ORONO — Playing for college football’s national championship is worth $18 million to each team. Advancing to basketball’s Final Four means $9.5 million to a school’s conference.

So what’s at stake, financially, for the University of Maine on Saturday when its football team hosts an NCAA playoff game for the first time in school history?

Small potatoes.

“There’s clearly a lot of benefits to advancing in the playoffs and winning the games,” said Steve Metcalf, deputy athletic director at the University of New Hampshire, UMaine’s opponent and a tournament team for a best-in-the-nation 10th straight year. “It does great things for the university and the athletic department and the football team … but there are no similarities between this and the bowl games” – those post-season appearances reserved for so-called BCS schools with 85 scholarship players, 22 more than teams in Maine’s category.

Last month the Black Bears (10-2) wrapped up their first outright conference title since 1965. They earned the No. 5 seed and a first-round bye in the 24-team Football Championship Subdivision national tournament.

Playing rival New Hampshire (8-4) at Alfond Stadium could benefit the university financially if ticket sales (more 5,500 had been sold before Friday) cover the $30,000 due to the NCAA for the right to host the game.

In any case, Maine’s post-season run – even if it continues all the way to a national championship game on Jan. 4 in Frisco, Texas – likely will help entice alumni to increase donations, improve the school’s reputation and be used as a recruiting tool. But it is unlikely to produce a huge windfall for the school’s athletic budget.

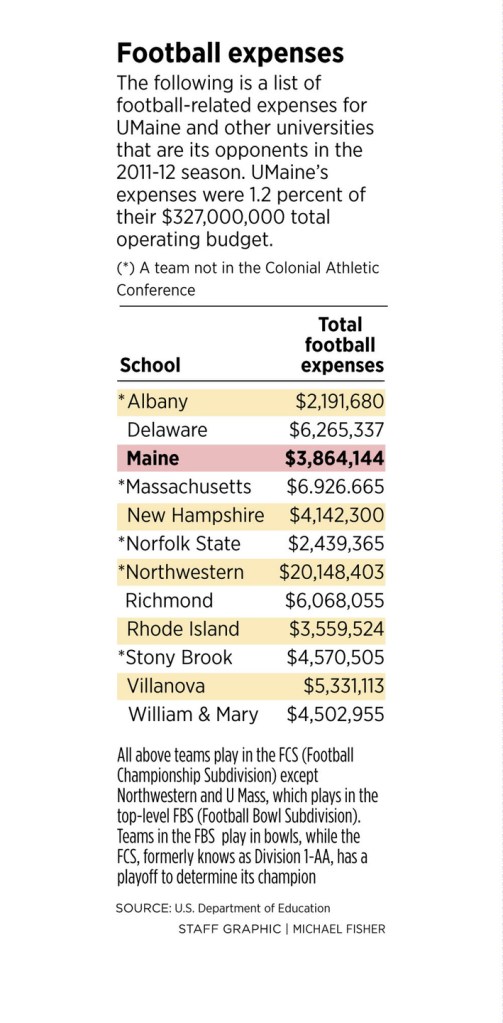

To understand why, it’s important to first understand the two tiers of Division I college football. The top tier is called the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and includes programs such as Alabama, which spent $41.6 million in the 2011 season, the most recent available on the U.S. Department of Education’s Equity in Athletics Disclosure website, and brought in $88.7 million.

The second tier is called the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS). It consists of Maine and about 120 other schools, only four of which reported a financial surplus from the 2011 season. And even then “those numbers are pretty small,” said Dan Fulks, an NCAA research consultant and professor of accounting at Transylvania University in Lexington, Ky. “The average profit was $200,000. The average football loss is $2 million.”

Fulks studied the revenues and expenses from all NCAA Division I athletic programs between 2004 and 2012 and produced a report of more than 100 pages filled with tables and broken into tiers (FBS, FCS and schools without football), sports and genders. Among his takeaways: Not one FCS athletic program ran a surplus and most FBS programs – except those involved in the five big-money BCS bowls with payouts of $17 million-$18 million – actually lose money by going to a bowl game.

‘AN EXTRA HOME GAME’

The only time Maine took part in a bowl game was in 1965, when the Yankee Conference championship squad faced East Carolina in the Tangerine Bowl and lost 31-0 in Orlando, Fla. The Tangerine Bowl eventually morphed into the Florida Citrus Bowl before becoming the Capital One Bowl, which is now played on New Year’s Day and cut checks of $4.55 million to each of its 2013 participants, Georgia and Nebraska.

That’s more than Maine spends on its entire annual football operation, including all coaching salaries and all 63 scholarship equivalencies.

Instead of post-season bowls, FCS schools take part in a playoff system with only the championship game played at a neutral site.

The entire payout for hosting a playoff game goes to the NCAA, which uses the money to help cover travel expenses, lodging and meals for the tournament’s visiting teams.

Maine was invited to bid on the right to host each playoff round, with a minimum guarantee to the NCAA of $30,000 for Saturday’s game, $40,000 for a quarterfinal and $50,000 for a semifinal.

“Basically, it’s an extra home game,” Fuchs said in a phone interview. “If you make money on your home games, it’s a good thing.”

According to records provided by the university, Maine spent a little more than $32,000 to put on five home games in the 2011 season and took in $104,500 from ticket sales and $4,700 from concessions and programs, for a per-game profit of about $15,440. So making a profit Saturday would be an achievement.

“For all those involved in the bid process,” Maine Coach Jack Cosgrove said of his university colleagues, “we’re very grateful to them for sticking their necks out and probably their pocketbooks as well. Now we hope to take advantage of the fact that we have a unique opportunity, something that’s never happened on this campus before and something that could be very, very exciting.”

UNH EARNS REMATCH

Maine lost its final regular-season game at New Hampshire, 24-3, two weeks ago. That gave the Wildcats an at-large bid to the tournament. They capitalized by routing Layfayette, 45-7, in a first-round game last weekend to earn the rematch with Maine.

The winner of the Maine-New Hampshire game plays a quarterfinal game against the winner of No. 4 Southeastern Louisiana (10-2) and two-time national finalist Sam Houston State (9-4). Should Maine and Sam Houston both win, the game would be played in Orono on Dec. 14.

Winning, of course, brings its own rewards, even if they don’t always show up on a spreadsheet. Just ask Mike Hodgson, a former player and assistant coach for the Black Bears who currently serves as the assistant athletic director for development. He helped put together Maine’s tournament bids and also helps with alumni donations.

“Donors like winners,” Hodgson said. “They like to be associated with winning programs. Now, we’ve got some incredibly loyal donors who will donate to you no matter what. But when you’re 10-1 (the best start in school history), people come out of the woodwork that you haven’t heard from in a long time and like what you’re doing, and like their alma mater’s name on the TV in California, and it makes them feel good.”

Beyond game-day considerations, a long tournament run could prove beneficial in recruiting top prospects, who naturally want to play for successful programs.

“The name gets out more,” Cosgrove said, “but in all honesty, we haven’t moved our location. It’s still going to be a challenge for us, for our coaches to recruit, because we’re not down the street and that’s never going to go away. But it’s certainly made easier by the fact that we’ve had the success we’ve had.”

Glenn Jordan can be contacted at 791-6425 or at:

Gjordan@pressherald.com

Twitter: GlennJordanPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.