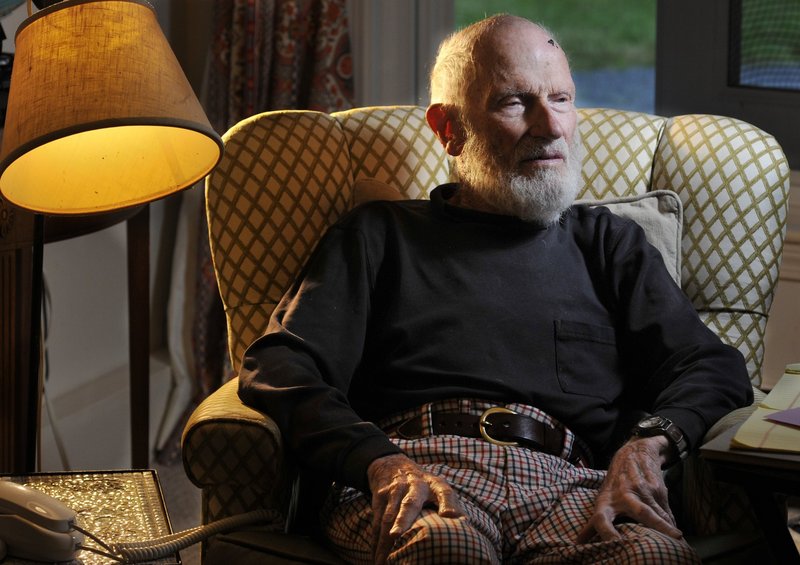

PORTLAND – Norman Morse had hoped to live long enough to see his one-of-a-kind collection of ocean liner memorabilia properly archived and exhibited at the Osher Map Library at the University of Southern Maine.

But Morse, who lived in Falmouth, died last August at the age of 91. In his final days, he was gratified to know that the painstaking work of cataloging and digitizing the 2,800-item collection for online viewing was nearing completion.

On Tuesday, the Norman Morse Ocean Liner Collection will make its debut with an exhibit, curated by Portland maritime historian and author Lincoln Paine, that will run through Aug. 23.

Paine cataloged each item over the last three years, carefully selecting 140 pieces for the exhibit that represent the best of Morse’s rare and comprehensive collection.

It contains slice-of-life ephemera — menus, passenger lists, brochures — from legendary ships such as the Mauretania, the Normandie, the Queen Elizabeth, the Aquitania, the Andrea Doria, the Queen Mary, the Olympic and, of course, the Titanic.

“The exhibit shows the breadth and intelligence of his collection,” said Paine, who interviewed Morse several times. “It’s a unique and amazingly complete collection, largely because of the care and deliberation he took in gathering it.”

Because ocean liners were the only practical mode of travel between the United States and Europe for nearly 100 years, the industry touched every class of people, and the collection reflects the economic, social, historical and artistic changes of several eras.

Gathered over eight decades, starting when Morse was 8 years old, the collection includes floor plans, rate cards, postcards and other items from more than 500 ships that ruled North Atlantic travel from the 1880s through the 1960s.

A 1905 breakfast menu from the Canopic features porridge, fish cakes, deviled turkey legs and grilled mutton chops. A 1925 brochure from the Colombo is decorated with art deco diamond and feather shapes. A 1934 passenger list from the Veendam provides details about the famed Holland-America Line.

The collection shows the transition that passenger ships made from opulent, high-style interiors to the streamlined design of the post-World War II era. It captures the impressive artistry displayed on the ships themselves and on promotional materials used to attract passengers.

Some items feature elaborate graphic arts that were designed long before the advent of computers.

“There’s a brochure from the Normandie with a two-page artist’s rendering of the dining room that’s brilliantly colored and absolutely breathtaking and looks nothing like the interior of a ship,” said Paine.

Back then, that’s what passengers wanted, according to Paine. Dining rooms, beer halls, ballrooms, gymnasiums, barber shops — all were designed to look as they would on land.

“They didn’t want to be reminded that they were 1,500 miles out at sea,” said Paine, who authored “Down East: A Maritime History of Maine,” published in 2000, and “Beyond the Sea: A Maritime History of the World,” to be published in 2013.

When the United States cracked down on immigration in the 1920s, ocean liners were left with a lot of empty cabins. In response, passenger ship companies began promoting tourism to middle- and upper-class Americans who had disposable income and wanted to see the world.

Morse and his family were among those people. He began seriously collecting ocean liner ephemera when he was 14, during his first ocean voyage to visit family in the Netherlands. Passenger ships typically took five or six days to cross the Atlantic.

“That’s when I became really interested in liners,” Morse told Paine. “I went around to steamship company offices in Europe and America and acquired these elaborate publications for no cost.”

Ocean liner travel faded in the 1970s, as faster airline travel to Europe became more prevalent. It rebounded in the 1980s with modern-day cruise ships, which Morse considered a wholly different breed. Ocean liners were a serious mode of transportation, he believed, while cruise ships are viewed as floating hotels and vacation destinations unto themselves.

Morse began seeking a permanent home for his collection in the 1980s, when most of it was stored in a four-drawer filing cabinet. He gave it to the Osher Map Library with an endowment to cover the cost of its preservation and presentation online.

Morse drew headlines last summer when, in a story in the Maine Sunday Telegram, he publicized his desire to end his life because he was in failing health and because he had long supported the individual’s right to medically assisted suicide.

Even as he struggled in the last weeks of his life, Morse wanted to make sure people would be able to enjoy and use his collection for research. Now, they will.

“I think Norman would be very pleased,” Paine said.

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.