Charles Jones sleeps every night in the Oxford Street Shelter’s “medical dorm,” so called because the room is reserved for up to 16 men in poor health.

He’s 55 years old, the average age of the men in the room. They’re allowed inside the shelter a half-hour early, so they can avoid the long lines in sub-freezing temperatures, and they sleep on cots rather than the standard floor mats.

Jones, who first became homeless five years ago after a bank foreclosed on his Belfast farm, suffers from degenerative disc disease and mental health problems that emerged after he lost the farm. He says he’s seeing more and more people in the shelter who, like him, also struggle with health issues.

“It’s the older folks,” he says. “The older generation is growing.”

The demographics at the shelter – increasing numbers of older men with physical and mental health problems – are indicative of a national trend that has implications for public policy, according to Dennis Culhane, a professor of social welfare policy at the University of Pennsylvania who has done extensive research on the demographics of the nation’s homeless population.

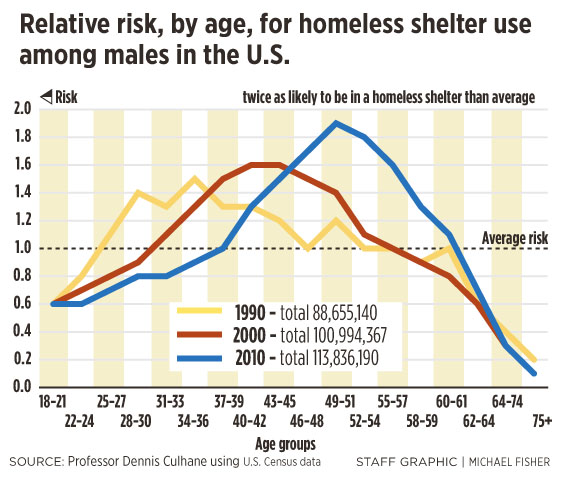

The chronic homeless are aging, he says, but the data does not exactly mirror the overall aging of the nation. Rather, there is one group – men born between 1954 and 1966 – who are nearly twice as likely to stay in a homeless shelter than any other age group.

This group was first identified in the 1990 Census, when they were around age 30. They appeared again in the 2000 Census, when they were around age 40, and again in 2010, when they were around age 50. In each decade, that generation of men had the highest risk of experiencing homelessness.

The shelter staff has noticed the trend as well. While the shelter has always seen a significant number of older male clients over the years, a much larger percentage now are also experiencing acute physical and psychological problems, problems that often come with age, says shelter director Josh O’Brien.

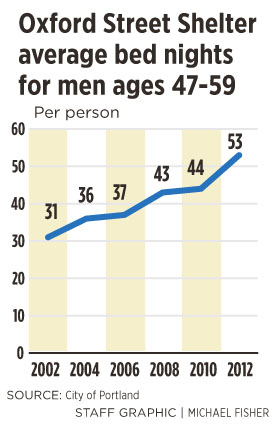

In 2002, men between the ages of 47 and 59 stayed at the shelter an average of 31 nights. In 2012, men in the same age group stayed an average of 53 nights.

They are staying longer because the economy has worsened, budgets for programs aimed at helping the poor have been cut, and many of the men have debilitating health problems that are exacerbated by life on the street, O’Brien says.

“It’s a deadly combination for the men we serve,” he says.

Some of the men who come to the shelter are being discharged directly from hospitals. In the five-month period between June 1 and Nov. 30, 2012, a total of 142 people at the Oxford Street Shelter reported having been discharged from hospitals, including Maine Medical Center and Mercy Hospital in Portland, and Spring Harbor, a psychiatric hospital in Westbrook.

The shelter’s medical dorm didn’t exist a year and a half ago, but is now full. To keep up with demand, O’Brien last week went to Scarborough to buy five more cots at Cabela’s, a hunting supply store. The shelter now has 39 cots set aside for people who are too sick to sleep on floor mats.

Culhane says many of the chronic homeless are young baby boomers who came of age during the back-to-back recessions in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Older baby boomers had taken the best, highest-paying jobs, and housing supply was tightening, he says.

Unable to find work, some of the homeless got involved in the growing underground drug market, in particular crack cocaine. Many ended up in prison, where they became estranged from their families, he says. Others would spend the rest of their lives cycling between unemployment and occasional stints in menial, low-paying jobs.

The combination of substance abuse, loss of family support and economic displacement became defining factors that affected those men the rest of their lives. The impact, Culhane says, has implications both for their own lives and for society.

In an academic paper written this month, Culhane and four of his colleagues contend that the homeless in this age group have been the mainstay of the single adult homeless population since the 1980s and “will soon fade into history but not before medical issues related to aging ensures that they will have one last profound impact on the social welfare system.”

As the men continue to age and suffer poor health, managing their chronic diseases will become increasingly problematic over the next 15 years until the men reach age 64, the average life span of the chronically homeless. While continuing to treat them in homeless shelters is not a realistic solution, there are few other options besides expensive hospital and nursing home care.

No community has yet to figure out a strategy for dealing with this demographic wave, Culhane says.

“Everyone is struggling with this issue,” he says.

The emergency room at Maine Medical Center has seen an increase in the number of homeless patients, and many of them are of the baby boomer generation, says Dr. James Wolak, service chief of psychiatric emergency services at Maine Med.

He says it’s difficult to provide a continuum of services to homeless patients once they leave the emergency room. Their only treatment is often to return to emergency rooms whenever they get sick. It’s an expensive way to treat people.

“They may not be sick enough to require hospitalization but too sick for appropriate care at the shelter,” Wolak says. “There is a lack of something in between.”

In Portland, only two beds are available for homeless people who are recovering from a medical issue and need respite care. The beds are located in a room at the Barron Center, a city-run nursing home.

When the Barron Center program first began in 2000, the men who sought help were typically in their 20s and 30s, says Karen Percival, the center’s administrator. Now she’s seeing men in their late 40s to 60s.

Two beds are not adequate to meet the growing demand, O’Brien says.

He says the Oxford Street Shelter recently housed a man in his 70s who had cancer and had been discharged from a hospital. He had difficulty walking and left behind a pool of blood whenever he was moved from a seat or bed.

The man wasn’t sick enough to qualify for nursing home care, and he also didn’t need to be in a hospital, O’Brien says. If he were in an apartment, he would be able to get some kind of in-home care, such as a visiting nurse. But he wouldn’t qualify for home care under Medicaid while living in a shelter.

Moreover, O’Brien says, a homeless shelter is simply a lousy place to be sick.

“The lack of privacy and comfort is a real struggle,” he says.

The problem is unlikely to find a solution soon. The state is continuing to slash funding for programs that could help the homeless and sick, says Bill Burns, coordinator of Adult Day Shelter Services at the Preble Street Resource Center. He pointed to two cuts in Gov. Paul LePage’s most recent curtailment order: $1.5 million in cuts to a state-funded program that provides mental health services to seniors, and $1.4 million in cuts to the state Office of Aging and Disability Services.

While staff-supported housing would be much cheaper than nursing home care, Burns says, it’s in short supply, and it’s hard to imagine the state creating new housing in the current political climate.

“It doesn’t bode well for those kinds of projects,” he says.

Still, the community needs to establish alternatives to emergency shelters for chronically ill homeless, says Doug Gardner, director of the city’s Health and Human Services Department.

Those alternatives could include assisted-living facilities, group homes, respite housing for homeless people who are discharged from hospitals, and permanent housing with staff support.

In addition, homeless people who are discharged from hospitals need to be processed though a centralized intake center so they can be monitored and provided with the appropriate housing and services, he says.

Gardner says Medicaid funds may become available for some assisted-living programs, and other funding options will become available when the federal Affordable Care Act is fully implemented and everyone, including the homeless, have health insurance.

Gardner plans to begin discussions about the issue with the region’s hospitals, shelter providers, and public safety agencies. Much of the discussion will occur in February and March, and when the City Council’s Public Safety, Health and Human Services Committee takes up the recommendation of the Homeless Prevention Task Force. Among its recommendations: Create a centralized intake center, respite housing and alternatives to shelters.

The current system is fragmented, inefficient and costly, Gardner says, and it fails to deliver needed care.

“It’s an issue we need to formulate a response to,” he says.

Staff Writer Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at

tbell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.