FREEPORT — Ten years ago, J.D. Irving Woodlands Division planted only black spruce to replace the trees it harvested on its 1 million acres of Maine forest.

Today, the Canadian company is branching out, planting white pine and other species that can tolerate warmer temperatures.

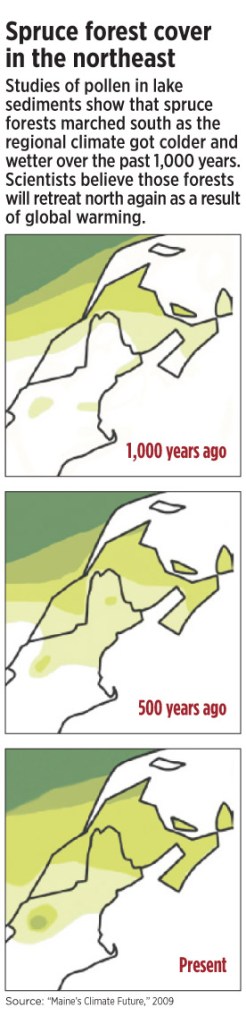

If scientific forecasts for climate change prove correct and the cold-loving black spruce disappears from northern Maine’s forests, the company won’t experience major disruptions in its forestry operations.

And if climate scientists have it all wrong, Irving won’t suffer by having diversified into other species, said Andy Whitman, director of the Manomet Maine Center for Conservation Sciences in Brunswick.

“They are hedging their bets,” he said.

Whitman and others promoted the concept of hedging bets Tuesday during a conference at the Harraseeket Inn that was designed to help conservationists develop strategies to manage and safeguard resources through climate changes caused by global warming from fossil fuels and deforestation.

About 150 people from conservation groups across northern New England attended the event, sponsored by the Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, an environmental research organization based in Plymouth, Mass., with an office in Brunswick.

They were told that climate change is in fact happening in northern New England, and that businesses such as forest companies are already positioning themselves to adapt and even capitalize on the change.

Maine state Climatologist George Jacobson and Hector Galbraith, a leading climate scientist with Manomet, pointed out some of the signs of climate change:

n Lilacs in Vermont bloom two weeks ahead of schedule.

n Southern bird species such as black vultures and the tufted titmouse are moving into the region.

n Lakes in northern New England are ice-free a month longer than they were 30 years ago.

Jacobson said climate change is nothing new; for the past 2.5 million years, there have been ice age cycles roughly every 100,000 years. In the past, plants and animals have adapted. But since the last ice age, the human population has exploded. The consequences for natural adaptation are unclear, said Jacobson. “That means planning for conservation should not be assuming any status quo.” Rather, he said, conservation efforts should be aimed at maximizing biodiversity by keeping large ecosystems intact, to ensure that plants and animals have room to adapt.

Galbraith said climate change is just like any other stress on the environment. Conservationists will need the tools they already have, such as techniques to control invasive species, to manage resources for the impact of climate change.

Galbraith said Manomet is looking for groups in Maine to work with it on demonstration projects for managing climate change, such as a tree species diversification project under way at the Allen-Whitney Memorial Forest in Manchester, owned by the New England Forestry Foundation. Some people at Tuesday’s event said adapting to climate change has been a looming concern for groups that manage conservation lands.

John Berry of Harpswell said the impact of climate change and how to plan for it is definitely a matter of concern for Maine Audubon, for which he is a board member. “Maintaining places so things can adapt, we need to know more about this because we are going to have to live with this,” said Berry.

Staff Writer Beth Quimby can be contacted at 791-6363 or at: bquimby@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.