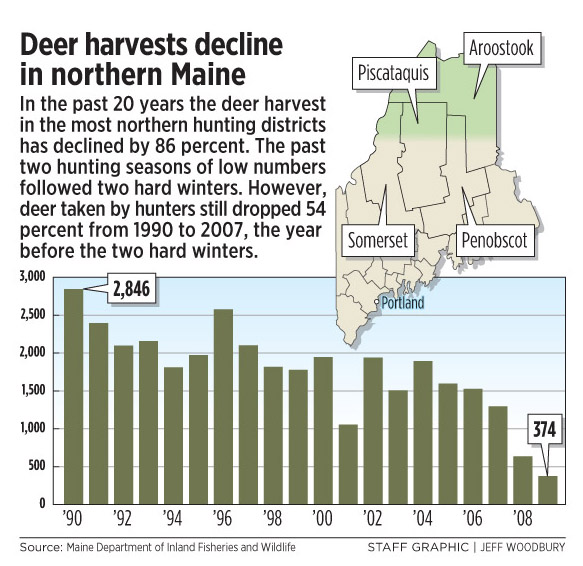

Twenty years ago, more than 2,800 deer were taken by hunters in the state’s most northern hunting districts. Last year there were just 374 tagged. And despite last winter’s mild snowfall, which is expected to help the whitetail, there may be no going back for the northern herd — or the rustic sporting camps that once drew deer hunters to Maine.

“We’re tickled we had a mild winter and people are seeing fawns. But it is what it is. People are seeing deer now. As far as the total harvest, I’m not expecting much of a bump,” said Maine deer biologist Lee Kantar.

As a result, most sporting camp owners in northern Maine are catering to different outdoor groups in order to stay in business.

Libby Camps is nestled among some of the state’s best wild trout waters and prime bird hunting territory. Not surprisingly the Libby family has built a successful business around catering to fly fishermen and bird hunters.

But meaningful deer hunts in which sportsmen at least see deer are becoming a thing of the past, Jess Libby said.

A few hours south or north, the story is the same.

At the northern end of Baxter State Park, Mt. Chase Lodge sits on a winding road that offers views of nearby peaks, including Mount Katahdin. But despite the choice hiking country and scenic park land, camp owner Rick Hill said hikers and leaf peepers don’t pay the bills.

Fortunately for Hill he got involved with the growing snowmobile business in northern Maine 30 years ago. In the past several years it’s been a godsend.

“There are about a million people in this state. Less than 25 percent of them live north of Bangor. The others don’t have a clue what it takes to survive here,” Hill said.

Hill believes the growing coyote population is central to the deer herd problems and should be eradicated by trapping.

Years ago, trappers with special permits were allowed to take coyotes through the winter to help the deer population. But in 2003 the Maine Attorney General determined the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife could be libel and face a lawsuit and so the practice was stopped.

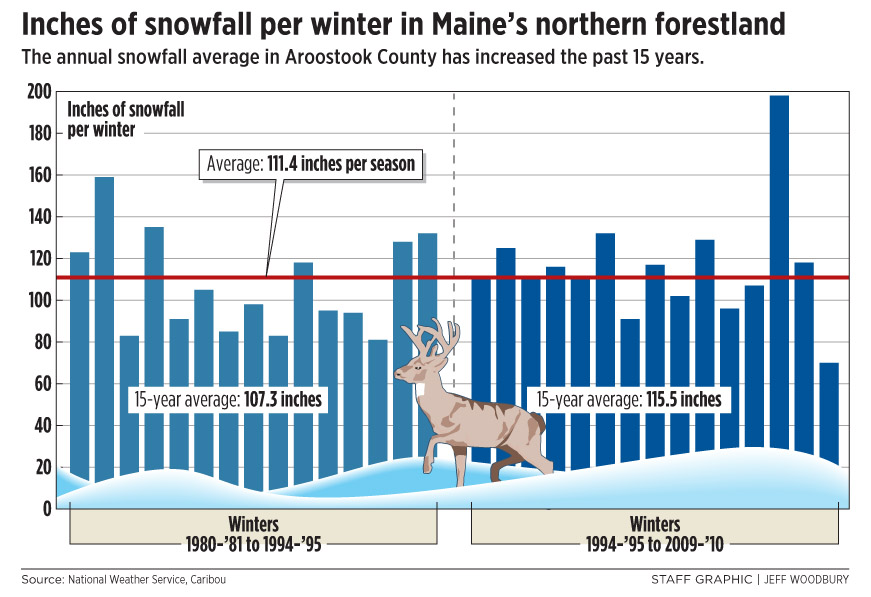

Hill said the deer population now doesn’t have a chance in this region, where 3 to 4 feet of snow is common.

“It didn’t solve the problem, but it kept it at bay. Now we don’t have that tool,” Hill said.

And at the very tip of Maine at Allagash Guide Service, Sean Lizotte sees other problems hurting the deer herd.

When the Master Maine Guide drives along the Allagash and St. John rivers in the winter, he sees people feeding deer, drawing them to busy roads where the hungry animals get hit.

And new logging roads in the woods drive up predation on deer, Lizotte said.

He pulls out a map showing new logging roads that have gone in around deer yards, making easy travel for coyotes.

Historic deer yards are protected by the state. These are the areas deer seek protection in deep snow.

But as the landscape changes, Lizotte has seen deer driven from these protective yards.

Years ago, Lizotte began catering more to canoeists in the summer as well as bear and bird hunters in the fall. These activities helped Allagash Guide Service stay in business after the deer hunting dropped.

An increasing bear population helped, Lizotte said. But as the forestland and its mix of wildlife changes sporting camps must change too, he said.

“To some extent we didn’t have any warning. But if you’re smart enough to look at the (changing forestland) it’s writing that’s been on the wall,” Lizotte said.

Staff Writer Deirdre Fleming can be contacted at 791-6452 or at:

dfleming@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.