In the spring of 1977 in Rockland, Mass., 12-year-old Doris Dickson befriended her new next-door neighbor, a high school junior named Gary Irving.

He was four years older than she, but the two connected over music and dancing. They spent most days after school in Irving’s attic talking about life and relationships and listening to the sounds of KC and the Sunshine Band while a disco ball spun overhead.

By the following spring, though, Irving had changed. He became moody, easily agitated.

“I don’t know what happened,” said Dickson, now 48. “He just kind of snapped.”

A few months later, her one-time friend was arrested on suspicion of raping three teenage girls at knifepoint in separate incidents. He was convicted the following June, but before he was sentenced, a judge released Irving into the custody of his parents for a few days. It was a courtesy to a frightened young man who hadn’t been in any trouble before but now faced a lengthy prison sentence.

Irving never went to jail. Instead, he vanished.

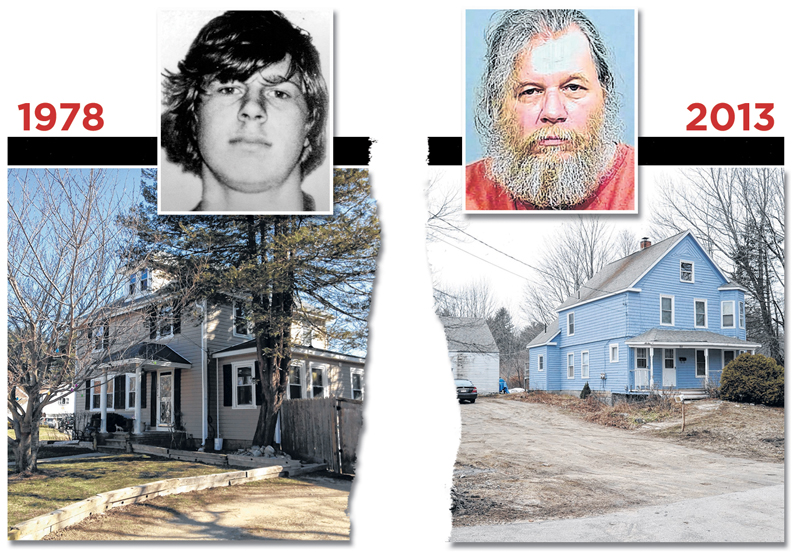

For almost 34 years, he eluded police. He moved to Gorham, Maine, less than 150 miles from his hometown. He got married and had two children.

Police finally tracked down the fugitive on March 27.

Irving has been held without bail since his arrest. His long-awaited sentencing is set for May 23.

Neither Irving’s family in Massachusetts nor his family here in Maine has responded to multiple requests to be interviewed for this story. Detectives in Massachusetts have shared few details about what they have learned about Irving’s life.

However, numerous interviews with childhood friends, neighbors and classmates of Gary Irving, as well as those who knew him in Maine as Greg Irving, paint a picture not of a violent monster but of an introspective, musically gifted boy and, later, an unassuming family man.

Dickson, who hasn’t seen or spoken to Irving in more than three decades but has thought about him often, said she doesn’t know what’s more remarkable: That the quiet boy she knew could inexplicably transform into a serial rapist or that he could seemingly transform back almost as quickly and go on to lead an unremarkable life.

• • • • •

Gary Alan Irving was born Aug. 28, 1960. He grew up on the South Shore, a cluster of seaside villages, working-class suburbs and industrial towns nestled between Boston and Cape Cod.

His father, Carl, was a Vietnam War veteran, a longtime officer in the Army and Air Force and an auxiliary police officer. His mother, Margaret, was a homemaker whom everyone called Peg. In 1964, the Irvings had a second son, Gregory.

The family lived in Rockland, a working-class town of about 15,000 residents, many of whom worked in shoe factories and bakeries that have long since shuttered. On Sundays, they attended the First Congregational Church, where Carl Irving served as a deacon for many years.

Gary Irving had heart surgery at age 12 — a procedure that left two jagged scars on his chest and back but otherwise didn’t disrupt his childhood.

John Albert, 49, was a classmate and friend of Gregory. He knew the Irving family well but has not stayed in touch.

“Carl and Peg, they were wonderful parents. So loving,” said Albert, who now lives in North Carolina.

In 1977, when Gary was a junior, the family moved to Myrtle Street in Rockland, a street not far from the center of town that is lined with modest, two-story homes. The boys could walk to school from there.

Dickson remembers when the Irvings moved in. She was 12 at the time and lived next door.

Although Gregory was closer to her age, Dickson quickly became friends with Gary instead.

They had similar interests. She liked his sandy-colored mop of hair and his slightly pudgy baby face. They never had a romantic relationship, but Dickson said she was flattered that this older boy paid attention to her. He was figuratively and literally the boy next door.

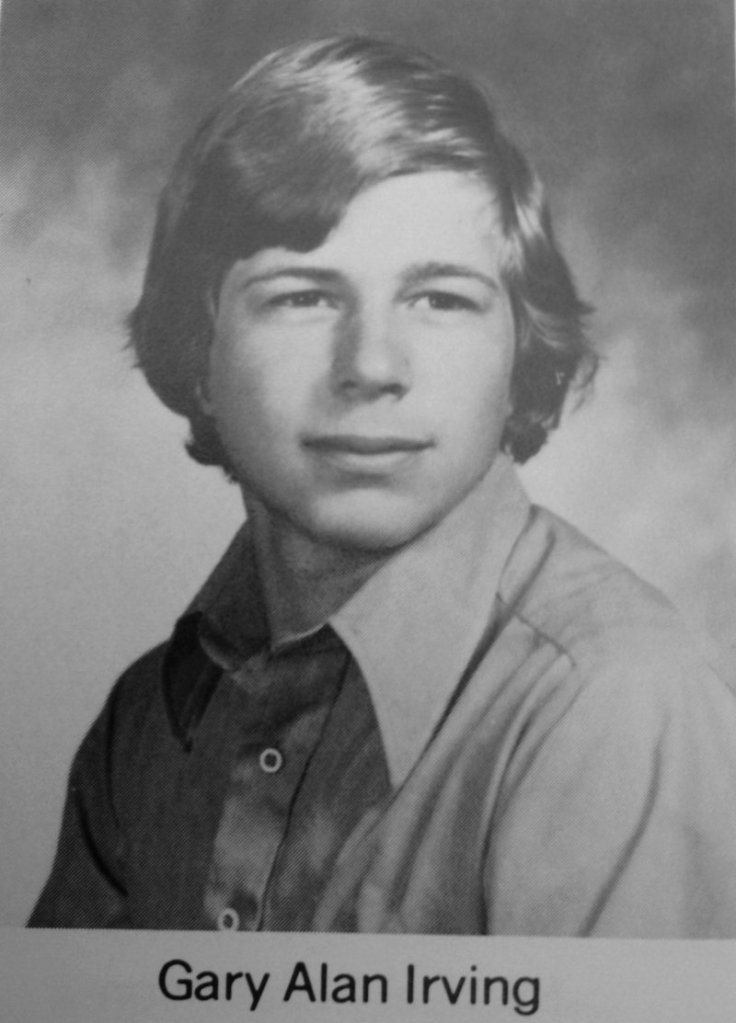

Irving was an accomplished trombone player in the school band and won the school’s Purdue All American music award as a senior. He also was in chorus and performed in high school musicals. He did well academically and told classmates he planned to attend Boston College after he graduated.

If they remember him at all, classmates recall Irving as quiet and unassuming. Not a loner, exactly, but not Mr. Popular either.

“I remember him as this socially awkward kid,” said classmate Steve Waisgerber, Rockland High’s class president in 1978. “He was like a million others.”

• • • • •

Things changed for Gary in 1978, although it’s still a mystery what prompted those changes.

Dickson said her friend shifted from happy-go-lucky to cold and angry.

Waisgerber, who knew Irving well but didn’t socialize with him outside of school, said he doesn’t remember Irving’s mood changing, but he does remember a change that senior year.

“He looked a lot different. Edgier maybe. But part of that might be that he just grew up,” Waisgerber said. “He looked more like a man.”

During his senior year, Irving worked part-time at Hi Lo, a local grocery store, and often went cruising in his parents’ green Pontiac. The car was a source of controversy, Dickson said.

One day in the spring of 1978, Irving drove it through the family’s garage in a fit of rage. Around the same time, Dickson heard from Irving’s brother that Gary went after his mother with a knife inside their home.

She asked her friend about it. He didn’t deny it, but he didn’t want to discuss it, either.

Dickson said she became afraid after that. She told him she didn’t want to see him anymore. When she saw him on the street, she crossed to the other side to avoid him.

She didn’t see or hear about him again until the summer had come and gone.

One day in September 1978, though, her mother sat her down with a copy of the local newspaper. On the front page was Irving’s picture under a headline that contained the word “rape.”

Dickson’s mother asked her if she knew what the word meant.

• • • • •

The first attack was reported to police on July 1, 1978 in Weymouth, a town just to the north of Rockland. An 18-year-old girl was walking home from a friend’s home just before midnight.

The girl passed a green Pontiac parked on the side of the road. When she did, a man jumped out and forced her into the car at knifepoint.

They drove a short distance to a secluded area, where the man sexually assaulted her.

He later dropped her off near her home and left.

Less than two weeks later, in Cohasset, another neighboring town that borders Massachusetts Bay, a young man attacked a 16-year-old girl in similar fashion.

She was riding her bike home trying to make an 11 p.m. curfew when a man driving a green Pontiac knocked her off her bike, forced her into his car with a knife and then raped her repeatedly.

Before the month of July was over, the rapist struck again, this time in the town of Holbrook, just west of Rockland.

The victim was a 16-year-old girl. The suspect was a young man driving a green car and brandishing a knife.

He told one victim that he was being paid to attack women.

The rapes were savage and unsettling for the communities on the South Shore, according to Brian Noonan, who was a patrolman in Cohasset and later became the town’s police chief.

In early September, when Gary Irving was supposed to be starting his first year of college, a young man tried to abduct two teenage girls in Weymouth.

The girls were able to resist. One of them gave police a partial license plate number, which was linked to Irving’s father. The other provided something even more substantial: a blue-and-white graduation tassel.

The Cohasset rape victim had reported seeing a similar tassel hanging from the car’s rearview mirror during the attack.

Police compared the colors to high schools in the area. Rockland High was a match.

Detective Sgt. Jack Rhodes from the Cohasset Police Department found a 1978 yearbook and sat down with one of the victims to go through the faces. She stopped when Irving’s face appeared. That’s him, she said.

The other victims also identified Irving from the yearbook photo. He never concealed his face during the attacks.

On Sept. 6, 1978, Rhodes and another officer went to Rockland to arrest Irving at his home.

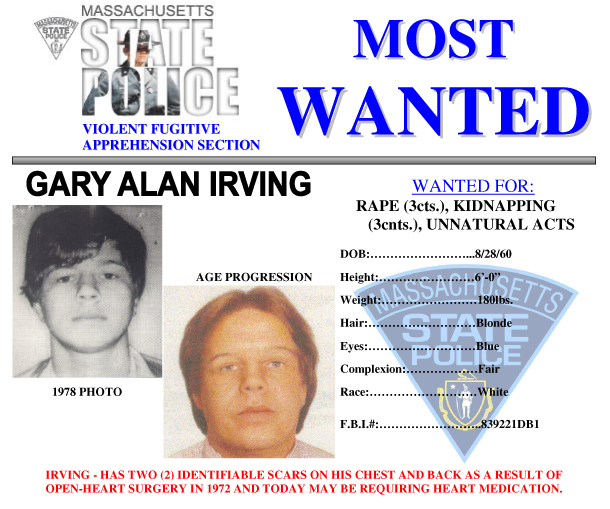

He was charged with kidnapping, rape and committing unnatural acts, which under Massachusetts state law at the time meant either oral or anal sex.

When police took him in, the recent high school graduate said little. Police did ask at one point if they had the wrong guy. Irving just shook his head.

• • • • •

Several months after his arrest, in June 1979, Irving went on trial in Norfolk County Superior Court in Dedham. He had been released on bail since the arrest.

Louis Sabadini, the county prosecutor at the time, was successful in getting a judge to try Irving on all three rapes at the same time.

“He pulled these girls right off the street,” said Sabadini, who has long since retired but still lives on the South Shore. “They were extremely brazen crimes.”

The case was prosecuted before DNA analysis became standard practice in forensic investigations, which meant the prosecution often relied more heavily on the victims’ testimony.

“It was much more difficult to prosecute that type of case then,” Sabadini said.

The three victims did not know each other, but each identified Irving from his yearbook photo. Each described his vehicle.

Sabadini said he doesn’t remember much about the defense but said it was built on a “mistaken identity premise.”

Court documents contain no details about evidence against him at trial but do show that his attorney, Joseph Killion, filed motions to suppress photo identifications the victims made and to suppress statements Irving made to police after his arrest. Killion died two years ago.

After little deliberation, a jury convicted Irving on June 27, 1979.

He faced a lengthy prison sentence — possibly even life — but before that happened the judge did something unusual: He released Irving into his parents’ custody for several days until sentencing — despite Sabadini’s strong objection.

“I argued that he should be held until sentencing,” the former prosecutor said. “I told the judge, ‘This kid isn’t going to show up.’ If it was me, I wouldn’t.”

At the time, the judge said he thought Irving would be secure in his parents’ custody.

He was wrong. Irving disappeared that same day.

In a July 2005 story in the Quincy Patriot-Ledger newspaper, the judge, Robert Prince, then 86, was asked about his decision.

“I extended him a privilege, and he ran out on it,” Prince said. “That was just one of the things a young judge does. I may have made a mistake in doing it, but judges make mistakes.”

Prince died in 2010.

In the same 2005 story, Irving’s lawyer, Killion, said he planned to appeal his client’s conviction and said he liked his chances on appeal.

Killion also said he sensed after the conviction that Irving was terrified of going to prison.

Still, Irving never gave any hints that he planned to flee.

• • • • •

For the first few years, police kept a close eye on Irving’s parents’ home. They checked in regularly with other relatives, both in the United States and Canada, but the scrutiny waned.

“We couldn’t have surveillance on the family 24 hours a day,” said Noonan, the former Cohasset police chief.

The Irvings soon moved out of their home in Rockland and settled in Brockton, a gritty and densely populated city nearby.

John Albert, the childhood friend of Irving’s brother, said the arrest and conviction were hard on the family but they did their best to move on.

“Even after all this happened, they were so nice, always smiling,” said Albert, who lived with the Irvings for a time after the rape conviction. “They were like parents to me. I feel so bad for what they went through.”

Carl and Margaret Irving didn’t have time to dwell on their oldest son and his whereabouts. In 1978, the same year of the rapes, the Irvings had another son who was diagnosed with Down syndrome and needed extra care.

“After a while, it was almost like Gary never existed,” Albert said.

Irving likely would have had some money saved from his part-time job, but no car and no place to live that anyone knew about.

Noonan didn’t work the case initially, but it became his “white whale” over the years. In 1993, when he was named chief, he kept Irving’s file and picture in his office as a reminder.

“His disappearance always dogged me a bit,” he said. “I wanted to see some conclusion for those victims. Nothing ever panned out, though.”

Noonan said police in the late 1970s and early ’80s believed Irving had a connection to Maine. He used to camp there with his family as a child. He said that information was shared with local police in Maine but nothing came of it.

• • • • •

Three years after Gary Irving disappeared from Massachusetts, a man named Greg Irving surfaced in Maine.

He was just 22 years old when he married a woman named Bonnie Messenger, who grew up in Gorham. A few years later, the couple started a family. They had a son, Bryan, and daughter, Jessica.

By all accounts, Irving eased into a normal, quiet life. He registered to vote in 1984. He was called for jury duty. He got a job at a local bank and then at National Telephone & Technology in Scarborough, where he installed phone lines and systems for businesses in southern Maine.

A co-worker at the communications company who asked not to be identified said Irving was quiet but hardworking. He didn’t socialize much outside of work. He didn’t drink. The co-worker said Irving had a camp somewhere in Maine that he used to fish and hunt and that a small group of friends sometimes went with him.

Julie Zimont, who worked with Irving at the former Maine Savings Bank for about five years until the bank closed in 1991, said he was widely liked by co-workers.

“He was so normal. We used to say he was one of the good guys,” she said. “I guess he fooled everybody.”

Irving and his family lived on South Street in Gorham, a main drag not far from the center of town and the University of Southern Maine campus.

The two-story home belonged to Messenger’s parents but Bonnie later purchased it alone in 2002, according to town records. Irving’s name is not on the deed.

Before March 27, police visited the Irvings in Gorham only once over the years. In 2006, someone misused the couple’s credit card and they filed a report.

Irving’s wife and children have declined requests to be interviewed.

Matt Mattingly, who runs a bed-and-breakfast on South Street about a quarter-mile from Irving’s home, said he remembers seeing Irving but doesn’t recall speaking to him.

“He lived under the radar perfectly,” Mattingly said. “But this is the type of town where you can do that.”

Employees and townspeople at a number of gathering places in town — bars and restaurants, hardware stores, coffee shops, the Laundromat, the post office — all had the same reaction to Irving’s picture: He looks familiar, but I can’t place him.

• • • • •

Back in Massachusetts, the Irving case started to go cold.

Noonan, the Cohasset police chief, assigned the Irving case to Detective Sgt. Greg Lennon, and in 2002, when Noonan retired, he told Lennon to stay on it.

The Cohasset police file on Gary Irving is about two inches thick, filled with yellowed pages typed on a typewriter. There are handwritten notes and Polaroid photographs, including Irving’s mugshot from his September 1978 arrest.

During a recent interview, Lennon sifted through the pages, re-familiarizing himself with a case he knows well.

Over the years, Irving’s disappearance was featured on nationally syndicated television shows such as “America’s Most Wanted” and “Unsolved Mysteries.” In one show, one of Irving’s victims shared her story, although she appeared only in a silhouette and was not identified.

Every time a new show aired, Lennon said tips would flood in. He checked on all of them.

Waisgerber, who still lives on the South Shore, said police reached out to him a handful of times over the years about Irving.

“They wanted to know if he had ever contacted me,” he said. “He never did.”

Dickson didn’t stop thinking about Irving. She said for a long time she expected to run into him around a corner somewhere.

Fugitives often try to reconnect with family members during life events, such as weddings or funerals. Irving’s father, Carl Irving, died in September 2003. Police kept an eye on the funeral in case the son returned, but he never did.

Irving’s fingerprints from his 1978 arrest have been in a federal database for decades. If he was ever arrested or imprisoned — no matter where — he would have been found out.

The closest Irving came was a parking ticket.

• • • • •

In June 2011, after years of searching, Massachusetts State Police located their most wanted criminal, James “Whitey” Bulger, hiding out in California.

They figured if a man like Bulger could be caught, so could Gary Irving.

Members of the fugitive apprehension division began to dig into the case with a renewed energy. Detective Lt. Michael Farley said Irving had been on their list the longest.

“We basically started from the beginning,” he said.

They met with Dickson, Irving’s childhood friend and neighbor. They met with Cohasset police.

Finally, they got a break.

Although state police have declined to provide specifics, a law enforcement official who spoke on condition of anonymity told the Maine Sunday Telegram that it was a relative of Irving in Massachusetts who told police where he was.

Around 8 p.m. on March 27, Gorham police officer Michael Brown got a call. State troopers from Maine and Massachusetts were preparing to descend on the Irving home on South Street, but they wanted a local officer to knock on the door.

“They gave me a brief description about this guy and what he had done,” Brown said. “It was clear they wanted him. They didn’t even want us to call dispatch about it.”

Irving was inside watching television with his wife. They had just finished baking a cake together for her co-workers. They were getting ready to help put their toddler granddaughter to bed.

The knock turned their quiet, middle-class lives upside down.

Brown told the Irvings he was there to investigate a 911 hang-up call. Once Brown convinced Irving to join him on the porch, several state police troopers from Maine and Massachusetts were waiting. They told the man what really brought them there.

The bearded man standing on the porch matched the description of the suspect police were looking for, but they wanted to be sure. They asked him to lift his shirt so they could see the scars.

By that point, Officer Brown had gone inside to tell Irving’s wife what was happening. The woman looked at her husband, and then at police, with disbelief.

“She was in complete shock,” Brown said. “If she said she knew nothing about her husband’s past, I believe her.”

Officers arrested Irving and took him from his home while his wife stayed behind to ponder the possibility that the man she thought she knew and the life they had built together might all be a mirage.

Some neighbors on South Street watched from their windows with interest. They recognized the man but knew little about him, even though he had lived in town for three decades.

Irving initially told police that they had the wrong man. But during the ride from Gorham to Cumberland County Jail in Portland, he finally broke down and asked: “How did you find me?”

• • • • •

If the first big question is: How did Irving elude police for so long? The second might be: Could an 18-year-old serial rapist have ceased his violent, compulsive behavior without prison holding him back?

“It has always been my concern that there were other victims out there,” said Noonan. “I have a hard time believing he could have just stopped.”

William Marshall, director of Rockwood Psychological Services in Kingston, Ontario, and a national expert on sex offender treatment, said it would be “very unusual for someone who commits crimes like these at age 18 to suddenly abstain from further offenses and to maintain abstinence for 34 years.”

“That’s a truly remarkable example of self-restraint,” Marshall said by email after reading about Irving’s arrest and criminal history. “I cannot believe he did not harbor deviant fantasies about his offenses for at least the next several years.”

Marshall said most rapists burn out by the age of 40, largely because of a natural drop in testosterone.

“Nevertheless, it is quite surprising that he was able to get through those high-risk years between his last known offense at age 18 years,” he said. “But of course we do not know if he was offense-free for those years.”

Maine State Police spokesman Stephen McCausland said detectives are combing through all unsolved sexual assaults in southern Maine to see whether any fit Irving’s profile from the late ’70s. Nothing has turned up yet.

On April 12, after a brief court hearing in Massachusetts, Irving was ordered to submit a DNA sample, which will make it easier for police to link him to any unsolved cases.

• • • • •

Irving’s attorney, Neil Tassel of Boston, spoke to reporters after that April 12 hearing and said he believes that DNA sample could actually help Irving.

Tassel said he’s confident that his client has not committed any crimes since 1978 and said he’s strongly considering appealing the 34-year-old conviction.

“One of the most significant aspects of the case to me is that things were done very different (in 1979),” Tassel said. “These were crimes that were very traumatic; they were terrible attacks that occurred. There is no question that they occurred, and there was a tremendous amount of pressure on authorities to clear those cases.

“But we now know in many other cases that people have been cleared by DNA.”

Tassel agreed with others about the possibility that a serial rapist could stop that impulse cold turkey.

“Crimes of this nature don’t come out of thin air,” he said. “It seems very unlikely to me that a person of his character could have committed these crimes and then suddenly lost any urge to commit these types of crimes.”

One of the pieces that could determine whether the case is retried is the status of the trial transcript from 1979. It’s the only documentation of what happened and will be relied on heavily by the judge for reference.

Tassel said Friday that some pretrial documents have been located and he’s hopeful that the entire trial transcript will be found as well.

• • • • •

Even if he does appeal, Irving faces sentencing first. That date has been set for May 23 in Norfolk County Superior Court in Dedham, Mass.

District Attorney Michael Morrissey has said that Irving will get a fair hearing but also said his office will seek a “significant sentence.”

Sabadini, the former prosecutor, said he expected that some or all of the victims would be present at sentencing, or at the very least would provide victim impact statements that would help the judge determine an appropriate sentencing.

So far, none of the victims has come forward publicly since Irving’s arrest.

Tassel has said that he plans to argue that Irving has lived a crime-free life for 34 years and hopes that counts for something.

For his family in Maine, they face the possibility that Irving, now 52, may not be free again.

David Butler, pastor of the First Parish Congregational Church in Gorham, knew Bonnie Irving’s family well.

“At this point, I think everyone in town is just feeling sympathy for her,” he said.

“She’s a victim of his, too,” added Brown, the local police officer. “Her future. So much of her life is a lie.”

Shawn Moody, a Gorham resident and business owner who also knew Bonnie Irving, agreed that the news of Irving’s capture is devastating for his Maine family, but also, he said, a long time coming for his victims in Massachusetts.

“Could those women ever put this behind them knowing he was out there somewhere?” Moody said.

Others agreed.

“It’s awful on so many levels,” said Waisgerber, Irving’s former classmate. “The wake of destruction that he created. It’s amazing that 34 years went by for this to be resolved.”

Dickson, Irving’s childhood friend and neighbor, said although she was not one of his victims, like them she has been waiting all these years for resolution.

She plans on attending his sentencing but said she wants to visit him in prison after things settle down.

She really only has one question: “I just want to ask, ‘What happened to you?”‘

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.