PORTLAND – Maine’s largest school system is at a crossroads.

School officials have been working for the past five years to bring stability and transparency to a system that was so badly managed that administrators at one point didn’t know how many people worked in the district or what they were paid.

With finances now under control, officials are turning their attention to the classroom. Although the system still sends its elite high school graduates to some of the nation’s top colleges, the quality of the district’s academic programs is widely seen as uneven and lacking in rigor.

The school board’s agenda is ambitious. Officials want to increase academic performance so families can be assured that their children can receive a quality education in Portland no matter which school they attend, according to interviews with board members and administration officials.

Board members are particularly focused on retaining the confidence of middle-class families, who have the resources to move to the suburbs or send their children to private schools. The board wants to boost graduation rates, update computer technology, overhaul the city’s elementary facilities and redraw district lines.

The board has yet to decide how to reach its goals, however. Proposals such as aligning class schedules among the high schools or creating specialized academic programs at individual schools are all on the table.

To lead the effort, they’ve hired a new superintendent, Manny Caulk, a former school administrator from Philadelphia.

Many parents are frustrated with the inability of the school board to make the hard decisions that shake up the status quo, and parents are hoping that Caulk will be a strong leader who can make changes, said Kristin Sims-Kastelein, president of the Ocean Avenue Parent Teacher Organization.

Right now, the schools are working well for the top 1 percent of the students who are accepted into the district’s gifted and talented program, while everyone else is stuck on the “middle of the road” track, she said.

“We have supported mediocrity in our school system for far too long,” she said. “There is a lot of hope (that Caulk) can take us to the next level. There is a willingness to be creative and try something new.”

But parents are losing patience, she said, noting that three classmates in her son’s third-grade class last year transferred to private schools.

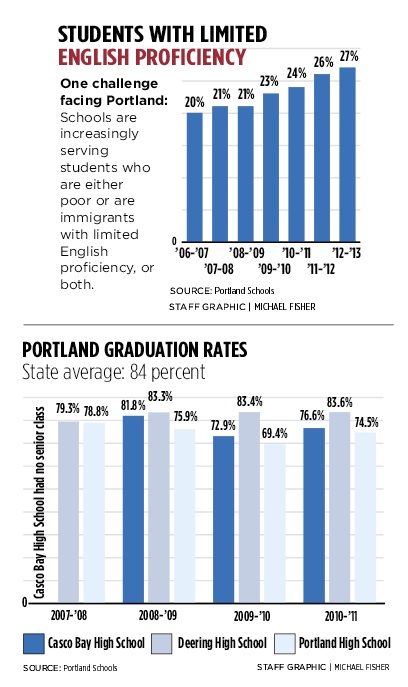

The challenge that Portland officials face, however, is this: Portland schools are increasingly serving students who are either poor or are immigrants with limited English proficiency, or both.

This year, 27 percent of students are classified as having limited English proficiency, an increase of 7 percentage points since the 2006-2007 school year.

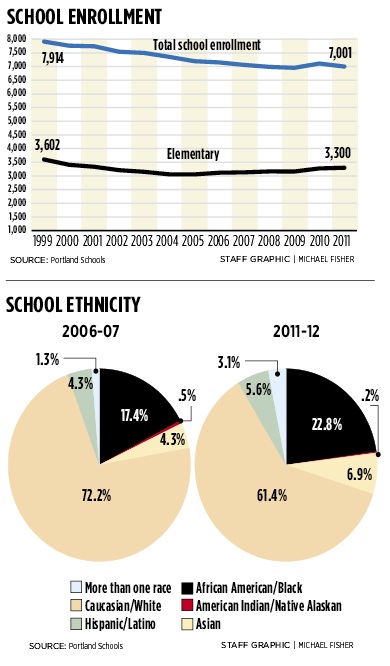

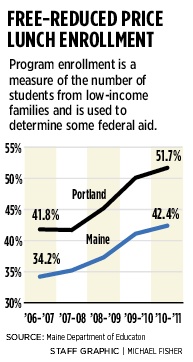

Nearly 52 percent of the district’s 7,000 students qualify for the free and reduced-price lunch program, an increase of 10 percentage points in just six years, in part due to the recession.

The district is below state averages on a number of measures.

The graduation rate at Deering High School is at the state average of 84 percent, but the graduation rate at the city’s other two high schools is below average, with Casco Bay High School at 77 percent and Portland High School at 75 percent.

As a whole, district students perform below the state average on standardized tests in math and slightly below in reading.

Fifty-seven percent of Portland’s elementary and middle school students were proficient or higher in math, 6 percentage points below the state average, according to the scores of last year’s New England Common Assessment Program test. In reading, 69 percent of fifth- and eighth-graders were proficient or higher — 3 points below the state average.

But the scores vary widely school-to-school.

Seventy percent of students at Longfellow Elementary were proficient or higher in math, compared with only 44 percent at the East End Community School and Riverton Elementary School, the city’s lowest-performing schools. Still, both of those schools have shown significant improvement over the past three years.

The Maine High School Assessment test, given to 11th-graders in 2010-2011, found that 40 percent of Portland’s juniors were proficient or higher in math, 9 points lower than the state average. Portland juniors did better in reading, with 48 percent scoring proficient or higher, only 2 points below the state average.

State education officials under Gov. Paul LePage are encouraging parents to compare schools’ test scores, with the belief that fostering competition between school districts and giving parents more choices will improve education. The state is also approving new charter schools, including a charter high school that will open in Portland next year with a focus on math and science.

But no matter how well Portland teachers do their jobs, Portland’s overall test scores will be lower than those in suburban school districts because the tests are given in English — for more than a quarter of the district’s students, English is not their native language, said David Galen, the district’s chief academic officer.

He noted that 2011 graduates from Portland Public Schools are attending 131 colleges and post-secondary programs, including several Ivy League universities.

Still, increasing academic rigor is the cornerstone of the district’s efforts to reform the city’s high schools. For example, the high schools should offer more advanced placement courses, Galen said.

The district is getting some financial help for the reforms. The Nellie Mae Education Foundation has awarded Portland schools $5.1 million over three years. Part of that reform effort includes the creation of a network of community organizations that can provide high school students with educational opportunities outside traditional classrooms and school schedules.

It’s also critical that the district meet the needs of all students, including the district’s best students, said Kate Snyder, who chairs the school board.

“If you lose those kids who are high performers and engaged learners and doing great things, you lose their families, and that’s not good for Portland,” she said. “Diversity comes from people from all different points of the spectrum.”

In its search for a new superintendent, the board only considered finalists from urban school districts with significant populations of minorities and immigrants.

In Philadelphia, where Caulk worked as a top administrator, 56 percent of the city’s 156,000 students were African-American and 18 percent were Hispanic.

Caulk stood out because he was the only candidate who said he would focus on increasing student achievement for all students, not just closing the gap between top students and the poor-performing students, board members said.

So far, Caulk, who started working in Portland on Aug. 20, has done more listening than talking.

Engaging the community is emerging as a top priority for the superintendent. Caulk said in an interview that he wants to reach out to nonprofit groups, faith-based organizations and retirees to get them more involved in the schools.

Earlier in his career when he was a high school principal in Newark, Del., his use of a “Principal for a Day” program gave business leaders and community members a behind-the-scenes look at public schools. Caulk said the program dispelled myths about public school systems and helped him solicit ideas about leadership and innovation.

One business leader decided to send a team of people to help support the school’s efforts to integrate technology in the classroom.

“It was phenomenal. He gave us some outstanding advice and support,” Caulk said. “The more intersections and connections we have with the free exchange of ideas, the better it will be for all of our students.”

There’s another reason for Caulk to increase community engagement: Roughly 80 percent of city residents do not have children in the public school system, and school officials need taxpayers to continue supporting the schools.

The school district spends $12,050 per student annually, nearly $1,000 more than the state average. Most school districts in southern Maine exceed the state average because they pay their teachers more. Portland’s teachers are better-paid than most, with a base salary of $33,669, and a top salary — after acquiring all available professional development credits — of $79,203. Half of the district’s teachers have a master’s degree or higher. The teachers contract calls for a 3 percent raise next year.

In addition, school and city officials hope voters in November 2013 will support a ballot proposal to borrow more than $40 million to build a replacement for Hall Elementary School and renovate four other elementary schools.

School officials say the upgrades would eliminate the inequality that exists between schools and make it easier to draw new district boundaries. Although enrollment districtwide is flat, enrollment at the elementary schools is surging and causing overcrowding in some schools. Elementary school enrollment has increased by about 200 students this year alone.

School officials also plan to spend about $2 million to upgrade computers used by teachers and students. They have yet to decide how to spend the money. But the investment is important to retain students, said Jaimey Caron, a member of the Portland Board of Public Education.

“We have to be serious about competing in technology to make it attractive for middle class families — and all families, really — to make it so they want to send their kids to Portland schools,” he said.

The school district must show parents that their children are prepared to succeed in the workplace or in college at the highest levels after graduating from city schools, said Mayor Michael Brennan, whose two sons graduated from Deering High School and had “no problems” transitioning to Bates College and Bowdoin College.

Still, while many parents would like to send their children to Portland schools, they have legitimate worries about “pockets of unevenness” that exist throughout the system, Brennan said.

He said many parents hope the school board and the new superintendant can raise academic standards throughout the district.

“We need to increase the pockets of excellence and make sure those pockets are extended throughout the system,” he said.

Some parents, though, say the promised reforms will come too late for their children.

Ken Farber, a parent who served on the panel that interviewed the superintendent finalists, calls Caulk a “superstar.”

But Farber, a lawyer, said he transferred his daughter to Cheverus High School this year because she was falling behind in math in the public schools. Last year, as an eighth-grader at King Middle School, he said, she hardly ever had homework, and her math scores on a standardized test dropped significantly, from the 92nd percentile to the 72nd percentile, he said.

While King Middle School does a great job addressing the social issues experienced by children of that age and raising achievement levels of low-performing students, expectations are too low for those who are average or above-average students, he said.

“The kids in the middle and the upper middle are not being pushed as hard as they should be,” he said. “I saw what happened to my daughter in eighth grade. We can’t afford to lose another year.”

Staff Writer Randy Billings contributed to this report.

Staff Writer Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.