Looking sharp in a charcoal gray suit and smiling broadly, Muktar Hersi held up his citizenship certificate to a cheering group of supporters at Portland High School, then made a gesture of dusting off his shoulders.

The truck driver from Auburn explained that the gesture symbolized getting rid of what he’d left behind, breaking with a painful past and starting anew in a land of opportunity and freedom.

“I’m at the top of the mountain,” said Hersi, who fled civil war in Somalia that claimed his brother’s life.

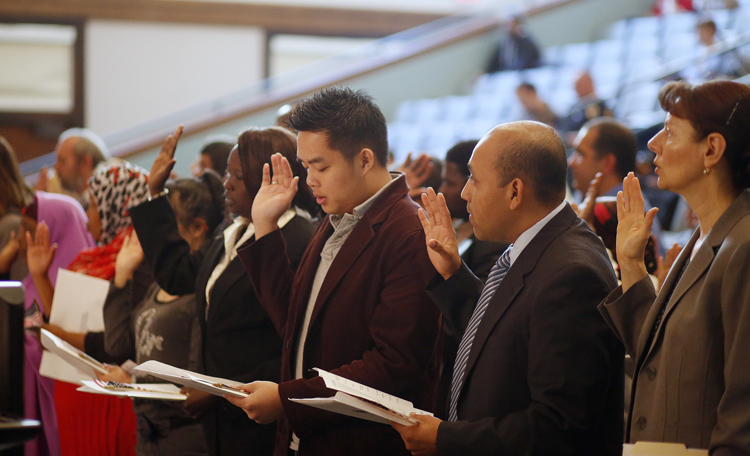

Hersi was among 45 people born in other lands who took the oath of allegiance Friday and became naturalized as U.S. citizens. They swore to defend the country and the Constitution, with arms and with civilian works, if called on.

The naturalization ceremony included immigrants from vastly different backgrounds and countries — Somalia, Scotland, Bahamas, Vietnam — with widely different life stories, including war refugees, people who came to the United States for advanced education, and those who were visiting years ago and fell in love with an American.

“I feel now the United States are my home. This is where I see my future,” said Paula Boel, an economics professor at Bowdoin College who is originally from Italy. She came to the United States in 2000 to earn her Ph.D. at Purdue University. “I would like to be able to participate in all aspects of the country.”

Muktar Hersi’s path was different. His family fled war in northern Somalia when he was 15, walking through Ethiopia to the Somali capital, Mogadishu, only to have the central government collapse into civil war. They fled south to Kenya and 20 years ago emigrated to the United States, settling first in Atlanta, then moving to Maine in 2001.

For him, the United States is a land of freedom.

“You have the same rights whether you get here yesterday or came here a hundred years ago,” Hersi said. “I work. I have a family. I have a house. I have a big semi-truck. … My daughter is going to Georgetown.

“Whatever you want to do in America, you will be able to find it.”

For many of those who navigated the minefields of violence and hardship to arrive at this point, the freedom to be who they are is what means the most in their new life.

Oday Saood of South Portland had been kidnapped twice in Iraq — the first time just himself, then a second time with his family. They were singled out because they were an ethnic minority.

“In Maine, we are more safe,” said Saood, who manages a business working with rental car agencies. In Iraq, he owned a fashion shop before he and his family emigrated to Turkey in 2006.

His wife, Alaa Jasem, works in the multilingual program in the Portland school system and was an English teacher in Iraq, where they were not able to live without interference from people who resented their ethnic background, she said.

“Here you can tell there’s nothing different between you and another citizen and everybody respects the others,” she said.

The keynote speaker at Friday’s ceremony was Tim Wilson, special adviser to Seeds of Peace, a youth leadership organization that brings together young people from countries where there is animosity between different ethnicities and helps them learn to relate to each other as people. Acknowledging the many paths that have led people to become Americans, Wilson, who is of African-American heritage, said he is descended from someone brought to the United States against his will.

“The world is not perfect. The U.S. is not perfect,” Wilson said, “but we can work hard to make it the best place it can be.”

People do not erase their pasts when they become citizens, said Andjelko Napijalo, a Portland police officer who watched as his parents were naturalized Friday. Like him, they had been citizens of the former Yugoslavia when it disintegrated into civil war. As animosities erupted, they left behind their homes and everything they had spent a lifetime building.

“They came to this country with 300 bucks in their pocket,” he said, then immediately started rebuilding their lives.

Napijalo is proud of his heritage and proud of the resilience his aprents showed in relocating and learning a new language. For them, he said, the citizenship ceremony was an affirmation that their English skills had progressed to where they could join American society in full measure.

The collection of immigrants all raised their right hands and took the oath of allegiance. The audience, made up of Portland High students and the new citizens’ family members, erupted into applause.

As the ceremony closed to more applause, the naturalized Americans waved small American flags and posed for pictures with their citizenship certificates.

The ceremony was emotional, and not just for them.

“I had tears in my eyes,” said Portland High School Principal Deborah Migneault, a former social studies teacher whose French-Canadian ancestors moved to Maine. The ceremony was a powerful reminder of how fortunate Americans are and how many take that for granted, she said.

Sheila Casey wiped away tears after the ceremony. Clutching a bouquet of red and yellow tulips, she explained how she came here from Scotland 47 years ago and met her husband. She now has two sons and three grandchildren.

“My family is American. My home is here now,” she said of her decision to become a U.S. citizen.

Her emotion was focused more on the people who became citizens alongside her, the fabric of America being woven in front of her eyes, “people who have gone through a lot to get here. I have had it easy.”

One of those people was Mufolo Thomas, who in 1997 was urged to flee from his classroom in the Democratic Republic of Congo without even grabbing his schoolbooks as the civil war erupted. He was lucky. Some classmates went home and their parents were already gone.

His family left on foot.

“We walked and walked, days and days — weeks, months, a year,” he recalled. “I was terrified. Sometimes we had encounters with the soldiers, the rebels.”

When he was 7 or 8 years old, they moved to a refugee camp in Zambia where he lived for nine years. After immigrating, they lived in Atlanta. He and his siblings had to get themselves ready for school because their parents worked through the night and weren’t home in the morning.

He graduated from Lewiston High School in 2009, though he admits his imperfect English made it difficult.

Thomas said citizenship is like a bell ringing in his head, proclaiming freedom.

“I don’t have to run from anybody else,” he said. “It means so much to me. I wouldn’t want to be a citizen of any other country.”

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.