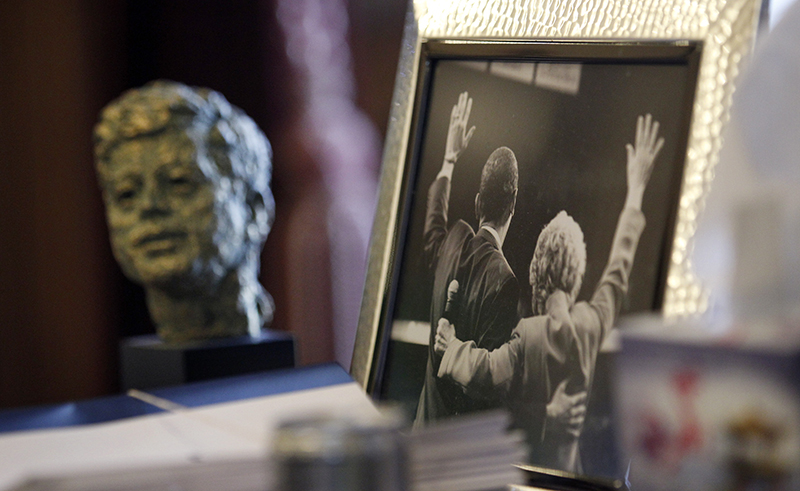

It has been 50 years since the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the life and sudden death of the charismatic young president is being examined again in all the voluminous detail befitting a major anniversary.

There are more than 100 new books set for publication, including one that speculates on what would have happened if he had not been murdered on Nov. 22, 1963, in Dallas.

Magazines such as Vanity Fair, The Atlantic and LIFE will produce special editions. Others are publishing lengthy essays. The New York Times freed up executive editor Jill Abramson to survey the books, past and present, and the Washington Post dedicated a Sunday opinion section to JFK, including a detailed recounting of the death of baby Patrick and “5 myths” about his beautiful wife, Jackie.

(She wasn’t exactly an heiress and actually needed the money she earned at her first job, a gossip photographer for the Washington Times-Herald.)

There is the movie “Parkland,” which tells the story of the staff at the hospital where Kennedy was pronounced dead. The Newseum in Washington will replay in real time the CBS broadcast coverage of that day in Dallas. Also on display there are intimate photographs of the young family taken by Jacques Lowe. Rob Lowe gets to play Jack in a National Geographic Movie.

And, of course, there is an app for that — a smartphone application that allows you to hear the Dallas police dispatches from that day.

“It’s too much and it’s not enough,” writes James Wolcott in Vanity Fair, because our bright future was stolen and replaced with diminished one. “History left us hanging.”

The gruesome murder of President Kennedy broke the heart of this country in ways that have echoed through the decades since. At the same time, the Camelot myth that grew to take the place of the man became a kind of analgesic.

The salesmen behind this multi-media re-examination of all things Kennedy would probably say that this onslaught is a way to honor the man — I would say the legend — and introduce him to generations of Americans who cannot say where they were on that day because they were not yet born.

But I am not sure the kids are paying attention.

The consumers of all this Kennedy stuff, I am guessing, will be those of us who can say where we were on that day. The generations who came after us don’t understand our wounded fascination with the assassination and the Kennedy tragedies that followed — the deaths of Bobby and young John.

And besides, the next generation has its own seminal moments — the explosion of the Challenger, 9/11 — just as our parents had theirs — Pearl Harbor.

Whatever evocative storytelling in whatever form this month will never convey the shock of the bulletin from Dallas, Walter Cronkite’s somber announcement on live television and the days of pageantry and mourning that followed. John-John’s salute, the widowed Madonna, the riderless horse.

And nothing can truly capture the nagging uncertainties about conspiracy and motive that still cling to the assassination five decades later. The grassy knoll. The magic bullet. The gangster’s moll. Lee Harvey Oswald’s time in Russia. A nobody strip club owner named Jack Ruby.

And I fear that what we felt then — the soaring promise of Kennedy’s youth, style and eloquence and then the hollowing out when we realized the violence we were capable of as a nation — I fear that those powerful lessons will be lost forever. Lessons that should be part of the formation of our national character.

“An assassination should be significant for more than its atmospherics,” Adam Gopnik writes in the New Yorker. “Kennedy’s should also matter for people who weren’t there, because something happened in America that would not have happened had Kennedy lived.”

We lost our innocence. That’s what happened.

We have lost our innocence a dozen times since John F. Kennedy was murdered. Kent State. The My Lai massacre carried out by American troops. Watergate. Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress. The weapons of mass destruction that never were.

But it is important to remember that first time. The day that marked the before and the after. The day everything changed.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.