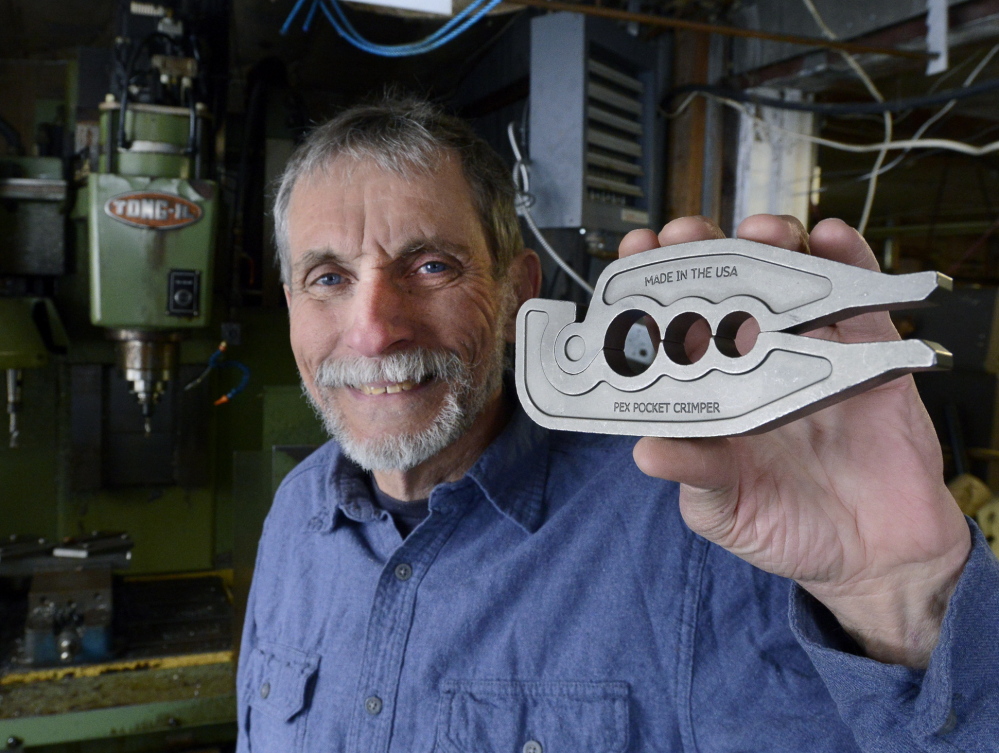

When a plumbing supply company accused Dan Kidd of infringing on one of its patents with a novel crimping tool he had created to secure plastic tubing, Kidd turned to a free University of Maine School of Law program that helps inventors protect their intellectual property.

With help from the school’s Maine Patent Program, which provides free legal services to inventors and entrepreneurs, Kidd successfully defended his invention and then filed his own patent. His PEX Pocket Crimper is now sold by national hardware store chains such as Lowe’s and Home Depot. It has made Kidd a wealthy man.

Inventors in Maine who face similar challenges in the future won’t have access to the same services. The law school, which administers the patent program, confirmed this week that it will terminate it at the end of this school year because of insufficient funding.

The loss of the program, which was created by legislation in 1999 and has helped hundreds of entrepreneurs and UMaine faculty members protect their inventions since 2001, will create a void for the state’s entrepreneurs, said advocates for Maine’s startup community.

“It definitely leaves a vacuum,” said Sean Sweeney, a patent attorney and UMaine law school graduate who worked in the patent program as a student. “This was the only source for inventors to get free legal advice regarding the patentability of their inventions.”

Patents represent innovation, and innovation drives economic growth, which is why protecting the intellectual property of creative people should be an important piece of any economic development strategy, say economic analysts. The elimination of the Maine Patent Program is not just a loss for the 100 or so inventors who used it annually. It also could have consequences for Maine’s long-term economic growth.

Don Gooding, executive director of the Maine Center for Entrepreneurial Development, said he will be sad to see the program go.

“Maine has a lot of free and almost-free resources for entrepreneurs, and this has been one of those we appropriately could brag about,” Gooding said.

Without the free legal advice, Kidd said, he would have been “dead in the water” when he received the legal challenger’s cease-and-desist letter. At the time, he couldn’t afford a lawyer. He tried to go it alone but quickly determined that he needed expert help.

“If I didn’t have the patent program, I would have had to give up on the whole thing,” Kidd said. “It was very discouraging.”

PROGRAM’S FUNDING WAS ERODING

The Maine Patent Program is yet another victim of budget cuts in the University of Maine System, which includes the law school in Portland. The system is trying to offset a deficit of $36 million caused by flat state funding and two years of tuition freezes.

“The entire University of Maine System is facing enormous financial pressures, and we are not immune,” Peter Pitegoff, the dean of the law school, said in a written statement. “Due to budget constraints, our capacity to meet the demand for patent legal advice has diminished. Unfortunately, we are no longer able to support the program.”

On average, the program has provided free legal services to about 100 Maine inventors each year, although that number has dropped recently, said Trevor Maxwell, the law school’s director of communications.

Beyond helping inventors understand whether their inventions can be patented, the program’s staff in some cases files provisional patent applications on behalf of clients and works closely with the university system to provide intellectual-property counsel to staff and faculty members who develop inventions as part of their research.

The program’s demise is not a complete surprise to those familiar with Maine’s innovation community. The law school has been reducing its funding and staff for the past several years.

In the 2011 fiscal year, the program had the equivalent of 3¼ full-time staff members, one contractor and an annual budget of $376,571. In this fiscal year, the staff is down to two people – a director and an administrative specialist – and a budget of $241,572. The law school’s overall budget for 2014-15 is still under review and details are not yet available, Maxwell said.

Bob Martin, president of the Maine Technology Institute, said the program’s budget cuts have not gone unnoticed by entrepreneurs, and its demise is something of a “self-fulfilling prophecy.” As the program reduced its staff and decreased its capacity to help entrepreneurs, he said, those entrepreneurs began to look elsewhere or gave up.

There is nowhere else to get the same free resources that the program has provided, but entrepreneurs said that will have to change.

“For entrepreneurs, there’s a great need to understand the patent process,” Martin said. “It’s a daunting process, but patents are necessary, and the path to receive one can be long and expensive, so the more advice and counsel entrepreneurs have in the very beginning is critical to be able to navigate that process.”

PATENTS CAN LEAD TO TAX REVENUE

Martin and Gooding said their organizations, which partner in many efforts, will begin exploring ways to fill the void left by the Maine Patent Program.

Martin compared the program to a library book.

“It’s there if you need it, and you go hunt it out. If you don’t need it, it sits there until you do,” he said. “We have a need for those kinds of resources, and that was one of them. The challenge at (the Maine Technology Institute) is to find out what we can do to fill that gap.”

Patents are especially important to an organization like the institute, which invests in high-tech companies that often must patent their intellectual property to be successful.

Patents, and the number granted to inventors and companies, are often used to gauge the amount of innovation happening in a state’s business community. Entrepreneurial indices and other reports that claim to rank a region’s level of entrepreneurship often use the number of patents.

Maine, which received 234 patents for inventions in 2013, according to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, has historically not done well in such rankings, said Martin.

“When ranked in terms of entrepreneurial environment, we rank low because patents are a drag,” Martin said. “But while they’re a measure of innovation activity, they’re also a proxy for sales and revenue. States that rank high in innovation indices tend to also rank high in terms of sales and revenue, profitability and number of new ventures.”

Kidd points to himself as an example of how the state’s upfront investment in patent assistance can pay dividends. He called it “counterproductive” to kill the program, noting that he has paid “a tremendous amount of taxes” to the state on the income his tool has generated.

“So they got their share,” Kidd said. “I don’t think that’s something they think about … when they decide to shut down a program.”

CAN ANOTHER GROUP ASSUME ROLE?

The Brookings Institution completed a report last year that sought to determine how patents fit into the larger economic development picture. One finding was that inventions, which are represented by patents, are a major driver of long-term regional economic performance, and that patenting is associated with growth in productivity, lower unemployment rates and the creation of more publicly traded companies.

“A low-patenting metro area could gain $4,300 more per worker over a decade’s time if it became a high-patenting metro area,” the report says.

That conclusion mirrors the thinking behind the Legislature’s creation of the Maine Patent Program 15 years ago.

Jake Ward, the University of Maine’s vice president of innovation and economic development, was an advocate for the program’s creation. In 1998, the Legislature created the Joint Select Committee for Research and Development, which made recommendations that included the creation of a program to help inventors and other entrepreneurs navigate the process of protecting their intellectual property. During the same time, the Legislature created the Maine Technology Institute and the state’s business incubator system.

In retrospect, Ward said, the UMaine School of Law probably was not the best organization to house the program. In cash-strapped times, organizations must focus on their core constituency, which for the law school doesn’t include inventors and entrepreneurs, he said.

In his statement, Dean Pitegoff said, “Our top priorities are keeping tuition as low as possible, providing student scholarships, and recruiting and retaining top-notch faculty.”

Given that fact, Ward said he isn’t surprised that the program would be cut when the law school had to make tough budget decisions. Although he’s not happy about it, he does see an opportunity for other organizations, like the Maine Technology Institute and the Maine Center for Entrepreneurial Development, to fill the hole.

Kidd, who now holds a total of three patents, said he hopes the state or another organization will keep the patent program alive.

“It changed my life, really,” he said. “I’m really sorry to hear it’s getting axed. It’s a big loss for the entire community.”

Whit Richardson can be contacted at 791-6463 or at:

wrichardson@pressherald.com

Twitter: @whit_richardson

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.