The violin crashed to the floor with a sickening thud.

Mark O’Connor knew right away the damage was severe, and it left him numb with grief. Since O’Connor first pulled a bow across its strings when the varnish was barely dry, the Maine-made violin has been an extension of his being.

Its personality reminded him of his teacher, the great jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Within a few years, O’Connor was playing it exclusively, setting aside his beloved 1830 J.B. Vuillaume instrument for this handsome $15,000 violin, made with Maine maple and spruce by Jonathan Cooper of North Gorham.

And there it sat, after a microphone cord had snagged and pulled the instrument off a table, shattered on the floor backstage at the Orpheum Theater in Sioux Falls, S.D., where O’Connor was about to play a concert with the Augustana Symphony.

His worst fears were realized when he picked up the Cooper: a deep, long crack along the top and a smaller one along the rib, as well as a split on the bottom.

His mind racing, the musician had no time to contemplate the horror. Anguished and heartbroken, he placed the busted violin in its case, allowing no one to see it.

He had a concert to play. To make matters more urgent, it was being recorded for public radio.

O’Connor, a Grammy Award-winning musician known in classical, folk and jazz circles for his steadfast dedication to American music of all kinds, performed the concerto with an instrument borrowed from the orchestra’s concertmaster, but he couldn’t shake the broken violin from his mind.

“I feel like I went through a million emotions within that hour on stage immediately after she fell to her temporary silence,” O’Connor later told his Facebook friends. “I don’t know why my head didn’t just explode while I was on stage, it was runnin’ so fast – mostly trying to find all of the sounds I could on a strange violin I had not held in my hand until five minutes before.”

That’s not an easy thing to do. The relationship between a musician and his instrument runs soul deep. “The Cooper was the instrument that I practiced, nurtured, babied (and) willed, and with it at my chin discovered all of these new secrets for this music together,” O’Connor wrote in an email to the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

On stage in South Dakota, he put his emotions aside, mustered the skills and showmanship that make him a world-class performer, and delivered a concert that was rewarded with a warm standing ovation. He did his best, and no one in the hall, save for the sound technicians, the concertmaster and a few others, knew he was playing on an unfamiliar violin.

O’Connor did not open the case to take full stock of his fractured instrument until he returned to the privacy of his hotel room later that night. When he did, he discovered an additional crack.

The first contact he made was with his old friend Cooper, who carved the instrument a dozen years ago. Could he fix it, O’Connor asked.

The two men traded texts and emails. During a time of crisis, Cooper was a voice of calm.

“Something like this is very traumatic for a musician,” Cooper said later. “The instrument becomes a part of you. It’s his voice.”

On Tuesday, just four days after the accident, the broken violin was resting on the workbench in Portland on which it was created. Cooper owns Acoustic Artisans, a workshop, gallery and performance space in the Hay Building in downtown Portland.

He cleared his schedule for the week so he could give his full attention to O’Connor’s violin.

The damage was bad, Cooper agreed. But probably not as bad as O’Connor feared. Plus, he had fixed violins before, and this violin he knew intimately.

“It’s my work,” Cooper said. “I know what I did. I know the theory behind it. It’s easier when it’s the same hands.”

Cooper has made more than 200 instruments, mostly violins. O’Connor, a multiple Grammy Award winner and 10-time national fiddle, guitar and mandolin champion, is among the most accomplished of Cooper’s clients. Another is Michael Doucet of the Cajun band Beausoleil.

O’Connor bought this violin from Cooper after a mutual friend from Maine introduced the two men. Cooper showed up at one of O’Connor’s music camps in San Diego with the violin in hand, one of a larger group of instruments that he was showing.

“He picked it up, played it for an hour without stopping and bought it,” Cooper said.

At first, the Cooper became O’Connor’s trusty second violin to his Vuillaume, which was the instrument he used to record his Grammy-winning CD with Yo-Yo Ma and Edgar Meyer, “Appalachian Journey.” He used the Cooper for playing what he called “cross-tuned” pieces, and if he needed to plug in and play electric, he had a bridge pickup on it ready to go.

After eight years of playing the Cooper, O’Connor felt it had overtaken the centuries-old Vuillaume.

As he was preparing to premiere “The Improvised Violin Concerto” at Boston Symphony Hall in 2010, O’Connor made the switch.

“As a professional, these decisions don’t come lightly,” he said in an email. “I was moving from truly one of the greatest instruments I had ever played or heard … to a new violin that had fully acquired the qualities that I knew it could embrace when I first picked it up that day in 2002.”

In time, the Cooper violin developed to be just a little bit better than the Vuillaume, he said. He put the Vuillaume away, to learn to more fully play his new primary instrument.

“The psychology behind mastering instruments can be a bit individual and I take it very seriously,” O’Connor said.

Cooper, 63, appreciates the praise. “It’s gratifying to know your work can be up there with these other guys,” he said.

As Cooper examined the broken violin in his workshop, he guessed that the instrument had fallen on its back end where the saddle and chin piece attach. The impact reverberated most of the length of the 14-inch body, causing multiple fractures.

With an instrument this young, there was less dirt and grime to contend with and fewer impediments that stand in the way of a clean fix. That meant the cracks could be filled with Cooper’s homemade hide glue, and the wood pulled back together precisely as it was before the accident. Cooper even had the same varnish that he used when he built it, so the violin would look identical after the fixes, he said.

Cooper’s workshop is light and orderly. A watercolor painting of a monarch butterfly, painted by Cooper’s mother, hangs over his workbench. A few dozen tools rest on a custom-made tool rack. The sound of traffic on Congress Street passes just below his second-floor windows. A fire truck’s siren occasionally muffles the sound of a fiddler practicing in the next room.

Working by hand and with a small complement of tools, Cooper began by disassembling the violin.

He unhooked the strings and removed the pegs, bridge, end pin and tailpiece. Using a short-blade knife to remove the glue, Cooper worked his way around the edge of the violin, and after 20 minutes or so popped off the broken top, which is a fraction of an inch thick and made of spruce. Most of the rest of the violin is maple.

With the instrument opened up, he removed its guts: the bass bar, a thin piece of spruce that runs along most of the spine of the instrument; and the sound post, a thin dowel housed between the top and bottom of the violin and held in place by the tension of the wood.

With the instrument in two halves and the precision of an artisan who has worked 30 years at his trade, Cooper began the meticulous work of mending the cracks from the inside out.

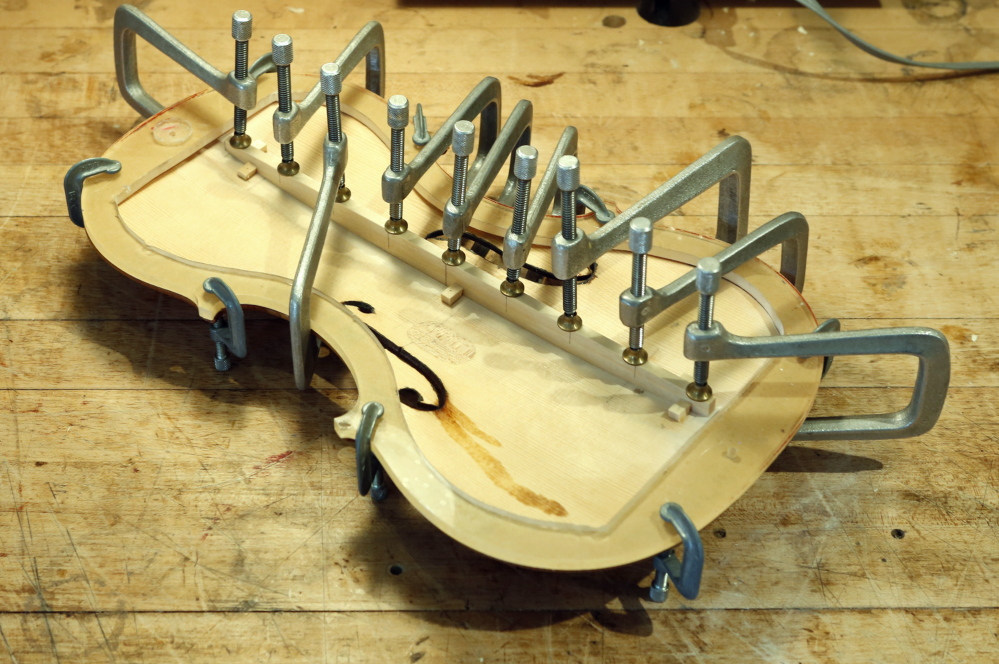

A finished violin, he said, “is fine pieces under tension.” On Tuesday, with the top turned upside down and resting in a frame, Cooper applied glue to the big fissure that ran nearly all of the body’s 14 inches. He held it together with eight high-tension clamps. He left it to set for a day.

He repeated that process with each fracture – glue, clamp, set – until all of the cracks were fused. Then he began reassembling the violin.

First, he addressed the bass bar, which is attached lengthwise along the inside top of the violin. The bar plays a key role in shaping the instrument’s sound. The large crack on the top of the violin ran along the bass bar, so Cooper had to remove it to fix the break.

Not much has changed in the past few hundred years of violin making, Cooper said. But makers engage in ongoing debates about bass bars. Along with the sound post, its placement and design influence the timbre of the instrument and give character to the violin’s sound.

Much would depend on Cooper fashioning a bass bar that replicated the one he removed. He glued and clamped it in place on Thursday, using the original as a guide, then shaped it with a finger plane on Friday. Spruce shavings piled at his feet.

His last act before gluing the top back in place was affixing a series of small wooden cleats along the major fracture line, to give the violin extra sturdiness. It would be as strong in its repair as it was when it was built, he said.

His work completed Saturday evening, Cooper pulled a bow across the strings. The violin sprang to life anew, sending a beautiful song into the spring evening air. Cooper said he thought the violin sounded better now than before, and he felt certain O’Connor would agree.

Cooper planned to get the restored violin to O’Connor at his New York home early this week.

The final test, Cooper knows, will come when the master picks it up and plays it himself. The relationship between a musician and his instruments is personal. It’s in the fingers, the hands, the mind and the soul.

Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.